Summary of this article

Shukla's philosophy of simplicity was unfurled by a language that defied prevalent notions of syntax and narrative.

The author rues that he did not push himself to meet Shukla and presenting his book to him.

Shukla's characters and situations present ways of reading the poet’s persona; a representation of this complex thing called “the human condition”.

They say you must never meet your idols. Eunice De Souza even says it in verse, in one of her poems, where she admits to being “disconcerted sometimes”. The matter of meeting poets is not necessarily as inspiring as it is made out to be – “Best to meet in poems:/ cool speckled shells/ in which one hears/ a sad but distant sea.”

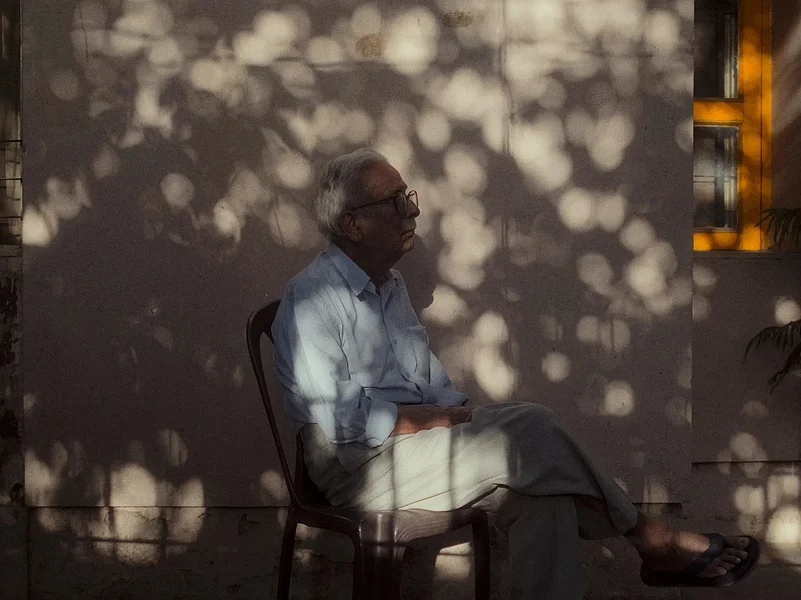

It is true that I’ve never met Vinod Kumar Shukla. It is also true that now, it is too late. I found out about Shuklaji’s death through Instagram, and a message from a dear friend from Chhattisgarh. I closed my eyes, and sighed, when I read about it – there was nothing to it. What can one say? A few months ago, this same friend told me, with a serious face, that “Shuklaji” was unwell, but was out of the woods. He had been in and out of ill health for some time, in the last few weeks, and I wonder if the premonition of his death had come to those who were close to him.

This is not prophecy, but a methodology of attention that emplaces you within the everyday, as a fervent presence that echoes, even in the vacuum of existential dread. Shukla taught this saadgi through the magic of repetition, description, and concerted attention. His philosophy of simplicity was unfurled by a language that defied prevalent notions of syntax and narrative – some critics argued that perhaps popular hindi literature needed to be shaken out of its love for high melodrama, and flourish, the way Shukla’s stories did. But then again, his first collection of poetry’s legendary title isarguably a masterclass in “flourish”. Earlier this year, I referred to that line in a newsletter commentary…

“Sometimes, a poet comes across a line, and realises that they could live forever in that line…”

