Summary of this article

The Kochi–Muziris Biennale 2025–26, curated by Nikhil Chopra as For the Time Being, is deeply entangled with questions of labour, politics, censorship, and institutional responsibility, while still drawing massive public engagement and reaffirming art’s power to unsettle, resist, and provoke dialogue.

Fort Kochi itself becomes part of the Biennale, where everyday life, urban textures, local labour, and informal aesthetics merge seamlessly with curated artworks, blurring boundaries between “art” and “life” and turning the city into a living, sensorial ecosystem.

The curation foregrounds global and local struggles—caste, borders, migration, ecology, and war—through material-driven, site-responsive works that invite slow, embodied attention and reflection on interconnected human and more-than-human worlds.

It is impossible to think of the Kochi Biennale simply as an aesthetic phenomenon – an artistic “event”. Considering the turbulence that has dogged its previous editions, one cannot speak of the Biennale with innocence, or in isolation. Questions of labour rights, financial mismanagement, fair pay, and other institutional issues have marred the organisaiton, and in the run-up, commentators wondered whether the curators would successfully carve out a meaningful future for the festival, from the hollow of the pandemic, and its still-present impact on the world. Going by audience response alone, however, thus far, it has been a grand success, with an estimated footfall of 1.6 Lakhs in the first twenty days alone!

Helmed by Nikhil Chopra, and HH Art Spaces, the curation entitled “For the Time Being” also came under the scanner for the way it has negotiated its responsibility towards a politics of expression. Artist Tom Vazhakutty was forced to withdraw one of his works, after Catholic fundamentalist groups protested over an interpretation of the canonical Last Supper. This kind of backlash is not surprising, in a deliberately polarised and fraught political environment. But what is impressive is the organisers’ response – In a letter to the local police, erstwhile President Bose Krishnamachari reiterates, “The Kochi Biennale Foundation does not believe that the artwork in question warrants removal.” This was before he stepped down from his post, citing “pressing family concerns”, and the intent to “go back to artistic practice”. Nevertheless, this act of faith – standing by their artist – marks a significant step towards sensitivity for communities, and cultural practitioners, foregrounding the revolutionary power of art to unsettle regressive notions that gain traction in the frenzy of decontextualised “offense”, and heightened public emotions.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale as a Public Phenomenon: Art-City Kochi

The ellipsis in the title of this article is deliberate, mirroring the air of reflection and slowness that stays with the viewer navigating the side-streets of Fort Kochi, finding art in unexpected places, in the shadow of the larger event. The Biennale, after all, is an iconic “exhibition” – a kind of showcase. The inhabitants are inevitably a part of the notional “ensemble”, and their welcome extends to an emotional, but also, entrepreneurial and creative zeal. Many of the artworks are made in collaboration with the skilled workers, artisans, and artists of Fort Kochi, indelibly marking the event with the political and cultural currents of a place that is nowadays termed “touristy”, in a curious mix of modernity, tradition, and aesthetics. Walk into the sidestreets, and you will encounter a galaxy of small worlds of industry, manufacturing, and trade, with local food stalls, churches, masjids, and so on. People, caught in everyday activities of fishing, and transporting wares, are often oblivious to the Biennale. When visitors to the big event stray into that other world, the people, used to speaking with annoying tourists – who don’t know Malayalam, and who are prone to romanticisation of the “locals” – continue to be warm, and helpful. Often they are unable to hide their amusement at this gaze that Biennale visitors tend to have, even the visitors from other parts of Kerala such as Trivandrum, or Calicut.

Art is literally everywhere; in the carefully swept-up yellow copper-pod petals by the jail house venue (where posters, maps, and archival material from the Ebrahim Alkazi Archive were displayed), in the creatures and urban forests muralled into bare walls and building facades (some of these double up as unobtrusive “promotion” for the Biennale), in a vision of pigeons calmly looking down at the gaggle of visitors entering a historic church, in the graffiti and sign-boards which have nothing to do with the Biennale (but often allude to it), and the many posters that collage into palimpsests of torn and re-juxtaposed imagery on the walls, like smiling faces.

In short, the event has become so entrenched in the (extra)ordinary of Fort Kochi, that it is difficult to separate “Biennale Art” from “urban aesthetics”. Visitors experience a deepened attunement of the senses; a slowing down, and hollowing out, of the present moment – letting the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures wash over them.

And so it is, that, more than once, you are not sure if a tableu’ is part of the Biennale or not! “Here, everything is art”, one of the visitors exclaimed, unsure if the graffiti on the wall before them was a part of “official curation”. This thrill of synaesthetic discovery enhances the curator’s vision of the event as a “performance”, always moving, and finding stillness, even in movement. Event promotions, cinema posters and political signage plaster every wall of the city, conversing with both the “hand-made” and the digital, “graffiti” and “mural”, recasting the question of everyday aesthetics, and what happens to a work when it is “curated” in a white-cube space. One of the works that is a part of the Student Biennale curation – that looks exactly like the walls on the street outside, but noticeably different, because of the absence of the “digital” – crystallises this question.

