On January 15, day one of the Jaipur Literature Festival, the sun shone bright. The air in Jaipur, compared to Delhi’s doomed smog, felt more breathable. Crowds pooled around the gates of the festival venue. You could hear people debating which sessions to go to, which authors to get signed copies from, who was approachable, who would play the diva. The 19th edition of JLF, the festival that has placed India firmly on the global art and culture map, was off to a lively start. Many at JLF had plans to head to other lit fests afterwards—Kolkata, Chennai, Kerala and Hyderabad beckoned. January is ‘lit fest season’, but the season is by no means short-lived. The months that follow too will be hosting fests across a multitude of locations.

This year lit fests take on a special resonance. Why? Because the year of our lord 2026 has been declared the ‘year of analog’, a widely predicted cultural trend that sees us tiring of digital overstimulation and returning to tactile real-life experiences—savouring the pleasure of reading physical books; meeting each other face-to-face; less doomscrolling, less texting, more nature walks and strolls on the beach, feeling the sun on our skin and the wind in our hair instead of staring at a screen with distracted eyes.

As we slow down and our attention spans deepen, our relationship with lit fests may evolve. It would be interesting to see how fests respond. Some things will surely change, but some are bound to stay the same. For instance, the reasons that compel writers to head to fests in the north, south, northeast, west and east. Why trudge to beaches and desert towns? Why travel to the dusty plains? To engage with readers—who may be adoring fans or strangers who ‘discover’ you by accident at a session. There’s always the hope that at least a few will then be tempted to buy your books. Fests also give writers a break from solitary slogging and to have “long-deferred conversations in the shadowy recesses of authors’ lounges and dining rooms’’ as poet and writer Arundhathi Subramaniam puts it. British writer Geoff Dyer, a diehard lit fest enthusiast, enjoys meeting other writers at fests in faraway places. He’s built some lasting friendships this way.

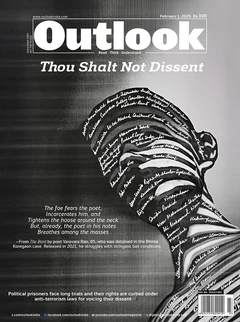

To readers, lit fests offer a rare opportunity to hear writers speak in person. Titash Choudhury from Kolkata is delighted about getting signed copies from many of her favourites, including Abdulrazak Gurnah, Amitav Ghosh and William Dalrymple, at the fests they attended in her city. Devnath, a Kozhikode resident, treasures his memories of hearing K.R. Meera speak at the Kerala Literature Festival. He’d read all her novels and it felt like a dream to interact with her. Shalmoli Halder, a senior strategy consultant who reads widely and follows the work of Indian-English writers closely, once heard British playwright Tom Stoppard speaking at a fest. This inspired her to read all his plays. She is grateful to the festival organisers for bringing Stoppard to Indian shores. Roma—a Hyderabad resident who works at an IT company—likes to tune into the conversations at lit fests, which she says cover “everything”—from history, geopolitics, gender, the climate crisis and AI to fiction and poetry. It helps her see the world with fresh eyes.

“There’s food, friends, music and colour at literary festivals. But as long as books are getting attention, it’s a good thing for authors and readers.”

