Summary of this article

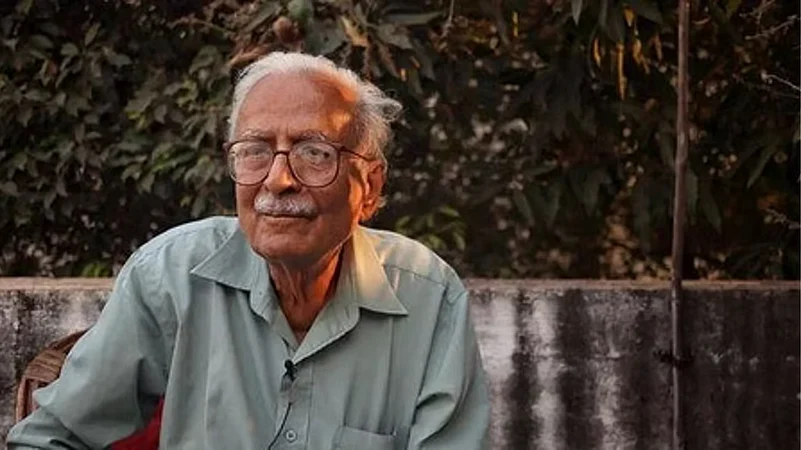

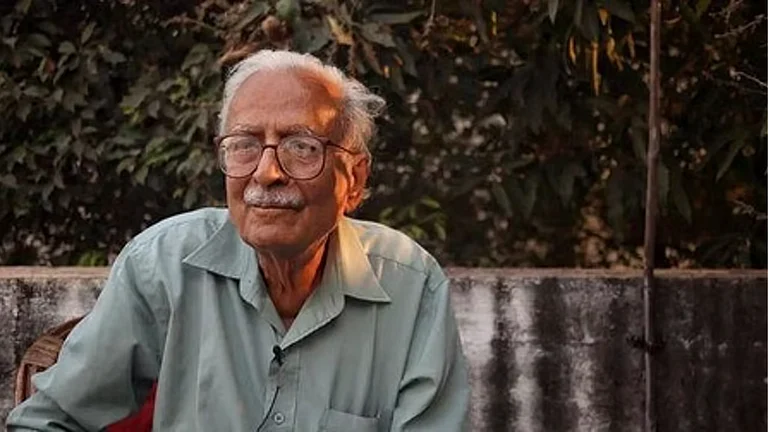

Eminent writer and Jnanpith awardee Vinod Kumar Shukla would have turned 89 on January 1.

His poems have also faced bitter criticism, especially the imagery, metaphors, and symbolism used in his novels.

The writer talks of how Shukla was never a poet of “direct speech”.

On January 1, 2026, Jnanpith awardee Vinod Kumar Shukla would have turned 89, but 9 days earlier, he left this world. In Hindi literature, he was perhaps one of the few people after Agyeya who were famous for their deep lyrical expression in both prose and poetry. Each one of his lyrical expressions was filled with rhythm, irrespective of the work being poetry or a novel. Even in lines expressing resistance, one finds elements of thoughtful rhythm; for example, in his novel “Naukar Ki Kameez”, Vinod Kumar Shukla writes, “Even a man who has been hungry for two days will laugh if he is tickled with intellect. In India, millions of people are victims of this “tickle”." This novel was written in 1979. Today, it has been 48 years since this novel was written, and in today’s world of globalisation, consumerism, and “infotainment”, rarely can anyone find a more intelligent, defiant, and rhythmic sentence than this. The two sentences capture the reality of the whole country.

Vinod Ji was the kind of writer who used to craft the aesthetics of the lives of people who are believed to be average and ordinary. His novel “Deewar Me Ek Khidki Rethi Thi” was awarded the Sahitya Academy Award, and is considered a modern-day classic. The Hindi literary world was astonished when they first witnessed schoolteacher Raghuvar Prasad and his wife, Sonsi, in the remote region of Chhattisgarh. There were no villains or any kind of social struggle in this novel. Through the character of Raghuvar Prasad, Vinod Ji explains that even though the blossoming of flowers may not shut down the slaughterhouses, the very act of this blossoming pitches resistance against atrocities. The secrets of beauty lie in the natural pace of human beings; this “theme” is the fundamental of this novel. The rapid pace of the world has snatched our “present” from us. Vinod Ji repeatedly emphasises the “present”, and even the novel begins with “Today’s morning”. The sun, the moon, the stars, days, nights, even the animals and the birds—he witnessed them all through the lens of “today”; even “the trees visible from the window were trees of today. Amidst the mango trees, there was a neem tree, and that was today’s tree.” Whenever Sonsi saw Raghuvar Prasad, then “Every time she looked at it, she noticed something that she had missed before… She probably realised that she had not seen it (before) when she looked at it first.” For them, every day was a new and fresh day; “the joy of the present was such that the future was left neglected, almost forgotten along the way; by the time you reached it, it felt the poor thing had moved even further away”—one cannot witness this world if one is always in a hurry. Because of these reasons, Marxist critics of Hindi desisted from praising this novel for a long time.

As it happens, Vinod Ji’s poems have also faced bitter criticism, especially the imagery, metaphors, and symbolism used in his novels. But unperturbed by any criticism, Vinod Ji went on to create 10 poetry collections. His first poetry collection, “Lagbhag Jai Hind”, appeared in 1971 and it was at this time that his poetry took a huge leap. Around this time, most of the Hindi poetry was a victim of verbosity, and Vinod Ji emerged with his concise and rhythmic poem, where an ordinary human recounts his mundane experiences and intentions: “In despair, a man sat down. I did not know the man. I knew despair. So, I went to him. I extended my hand towards him. He caught it and stood up. He did not know me. He knew the offering of the hand. We walked away together. Both of us did not know each other. But knew how to walk along.”

In his final days, he started writing poems and stories for children as well. His last poetry collection, “Keval Jadein Hain”, was published in 2025, and contains poetry written by him in the 1960s. These poems do not follow a chronology of a calendar; rather, they narrate discourses that emerged within the slow pace of civilisation. Since the history of poetry across the world is more than two thousand years old, poetry, especially Indian poetry, has given birth to profound skills of expression, and Hindi is no exception to it. Vinod Ji was never a poet of “direct speech”. For instance, regarding “home”, he writes, “Home isn't so much for going as it is for coming,” or “Whoever does not come to meet me in my home, I will go to their home to meet them. Mountains, hills, rocks, ponds, countless trees, and fields will never come to meet me. To meet the fields-like people, I will go from village to village through forests and lanes.” Look at the eagerness to meet here. Good wishes, turning impossible into possible, are abundant. Vinod Ji’s poems used to unravel in layers of meaning. But this isn't ambiguity; the poetry unravels within the symphony of the undertones behind the apparent meanings.

In the last few years, the dispute between Vinod Ji and Hindi publishers came to the fore, through which emerged the issues pertaining to authors’ rights being violated. The issue came to light because of Vinod Kumar Shukla’s case. Meanwhile, a few literary figures on social media criticised Vinod ji, alleging that he never made any memorable intervention in contemporary politics and social issues. Many times, overenthusiastic people such as these forget that in a democratic country, a poet does not carry a gun; they carry words, and those words make their mark when necessary. A depiction of today’s India emerges from the poems of Vinod Kumar Shukla— “With their share of hunger, not everyone receives their share of rice; the roti being baked in the tandoor at the market, is not being baked for everyone to share. The time that is ticking on everyone’s clock – not everyone has a share of that time at this moment.”

Pravin Kumar is a novelist and Associate Professor, Hindi Department, Delhi University