“The Visual Voices of Kerala’s Politics” (2024), a photo and design research project by Neetha Joseph Kalappurakkal, documents “the rapidly fading practice of hand-painted political graffiti across eight urban centres of Kerala”. The replication and hyperreal curation of these images slapped onto the wall convey the complex social role of these visual cultures in a single frame, along with the complexities brought on by digital aesthetics – the medium is the message, after all. In many ways, the Student Biennale curations, along with the other works, deepen the notion of how the visual sociality of a place collides with the “displayed” art.

The encounter with this edition of the Kochi Biennalle, thus, is not simply an encounter with the artworks – it is an encounter with Kerala, the island of Fort Kochi, extending into Ernakulam; it is an encounter with the sea and its stories, and the labourers, makers, and doers, the inhabitants, who make the space what it is. You will rarely see people angry with visitors taking pictures of themselves in front of homes, graffiti’d walls, and shop windows. If anything, it is the visitors who are to blame – those who are unable to shut down the impoliteness of their strange gazes, and the solipsistic urge to photograph themselves in every space.

It is this sensibility of place that this year’s edition has tapped into. There is a reflective air to the curations, and a sensitivity that is embodied in Chopra’s invocation of “friendship economies” and extension of the lived space of the Biennale – shops/side-streets/and go-downs included – as a performance. Chopra speaks of the “living eco-system” that allows the art to come alive in myriad ways, and the title reflects this interaction between movement and stillness. To borrow a concept proposed by the new materialist philosopher Jane Bennett, the Biennale, this time, embodied a “political ecology of things”.

The Curation : A “Political Ecology of Things”

The visitor to the Biennale quickly shifts their gaze from the subjective space of judgement (“What did you think of the Biennale, and the curation?”), to the more introspective impulse of forming an intuitive horizontal relationship with the shapes, forms, and colours of the works; even the conceptual and political ripples of individual curations, especially the ways in which the works are embedded within the backgrounds and contexts of the different venues – warehouses, halls, and abandoned buildings.

This deepening of “sense” into “sensitivity” is evident in the profound engagement with more-than-human entanglements, and the rhizomatic glocal ecologies. Many works move the average viewer of art to think about transnational and migratory economies that explore different cultures through their artifacts. In a fascinating array of artworks, both Indian and International artists interact with local environments; materials such as fishing nets and hooks become conduits of historical trade routes, and cultural exchange.

The Congolese artist Sandra Mujinga’s Remember Me stages an encounter between two other-worldly creatures made of local material, draped in fishnet – as tribute and referent to the local fishing communities and their inherited living knowledge. In the same abandoned warehouse, in a corner, the Grecian artist, Athina Koumparalli’s Deep Time (2025) unfolds in broken translucent interfaces of computer screens and devices “hung” on bamboo scaffolding tied together by jute. It is likely that you will be surprised by a shock of pigeons roosting and responding to some of the sounds in the installations, and the spaces will transform, momentarily, into imaginariums with creaturely energies across centuries interacting in the “deep time” of the present.