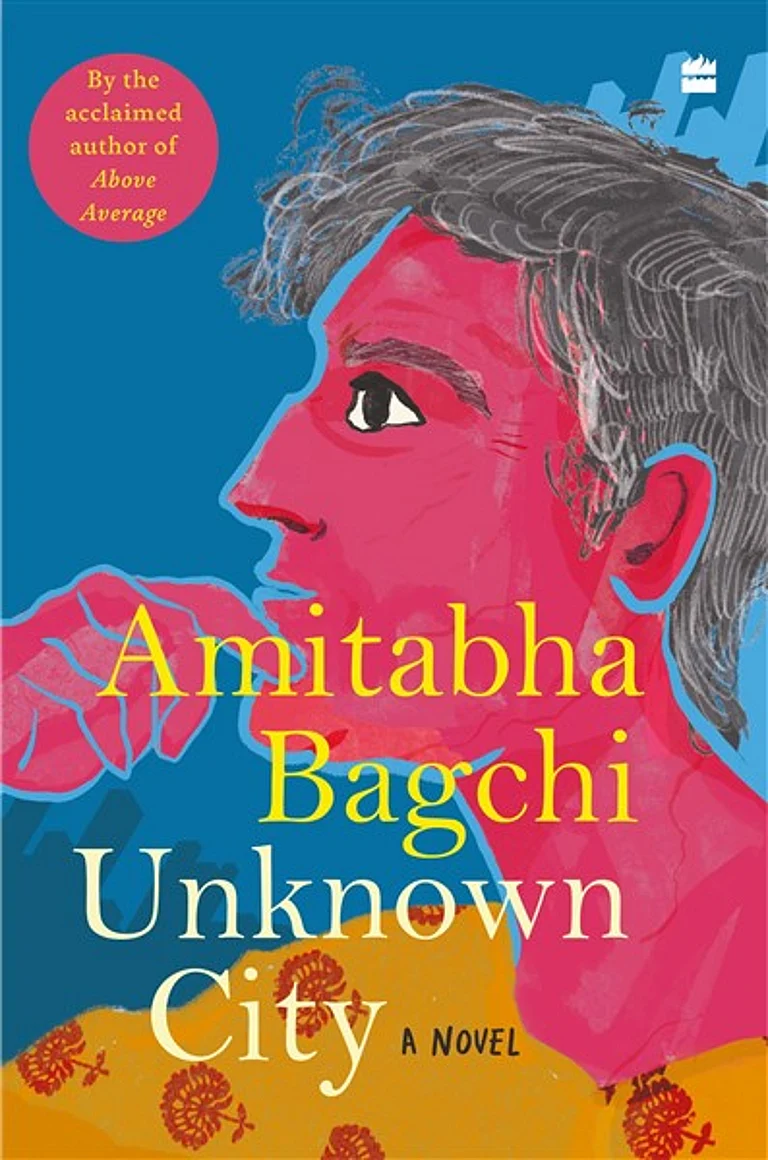

On publishers’ calendars, literary festivals are a major highlight. “Lit fests are a perfect marketing vehicle,” says Ananth Padmanabhan, CEO, HarperCollins India. “A great platform to showcase our authors and introduce new writers.” He is excited about the fact that at most lit fests in India today, about 60 per cent of the audience is made up of people under 25. Since lit fests are one of the “dedicated avenues” for promoting books and making author-reader interactions fun, they are a core area of focus says Pallavi Narayan, GM-Corporate Communications, Penguin Random House India. Festival appearances can boost sales and generate a sizeable amount of interest in an author’s books. To new authors, festivals offer a stage to address a large audience, which isn’t easy to come by. Dibyajyoti Sarma, founder of Guwahati-based independent publishing house Red River, wishes lit fest organisers would pay more attention to small press writers. He says that since big publishers have an advantage structurally, their marketing reach makes them far more visible to organisers.

Literary agent Hemali Sodhi, founder of A Suitable Agency, points out that many key festivals also provide networking opportunities for publishing professionals to get together. “This paves the way for closer collaborations—the Jaipur Bookmark being a prime example.”

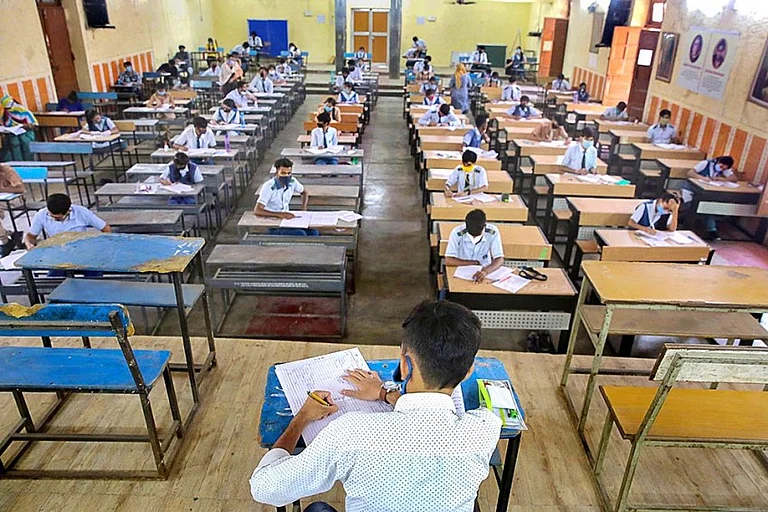

Argha Banerjee, Associate Professor & Head of the Department of English, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata, wouldn’t miss lit fests if they were to fade away. Authors and readers can interact at book fairs, can’t they, he asks. His concern is whether the lit fests in India are addressing the urgent need to develop the reading habit at the junior/middle school level. “This is crucial for the future,” he says, suggesting that starting small lit fests for children, making participation mandatory across schools, would nurture readers. Rural areas also need more such initiatives.