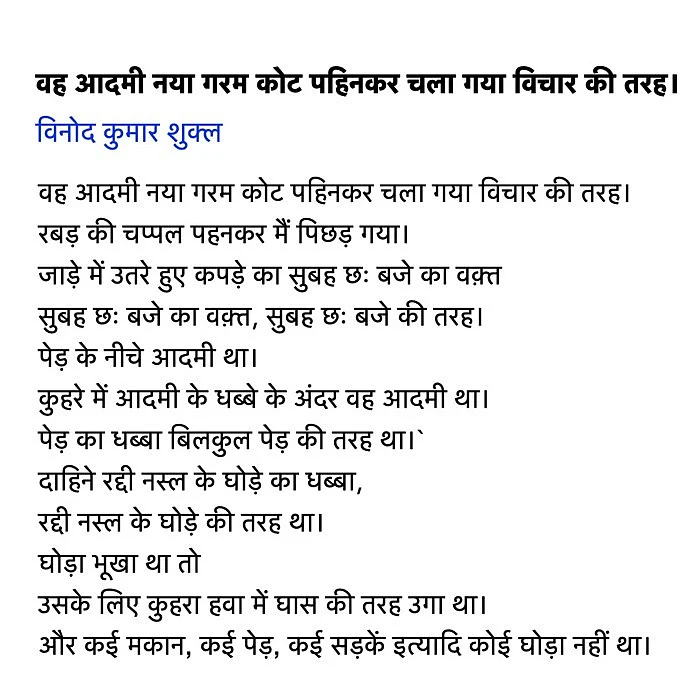

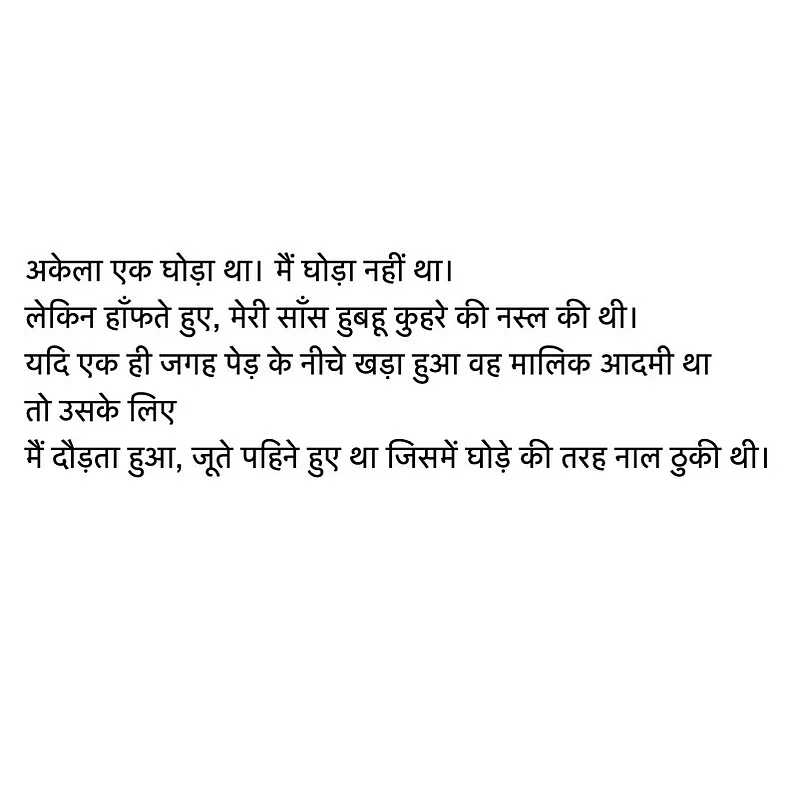

“वह आदमी नया गरम कोट पहिनकर चला गया विचार की तरह।”