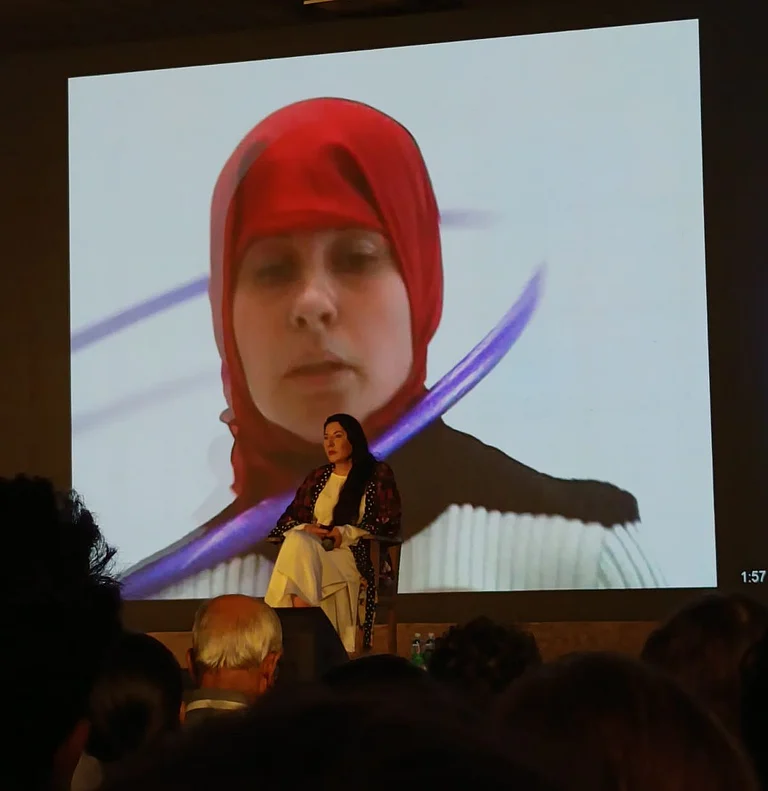

It is significant that this edition of the Biennale foregrounded the ruptures and disruptions in nation-state, borders, caste, and community, with renewed fervour. Drima Srouji’s work in different venues embodied, with astounding sharpness, the atrocities enacted by the Israeli state on the Palestinian people. Air of Firozabad/Air of Palestine (2025) was created in collaboration with Italian artist, Piero Tomassoni. The work is made up of hundreds of transparent glass baubles suspended from the ceiling reframing Duchamp’s collected 50 cc of Paris Air (1919) using the poignant metaphor of life-force, and its scarcity in the devastating aftermath of the oppressor’s settler-colonialist attack. These baubles transpose different cultural spaces of production and conflict to the coalescing shadow and light of an eerily quiet interior – a small room with a roof, and aesthetic jaalis – transforming it into a symbolic gesture that brings home the absurdity of this war that has been normalised into our everyday; through a metaphor that inhibits the material force of air, that is superfluous, but life-changing.

Srouji’s other work at the Hallegua House, part of the curation by Ishara Art Foundation with the artistic direction of Riyas Komu, entitled Foundations (2025) uses blocks of brick and plaster replicating the plan of an exhumed tomb from Ancient Gaza, excavated in the 1930s by British archaeologists. It is a telling index of “what remains and what has been erased from the ground in Palestine”. It lives besides two dark rooms full of wooden furniture, glass panes, and table tops that conjure up a sonic staccato chorus of Faiz’s iconic Hum Dekhenge. This is an installation by Shilpa Gupta – a work that grows slowly in the viewer’s senses. Her other work, at Ginger House Museum Hotel, called Sound on my Skin, is a 35-minute text-based motion flapboard. This contraption replaces the details of departures and arrivals in airports with foreboding text that gradually winds up into horrific collisions of “walls”, “lies”, “self”, “borders”, and various political articulations that constrain and convulse modern life. The synesthetic juxtapositions she stages locate the body in ever-expanding spirals of alternating fear, rage, and constriction, bringing home the everyday instances of political violence that give currency to the idea of a “doomscroll”.

Prabhakar Kamble’s installation work Vichitra Natak uses materials of the “afterlives” of craft, labour, and skill, to place the social inequalities of caste architecturally against orthodox notions of aesthetic purity that otherwise justify Brahminical supremacy, and even “art-school” notions of abstraction. Inspired by author and philosopher Gautamiputra Kamble’s words, the installations (including chandeliers, rotating instruments, and animal sculptures) works with sounds, visuals, and forms usually reappropriated as “folk” aesthetic, to stage a system that supports caste, rather than foregrounding the actual violence that is routinely used to shock audiences.

Kamble’s works conversed with curations by the Secular Art Collective in the Student’s Biennale, that told stories of labour’s intersection with caste, explored through personal stories of historical oppression. This was seen in works like Ginning Justice that included Sachin Banne’s material exploration of the journey of Manjarpat (Manchester cloth) from its imperial roots, to colonial exploitation of the workers who toiled to produce it.

Perhaps all these political debates converge at the breath-taking installation by Ibrahim Mahama. The work, titled, Parliament of Ghosts, consists of a large room whose walls are carpeted by sack-cloth stitched together by women homemakers from Kochi, and a crowd of “rickety chairs” stabilised by Kochi’s carpenters – placed in a mise-en-scene that emulates large public discursive spaces. The emptiness of the space echoes with questions of the colonial legacy of exploitation of the labour of native inhabitants.

It is impossible to list the body indivisible and politic that animates the spectre of Chopra’s vision of extended performance. Many of the works that perform the collision between the lived ecology of earth, sea, and sky with the human animal, propel an instinctive aggregation of awareness in the mind of the visitor to the Biennale – a heightened, almost meditative attention to the smallest objects, but also the impossible interconnectedness that thrust these “things”, peoples, and spaces into the cosmic terrain of the Anthropocene. It would be hyperbole to claim that the art propels this awareness. But one can safely say that the intricate ecosystem unfurled by the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2025-2026 creates the conditions of possibility for such a material and philosophical dialogue to take place.