Summary of this article

Presented by the Ishara Art Foundation and Aazhi Archives in Mattanchery, Kochi, the exhibition moves between categories, unsettling fixed binaries.

The exhibition explores amphibious modes of existence that transcend borders. Borders of land and water, vulnerability and adaptability and past and future.

The exhibition of 12 artists and collectives, whose works engage with questions of precarity, ecology and survival, ends on March 31.

The crises of the Anthropocene are no longer distant or abstract. They are part of everyday life, as evidenced by a warming climate, fractured politics, displacement, alienation, and the growing dominance of capital. Even as these realities are widely acknowledged, human actions continue to intensify them. Living with such uncertainty and instability has shaped how artists respond to the present. Amphibian Aesthetics takes shape within this fragile moment. Presented by the Ishara Art Foundation and Aazhi Archives in Mattanchery, Kochi, the exhibition moves between categories, unsettling fixed binaries and quietly questioning the hierarchies that organise the contemporary world. Set within the Kashi Hallegua House, a 200-year-old building in Mattancherry, the exhibition draws on the layered histories of the space to present artistic responses to the derangements of our time.

The exhibition draws inspiration from the term ‘amphibian’, which refers to animals that spend part of their lives in water and part on land. The exhibition explores amphibious modes of existence that transcend borders. Borders of land and water, vulnerability and adaptability and past and future. The exhibition brings together 12 artists and collectives from South Asia, the Middle East and Europe. Their works respond to or play with emerging precarities of the world.

“Amphibian Aesthetics emerges from a long arc of work that has unfolded in Kochi over the past 12-15 years, continuing the conversations that have been carried through projects such as the Mattancherry Project (2016) and Sea a Boiling Vessel (Kashi Hallegua, 2022) through the formulation of our organisation Aazhi Archives”, says artistic director Riyas Komu. “At its heart, the amphibian becomes a metaphor for adaptability and shared vulnerability—a figure capable of moving between land and water, past and future, material and immaterial conditions. This amphibious sensibility resonates with the broader conditions of precarity in which contemporary art now operates: ecological collapse, forced displacement, extinction, and hyper-capitalist acceleration. Amphibian Aesthetics proposes a hydro-social, multispecies framework for imagining coexistence. It foregrounds water’s agency, the porousness of boundaries, and the need for collaborative survival beyond the human. Through this lens, the amphibian becomes not only a metaphor but an invitation: to inhabit uncertainty, to reconfigure relations, and to craft new imaginaries for a future shaped by contradiction, crisis, and interdependence.” Komu added.

One of the artists featured in the exhibition is Michelangelo Pistoletto, an Italian artist. His ‘Division and Multiplication of the Mirror, starts with the observation that a mirror can reflect anything except itself. However, by dividing a framed mirror into two parts and gradually moving the two halves along the dividing line, it can be observed that the number of images in the mirror increases as the angle between the two parts narrows. The principle of division manifests itself as the universal foundation of all organic development and, at the social level, as sharing, an alternative logic to that of accumulation and exclusion. His work ‘Free Space’ is a large steel cage with no entrances, with word 'FREE SPACE' pasted above. Free Space was first created in 1999 as a a collaboration between Pistoletto and a group of inmates at the San Vittore prison in Milan, who executed and installed the work in the courtyard of the prison where they were incarcerated. “It was made inside the jail that is already a cage, where everyone feels deprived of their liberty. We assume that there is freedom outside the jail. I created for them a free space within the jail—a mental space, a behavioural space, a virtual space that embodies the concept of freedom of thought, the truest form of freedom. Even in situations where you are inside a cage—like those of a concentration camp—the only thing that you have is the freedom of your thoughts, which nobody can take away from you. That is true inner freedom.” Michelangelo Pistoletto had said about his work.

“Michelangelo Pisteletto has predominantly worked with mirrors to create art. He uses broken and splintered mirrors for the spectators to gaze, see oneself and the world behind and beside them,” says curatorial advisor, C S Venkiteswaran. “So, in that sense, looking at them is a self-splitting experience. Against these broken mirrors is a huge iron cage, closed from all sides, named ‘Free Space’. While the cage forbids you to enter its free interior, the mirrors cage your reflection. They duplicate you, capture you as an image and prompt you to look at yourself, suddenly evoking the amphibious nature of this dual existence of ours, where we try to be like our image. The metaphor of mirrors also has additional resonance in the Kerala context, where the great philosopher-reformer Narayana Guru placed a mirror as an icon in temples”, he adds.