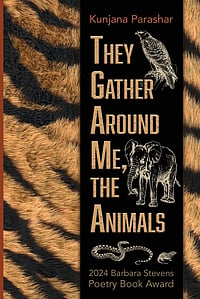

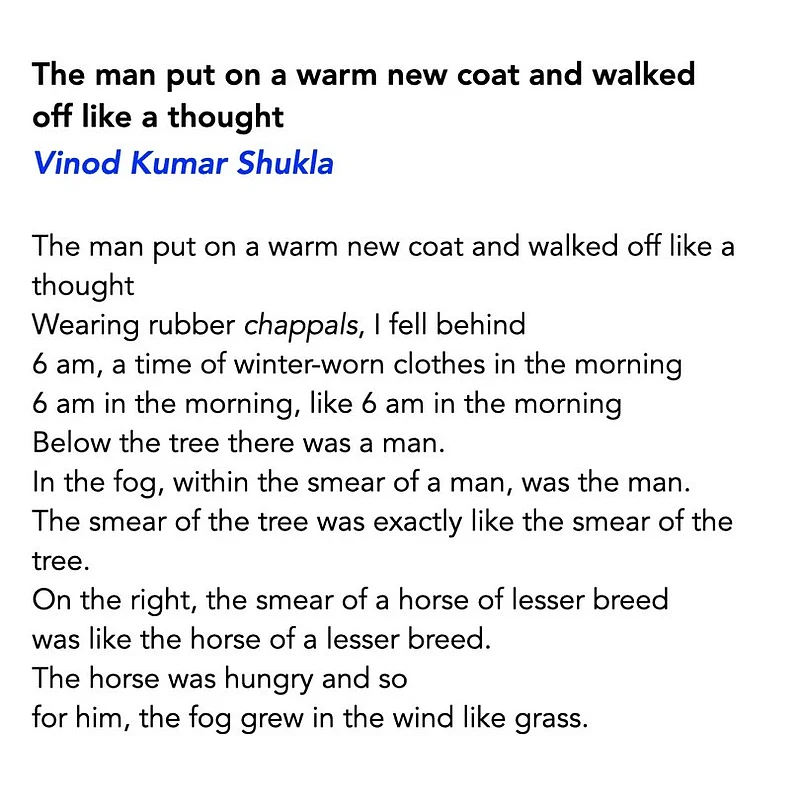

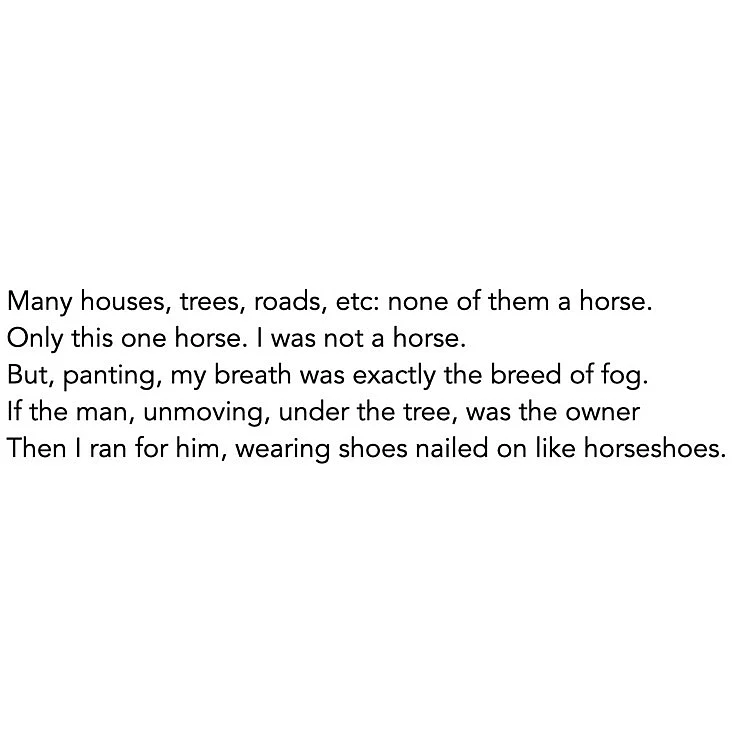

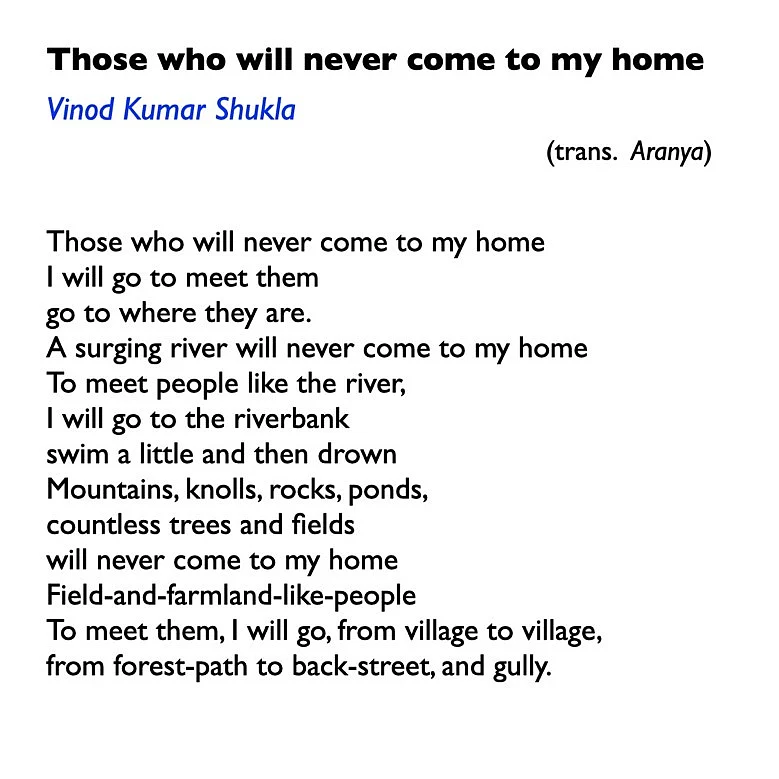

My debut collection of poetry has this line by Shukla as one of its three epigraphs, and the cover, inspired by that poem, is a tribute to his writing. I translated that line as “The man put on a warm new coat and walked off like a thought”. Perhaps one could do away with the “warm”, but then, I wanted the translation to be inadequate – to cleave, and make readers want to reach the original. Wasn’t it Borges who said “the original is unfaithful to the translation”? Thus overturning the conventional relationship between the writer, and the second writer – who translates in the dust conjured up by his leaving. Perhaps translation is a way of reading. Perhaps it will shed some light on this poet-prophet of the ordinary, this quiet writer who wrote stories and poems turning the everyday into surreal truths. I share the complete poem below, along with a translation to give a sense of Shukla’s poetic style.

Chhattisgarh, and the lakes, forests, town and village squares of Chhattisgarh – Dandakaranya, and Abujhmādh (Unkown Hills), Narayanpur and Durg, Borsi, Bhilai, are dear to me. I have spent months in these places, every year for the last few years – during and since the pandemic; so much so that it feels like nanihaal, even more than my actual native place, Mangalore. A whole section of my debut collection is dedicated to that landscape – “the gossip of crickets”. While I deliberately shied away from spending extended periods of time at Raipur, I was intrigued by this writer who had made this “small town” the center of his imaginative metaverse.

I am embarrassed for not pushing myself to meet Shukla, before he left this world; I wished I had presented my book to him – I would often have this vision – that I’d give him my book, and he’d smile at the brashness of young writers – and then embarrassed I’d beat a quick exit, “like a vichār”. I’m sure that would not be how it transpired. But that speculative meeting fit beautifully into Shuklaji’s oeuvreof stories, filled with snippets of everyday existence; snippets that deconstructed an encounter with “boredom”.

A poet meets a poet.

