Summary of this article

Absent People, Absent Places maps melancholy through cities, memories, and silences, treating absence not as loss alone but as a generative space where identity, history, and emotion are continuously negotiated.

Drawing on Subramanian’s deep engagement with Bombay’s literary and marginal histories, the collection weaves the intimate with the documented, showing how private griefs are shaped by collective erasures and cultural memory.

Like Hoskote’s Tacet, the poems privilege restraint, pause, and the unsaid, using quiet as a formal and ethical stance to reflect a fractured contemporary self-navigating dislocation and belonging.

Saranya Subramanian’s feisty debut collection of poetry, Absent People, Absent Places, is out in bookstores, and on Amazon, and already, it is creating waves in the literary and cultural establishment.

At the Jaipur Book Mark – a flagship section of the Jaipur Literature Festival – Saranya was part of an eagerly awaited conversation with her literary agent, Jayapriya Vasudevan, and two other acclaimed authors discussing the intricacies of book making, managing expectations, and collaborative work.

Subramanian is the host, and founder, of The Bombay Poetry Crawl, an initiative that brings together the literary arts, the archive, and the everyday in an informed itinerary of “walks” and “crawls” that insert poetry bang into the heart of the everyday. The initiative, covered by The New York Times, lists her work as one of the must-see experiences. Over her many years of engaging with the mythic “milieu” of Bombay Poetry, Saranya, has developed a sensitivity to both place, and persona, that shines through in her diligent research, and her genuine emotional connection and working relationships with writers, activists, and marginalised communities in the city. Now, with the release of her first book, this connection is fortified and deepened.

A Barometer of the Time

In the poem Tacet, that opens his poetry collection, Icelight, the poet Ranjit Hoskote asks at the end, “Of what/ am I the barometer?”. This line came back to me as I was reading Saranya’s poems. I have come to think of the work of this young researcher, literary critic, and impassioned poet, as a ‘barometer’ of the time.

It is difficult to speak, with any self-awareness, of our own “interesting times”. While critics and commentators venture opinions, and ways of thinking about the present, very few can embody, through their practice, a kind of living history of the present. Saranya’s intuitive wonder and terror, her inspirations, and anxieties, form the emotional undercurrent of an outlook that enters this contemporary – this shared time – with a fearless self-consciousness. There is an element of voyeurism, no doubt, that addresses her curations of walks, but it is balanced by the insertion of the reader of poetry, and in the case of her book, the poet, themselves. Her politics shines through, locating identity within practice through collaboration.

We are in an age where the old rules of “spectacle” and “consumption” come crashing down in the debris that stretches between the self, and the world. It is this line that her poetry crosses – with messy panache, and compelling vulnerability. In an intense, but measured epistle to the reader at the beginning of the book, Saranya lays bare this trope: “If absence represents the disintegration of the nation, then presence represents recognising and piecing together the fragments, however fractured… this is who I am. this is where we are.

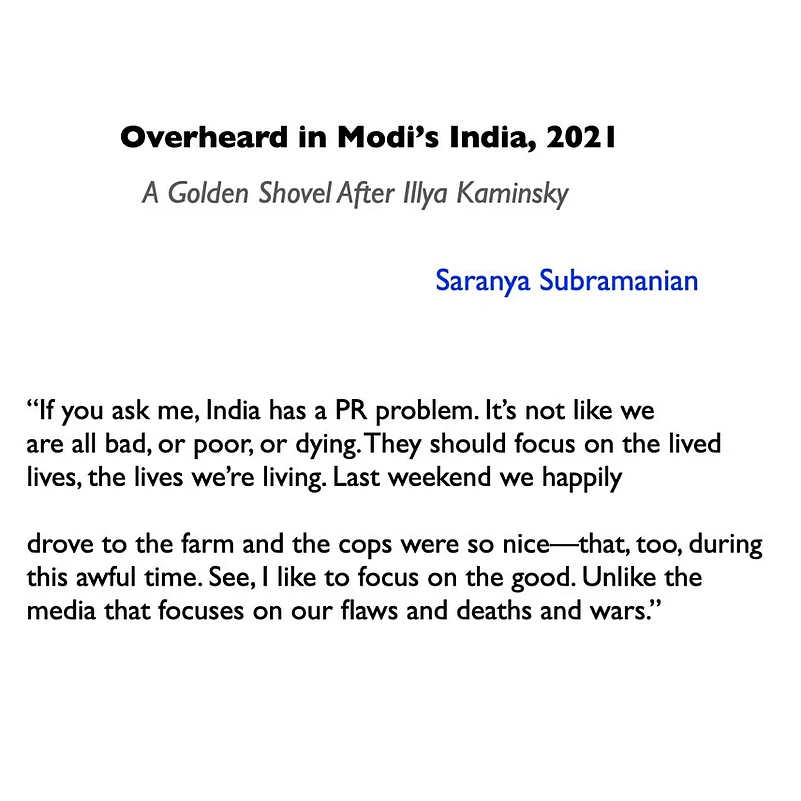

This is who we’ve become.” In one fell swoop, the poet renders her personal as political; the “I” as “We”; poetry as political testimony. In the way it is conceived – in its erratic chaos, it is – not a mirror – but a measure of public emotions; of world-making and world-breaking personal worries, and collective guilt. This is no mean feat, and what is even more impressive, is that it is wrought through an unselfconscious and uninhibited truth-telling, pulling the reader into the centrifuge of her concerns; that are universal in a way. The poem that first held me – shared by a friend in a poetry group – was Overheard in Modi’s India, 2021…

This is a fascinating poem for many reasons. The Golden Shovel is a form of poetry where the last word in each line of a poem forms a line or a stanza in a previous poem. So, for instance, this poem cites the prescient line “we lived happily during the wars” from an Ilya Kaminsky poem. The precision and sequential logic of this container for the poem is only enhanced by the fact, that it is used to render ordinary, everyday speech. Eavesdropping blooms in Saranya’s pen, as a methodology with which to apprehend the present. How many times have we heard such pronouncements, about Modi’s India? How many RWA retired uncles ask young people to “focus on the good”, as if ignoring the “bad” will make it go away? In the simple rendition of this oft-heard colloquialism, the poet pierces right into the decaying centre of the diseased body politic that is this country today. The apathy, and the indifference, comes home to the reader, in a quiet jolt.