The theme of the cage recurs in Pistoletto's artistic pursuits, including in the multidisciplinary art group Lo Zoo, which Pistoletto founded in the 1960s.

T Ratheesh’s The Indian Garden, with unknown flowers , engages with the country's social realities, such as the Brahmanical patriarchy’s emergence as a political force through religious communalism. His works reflect the contemporary political realities and the anxieties they produce. The crisis, like the Kerala Flood of 2018, and COVID-19, Ratheesh finds tragedy and revelation: the collapse of infrastructure and governance, and the resurgence of resilience and care.

“Ratish’s work is a meditation upon the subtle and subterranean ways in which caste works in Kerala society. These vertical panoramas with three layers of image-sets speak about the state of the subaltern,” says Venkiteswaran.

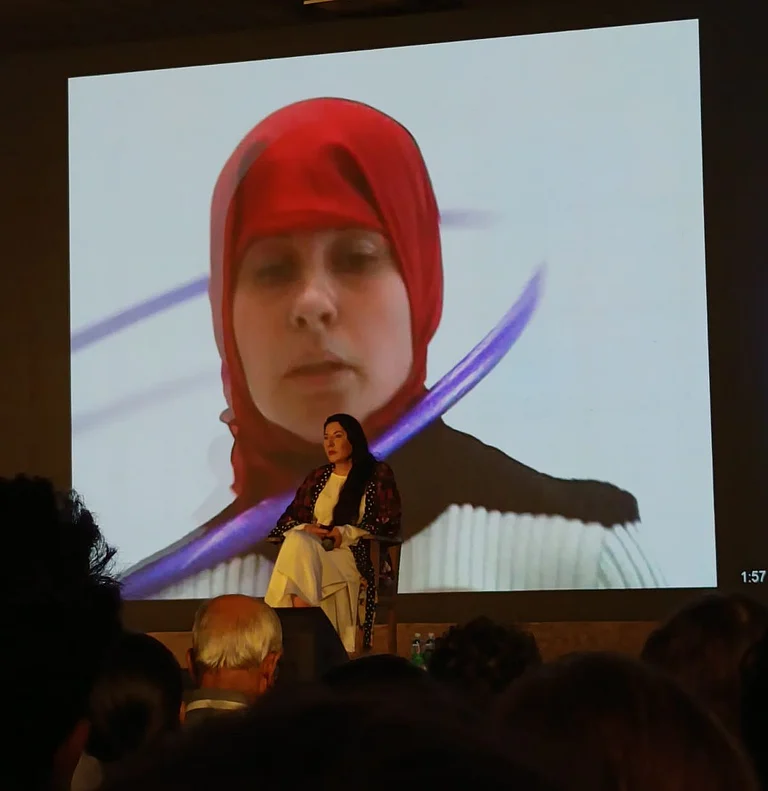

Palestinian artist Dima Srouji’s ‘Foundations’ uses sound and space and traces what remains and what has been erased from the ground in Palestine across time and place. In 1930, British archaeologists exhumed a tomb from ancient Gaza. The installation begins from there, and the tomb’s outline becomes a vessel for reimagining the displaced soil as a returned monument for gathering and as a ground that refuses disappearance. The sound layers reversed recordings from the unfolding genocide, moving past October 7th 2023, to expose the colonial continuum across generations. It ends with an interview with the artist’s grandfather, played backwards, as he recalls life in Palestine during and before the Nakba. Srouji collaborates closely with archaeologists, anthropologists, sound designers, glassblowers, and stonemasons. She has exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Biennale, Sharjah Architecture Triennial, the V&A, and the Palestinian Museum.

The World of Amfy B.N. Jose X Frogman, delivered as 20-plus digital works, Appupen, invites viewers to question the ease with which villains are made and myths maintained. Through dark humour and satirical storytelling, the series probes identity politics, surveillance, ecological anxiety and propaganda. The exhibition of 12 artists and collectives, whose works engage with questions of precarity, ecology, and survival, ends on March 31.