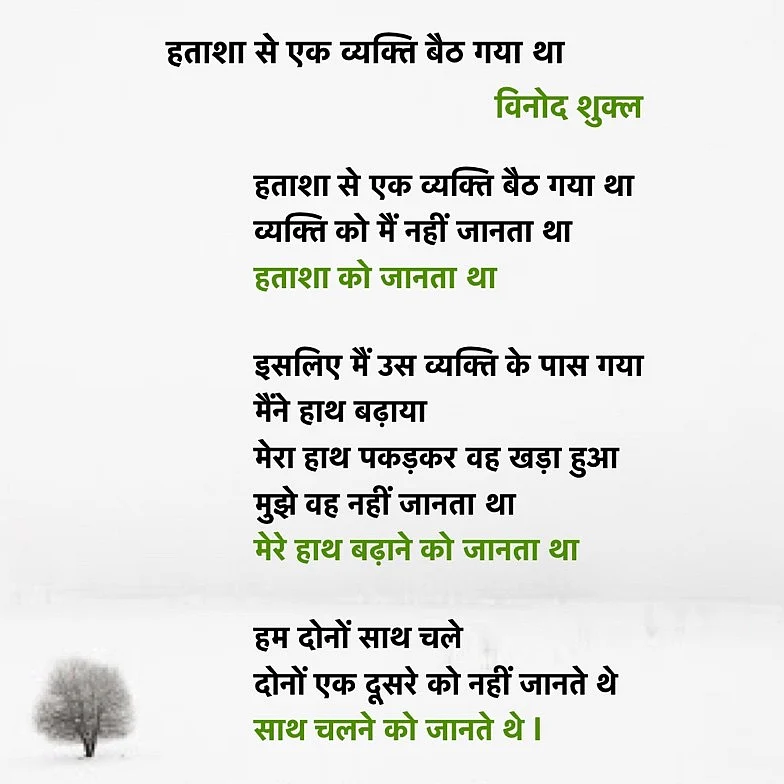

The first time I encountered Shukla’s verse was in a play by Manav Kaul – perhaps it was Ilhām, or perhaps it was Shakkar ke Pānch Dāne. This was the poem, that, many years later, in 2020, I shared in another commentary:

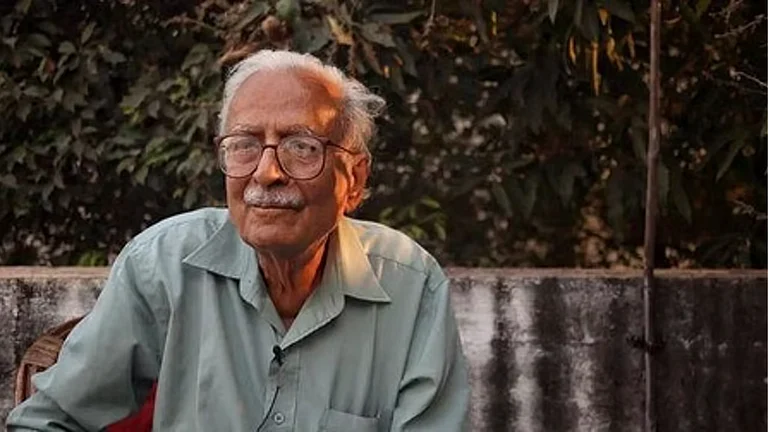

At the time I heard this poem, I did not know the meaning of hatasha, but I guessed that it was “despair”, or a kind of solitude of “frustration” through the context. The poem had a deep impact on me and made me reach his other works including Deewar mein Ek Khidki Rehti Thi (that won him the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1999) and Naukar Ki Kameez (that Mani Kaul adapted into a film). But it was his poetry, always, that left me breathless. Shukla was a teacher in a college of agriculture, but his writing never reeked of the pedantic assurance of “guidance” or the prescriptive certainty of dogma. It was quite the opposite. Shukla’s poems sat in the sleeves of the ordinary, like the persistent breeze that reminds you that it’s there, only by an absence of effervescence.