There is an impertinence which trails the poet’s takes on political realities, and the dubious ways of power, and establishment. In a mischievous poem titled Prime Minister, at Night by Himself, the poet-persona humanises the divine spectre of the man behind the hologram. Describing mundane activities, sometimes with ominous repercussions, her portraiture derives a sensitive glee as it proceeds towards its final volta. He “stacks up his days/ like fresh Styrofoam plates/ one atop the other”… he twiddles his thumbs and distractedly “plays with matchsticks/burns drown hand-drawn maps/ prays to his forgotten father”. Just as an over-eager, politically charged reader might read the banality of evil into these pronouncements, the last line of the poem delivers the punchline: “who he really is/ leaks out/ wouldn’t you love him now”.

It occurs to me that only the wondrous precociousness of a young voice could ask that question, that too, in a debut work.

The Messiness of a First Collection

We live in a time where manicured lawns, blazing surfaces, and curated reels describe an aesthetics that is filled with the artifice of “perfection”. The pressure to be “always on”, in this world that flashes like a rolling ticker, means that most #unfiltered takes are designed with deadly precision. Thousands of rupees are spent on hired cameras for that perfect Instagram shot, even that ideal red-carpet look. Literature, and the arts, has not escaped this fate. We are caught in the vortex of carefully edited, and seamlessly put-together debut works. Books that are impeccable in their thematic array, with shiny edges, and sharp turns, tend to make bestseller lists. Subramanian’s collection doesn’t pretend to fall under the guillotine of “craftiness”. Oftentimes, the reader might discern the disparate themes, and the lack of clear connections between poems. Perhaps this might be seen as a weakness, but this is what endeared the book to me.

Consider these titles – “Travelling”, “Unpacking Academia”, and “Self-Portrait…”; “Outside the Prabhadevi Mandir” sits next to “After the Riots”; “Nights at the Delhi Border” plays a dissonant fifth to “Early Morning Alarms” or “Thatha Teaches Me Tamil”. My favourite, though, was “Instructions for Him for When He Reads These Poems”. The book does two things with a heaving sophistry: First, it channels the disorientation and chaos of an age of overwhelm, ridden with visual energy and a barrage of information that has rendered us numb. One of the defining characteristics of the present time, in the way young people – “content creators”, all – conceive it, is the impossibility of finding a coherent meta-narrative. Still, there are voices of opinion, and voices that “cancel” and “cut-off”, which pierce through the brouhaha.

These voices, while often being genuine, work mostly because of the self-confident finality of their pronouncements. Saranya’s book, on the other hand, calls a spade a spade, making no grand theory of critique or opinion. In its kaleidoscopic confusion, it unwittingly renders, with a startling felt clarity the state of the world we live in, and how we relate to it. There were several times, I felt the sentiment: “I have felt this too, you’re putting words in my mouth”. But there were times where I also felt: “Wow, aisa bhi ho sakta hain!” and when I re-read those lines, I realised the disarming honesty of the revelations. Instantly, they embedded themselves in my imagination, as felt experiences. This kind of “craft” is nothing less than the evidence of a connoisseurly hand at play.

Second, the eclectic nature of thematic concerns and formal experiments channels the persona of a contemporary “generalist” of sorts, whose practice, nevertheless, goes deep within multiple domains. Saranya’s interests are scholarly, but her interaction with these varied domains is intimate, and personal – from the confessional mode that lays bare the complexities of depression, to the concerns of an urban researcher, and one who is interested in multiple languages including classical Tamil poetry, Urdu verse, Kabir, and Monet. There is a line in her book where she acknowledges the seamless intersubjectivity of “languages” – from mathematics to poetry to melancholy. In fact, the twin-mystery of the essential trope that runs through the book – that of the Absent Presence, hits the reader both ways.

There is an arc that runs through the collection, and what works in the background, constantly, as we read these poems, is the notion of recognising the presence of a person, place, or phenomenon, by invoking its absence. This tropology is not an easy one to perform in poetry, and the delicate balance might spill over, at times, but in the last analysis, the book leaves you with several devastating images, catastrophic turns of phrase, and quietly resilient material memories. In this regard, the entire collection works as a metaphor – a metaphor for the movement from the self to the world in today’s fraught environment.

One of the conscious, and intentioned maneuvers of the book is the way in which it explores the idea of melancholy as a layered phenomenon, far more colourful, and textured, than joy, perhaps. One is aware of this idea, through the works of Van Gogh, who claimed that the night was infinitely more colourful, than the day. But in the range of experiences, sensations, and affects that Saranya taps into, across different registers of language, from the formal to the archaic, and the hackneyed, the reader is caught in the stiffening question mark that douses the human condition – the complex query of what it means to be a young, intelligent, feeling person in this broken world, who reads, interprets, and swims against the current. There were times, in this collection where I was rooting for the protagonist, but also times where I felt a comradeship of disdain, and rebellion, and this, for me, is the book’s greatest triumph.

Saranya Subramanian’s fiery debut collection of poetry, ‘Absent People, Absent Places’, published by Westland, can be purchased online on Amazon.