Ashok Kumar Bal, CEO and Patron of the Kalinga Literary Festival which celebrates linguistic diversity, says that the fest holds book review competitions and inter-school debates for students in Odisha. The Kolkata Literary Meet has programmes for young readers. Students from local schools and colleges are encouraged to attend the Jaipur Literature Festival every year.

Lit fests are not isolated entities. Poet and cultural critic Ranjit Hoskote notes that “they are part of a large and complex tapestry. Many contributors are involved, all of them interconnected. We must take book fairs, bookstores and libraries into account when we talk of nurturing the culture of reading and writing.”

***

Zac O’Yeah, the Swedish writer who has made Bangalore his home, remembers a time when lit fests were new entrants on the Indian scene. He feels the excitement has dulled now with festivals sprouting in every corner. When he did the round of fests with his most recent book Digesting India (2023), he found the celebrity quotient and the selfie-takers and reel-makers distracting. “It’s a bit of a tamasha,” he sighs. “How much intellectual discussion are authors engaging in?”

Malavika Banerjee, Director of the Kolkata Literary Meet, says that her job is to stay true to the original mandate of a literary festival: ensure that books and ideas which spark intellectual inquiry remain front and centre. “The surround sound of celebrityhood exists,” she acknowledges. “The challenge is to find a balance and stick to the original mandate…I see myself as a curator rather than a caterer.”

At big fests, attending multiple sessions and flitting from one session to the next can be overwhelming for both writers and audiences, says K. Srilata, Chennai-based poet, translator and academic. She finds the smaller, feeder events organised by festivals like The Hindu Lit for Life as a run-up to the main event an effective model. “The Sahitya Akademi festivals that invite writers who write in non-mainstream languages so that the focus is not too Anglophone—that helps too,” she says.

Some may find lit fests in India to be too much and too many, but don’t we have too much of everything here, asks Arunava Sinha, translator and Professor of Creative Writing at Ashoka University. Choudhury feels the more festivals the merrier because it means that if you miss an author at one festival, you can listen to them at another. “Spares you the agony of FOMO (fear of missing out),” she says.

Hoskote notes that every festival has “its own ethos and scale like the ones held at Goa or Ooty or Mysuru…And each festival has its committed local audience that is nourished by bookstores.” Subramaniam is thrilled to have met interesting people in places as diverse as Kasauli, Bhubaneswar, Shillong, Bhopal, Nagpur and Chengannur thanks to lit fests. “But what I feel the need for today—as listener and participant—is the solo event which holds space for the voice of a single writer and allows for deeper conversation and deeper reflection,” she says.

Many festivals are garnering big crowds. JLF caps physical attendance at around 350,000 for the main festival and has about 30 million unique viewers online says Sanjoy Roy, Managing Director of Teamwork Arts which produces JLF. The Kolkata Literary Meet’s last edition had over 75,000 on-ground attendees and a large audience for its digital livestreams. The Kerala Literature Festival attracts a pan-India audience as well as international attendees. The Kalinga Literary Festival has also been hosting packed sessions. So, do big numbers guarantee a bright future for books and authors? Not necessarily.

One oft-repeated gripe about lit fests is that many attendees sashay in, all dressed up and ready to be clicked, with no plans to read. “They come to be seen. Or for the music or the food stalls,” says Vibhash Jain, who shares a bittersweet bond with lit fests. The IIT Delhi student who used to write poetry in his school days, (before the world crushed the poet in him), goes to fests to soak in all the talk about books and literature. He listens and learns; always the observer, never the insider. “The music and food at fests are optional,” quips S. Ganesh, a Delhi lawyer who feels our lives would be impoverished without lit fests. “Skip the music and the food if that’s not your thing,” he says. “Listen to authors talk. Go read a book.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Vineetha Mokkil is senior associate editor, Outlook. She is the author of the book A Happy Place and Other Stories