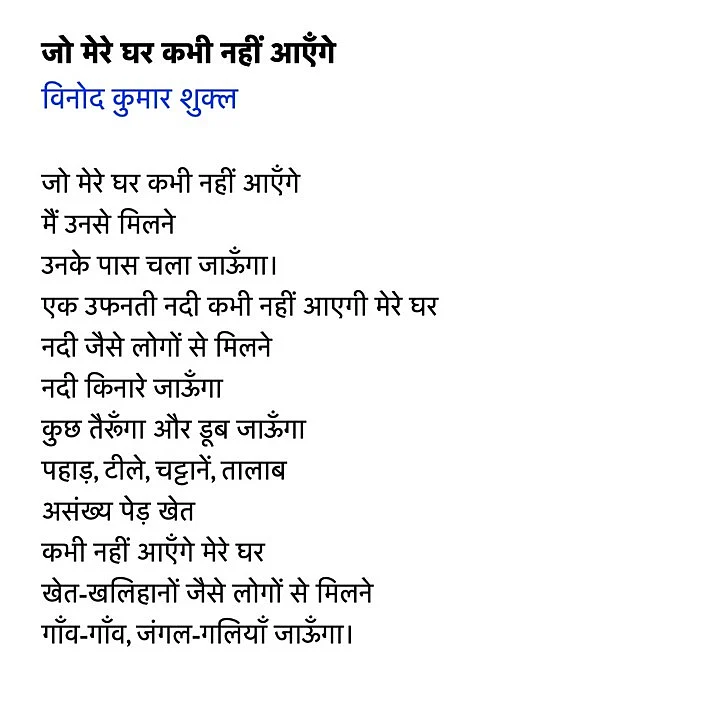

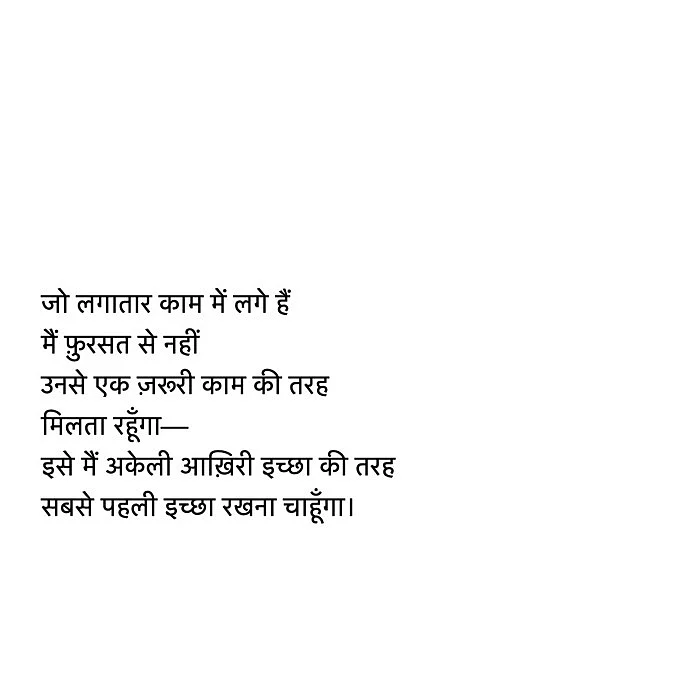

I cannot claim to know Shukla personally, but when I started working on translating Shukla’s first collection of poems, I felt like I understood the man intimately. Doesn’t this happen? Isn’t this why weread? Why we write? To meet another? To encounter in the words of another, the mystery that we have been trying to unfold, ourselves? I am certain that all writing is autobiographical – it is this belief that leads me to believe that sometimes one could form a clearer picture of a poet’s life and faith, through their writings, than their speech and actions. Shukla’s characters, the situations and human conundrums, the characteristically stilted repartee, and internal monologues – are ways of reading the poet’s persona; a particularly clean representation of this complex thing called “the human condition”. Shukla writes about meeting people – even about meeting people who don’t want to meet him!

In the last year, when I spent hours going through Shukla’s poems, preparing a selection for translation, even using some of his poems in my own writing, I did not realise when his words started becoming a part of my everyday. At the onset of winter in Delhi, my friend and I would joke about the various naya garam coats lying in the house. Every time we saw a window in the villages we would chant, like schoolboys – deewar mein ek khidhki rehti thi. Perhaps, it might be considered blasphemy or “reductionist”, but to me, even this kind of engagement is a testament to the superfluous presence of literature, and Shukla’s art, in the everyday of people he never met. This is the way it should be. I am not able to conjure up eloquent assessments of Shukla’s mastery of language, and his tremendous impact on the literary imagination of this subcontinent. He got the prestigious Jnanpeeth Award a few months before his passing, and only last year a beautiful little film was made on him, that draws from the rhythms of his own writing – Chaar Phool Hain Aur Duniya Hain (2024). But I want to let Shukla, the poet, have the last word – tentative, and final.

Absolute in a way that only he could craft.

All poems featured in this essay can be found in Rajkamal Prakashan’s Pratinidhi Kavitaein of Vinod Kumar Shukla.

Aranya is a poet, currently based in Delhi, a place to which he doesn't belong.