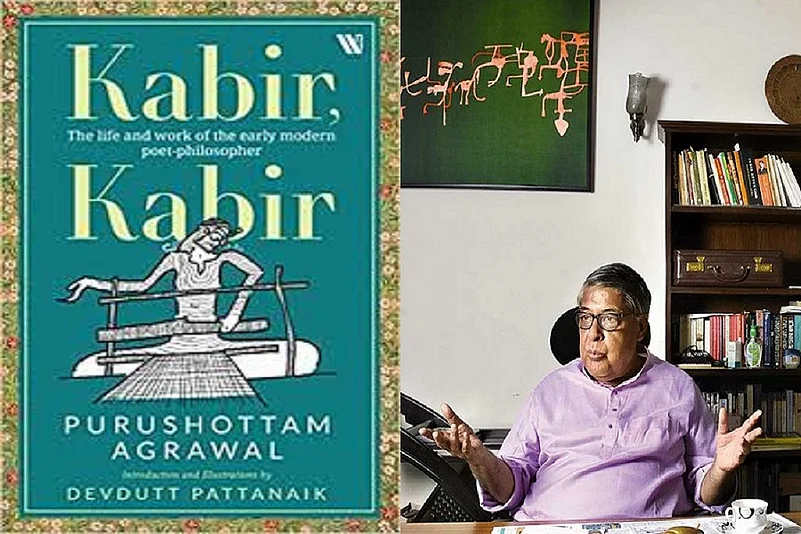

Kabir: The life And Work Of The Early Modern Poet

Purushottam Agarwal

Westland

Price: 399

Kabir is the only poet of the Bhakti period of Hindi literature, who continued to scoff at the rhetoric prevailing in society and among people throughout his life. He was an advocate of karma-oriented society and its glimpse is clearly visible in his works, by making a clear distinction from all other theological systems or traditions available at the time, writes Purushottam Agarwal in Kabir: The life and work of the early modern poet, published by Westland.

Agarwal has avoided a one-sided approach and given a balanced and equitable assessment of Kabir’s multifaceted personality and work. His present work must be considered a landmark in the literature on Kabir’s criticism.

Coming from the Nirgun Bhakti tradition, the words of this 15th century poet have the power to reach beyond time and speak to us today.

Was he a Hindu or Muslim, or was he beyond religion?

Did he try to cultivate a new faith, or did he eschew organised religion altogether?

Was his modernity an exception, or a reflection of the times he lived in?

What does Kabir’s life and poetry tell us about this nation’s past and present?

In this rare appraisal of Kabir’s writings and his life, Agarwal approaches the timeless poet-revolutionary with little preconceptions, presenting him the way the poet wanted to be seen, rather than what his followers and fans want to see in him. Enjoying the spectacle, Kabir wonders if anyone would bother to see through the “scene” and take the trouble to search beneath the surface. Would they be easily satisfied by the constructed perception?

The book is divided in six comprehensive chapters across unusual themes: ‘Approaching Kabir’, ‘There Lived A Weaver in Kashi’, ‘East and West in Kabir’s Time’, ‘Life is Transitory and Kabir Composes Poetry’, ‘Bhakti: Morality and Moksha in Everyday Life’ and ‘Erotic to Divine’. In subsequent chapters, as he compares the writings and interpretations of Kabir’s teaching across different sub-sects, he also points out the flat binary interpretation of European scholars.

The core idea is individuality, moral choice. Agarwal gives a different outlook or perception about pre-British India in this book. His argument is that pre-British India was not a static society, making it a book on the history of ideas and evolution of morality as well.

Agarwal has also delved into details of Kabir’s knowing or unknowing statements on internalisation. He affirms that the reason one finds a lot of Nath Panthi elements in Kabir is because his forefathers were recent converts from Nath Pantha Yogis to Islam. If you find so much Hinduism in Kabir, it’s because he had Hindu ‘blood’, though not Brahmin roots. If you find so much of Islam in his poetry, it’s because he was a Sufi. A refreshing insight into pre-colonial Indian society and thought, making the book a great act of storytelling.

The author also tries to establish a narrative on how Kabir was represented in his times, and how he reflected them. In the same way, Surdas from Gwalior has composed Mahabharata in Hindi. Ramcharitmanas by no stretch of imagination is a translation of Valmiki Ramayan. It is this vernacular intellectual ferment that led to the creation of a public sphere of Bhakti, he contends. Agrawal doesn’t restrict his views on Kabir just to his spirituality. He travels further on, narrating the socio-political scenarios of 15th century India. Even then, he keeps it factual, rather than provoking any such conflicts.

According to Nath Pantha Yogis, Gorakh is the liberator. According to Hindus, Ram is the liberator, while Islam is based on monotheistic theory of God. But Kabir says, “My God dwells in the entire universe, in the existence of a whole”. He makes a distinction from all existing theological systems or traditions. But he never says he wasn’t born a Muslim. He is clear, and so are his contemporaries. Kabir rejected the hypocrisy and misguided rituals evident in various religious practices of his day, including those in Islam and Hinduism.

As he unravels the mysterious life of this 15th century Bhakti poet and philosopher, the author analyses with precision his works, diving into the metaphorical meaning of Sakhis written by him. The poetic conflict between Tulsidas and Kabir is also discussed. They had different perspectives on achieving moksha, and conceived the almighty in different ways.

Agarwal writes ‘Anantdas tells us that, “Kabir tried to keep away from his fame, like a demure, young woman hides her baby bump.” But people thronged around him day in and day out. He was left with hardly any moment to himself, hardly any of the privacy and solitude he craved to be able to reflect and to be in “dialogue with his Ram”.’

As the Right tries to claim Kabir for itself, while other conservatives disown him, and yet others portray him as a secular idol beyond religion, the poet has never been so misunderstood.

Agarwal further writes: ‘Kabir’s is the universal dilemma of creative and reflective souls. He spoke and sang about the bliss and agony of finding a way to connect with and touch people, and the ambivalence he felt about the resulting fame, of the mania of those who desired a connection not just with his words but with him.’

Kabir is known for being critical of organised religion. He questioned meaningless and unethical practices of all religions, primarily those of Hinduism and Islam. Kabir suggested that ‘truth’ is with the person who is on the path of righteousness, considers everything, living and non-living, as divine, and who is passively detached from the affairs of the world.

The book focuses on Kabir’s evolution from a disciple to master, from Shakta to Vaishnava, and how with time, his teachings were modified into other sects, including Sikhism.

Reviewed by Ashutosh Kumar Thakur, a Bangalore-based management consultant, literary critic and co-director of Kalinga Literary Festival. He can be reached out at ashutoshbthakur@gmail.com