Summary of this article

Abramović is a high priestess for anyone in the art world.

Art has always existed in close proximity to political and socioeconomic power.

Showing up for art is showing up for human connection.

There were no nude couples to squeeze past at legendary performance artist Marina Abramović’s lecture on Willingdon Island last week (trademark Abramović). Instead, one made one’s way past a steady parade of patrons and socialites who were sashaying over from the nearby art venue showcasing one of the artist’s pieces, or, perhaps unwilling to schlep a few hundred metres in couture, being driven directly to the entrance of the Samudrika Convention Centre, where attendants seated them. One of the key art events of the year, the evening featured many visitors from Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Goa, as well as international tourists who were already in town and local students. Many of the latter had already earnestly inducted themselves into the micro-universe of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB), now in its sixth edition.

Abramović is a sort of guru, a high priestess for anyone in the art world; an icon, with rockstar status. Tickets had sold out almost immediately, while there were reports of some being auctioned off, possibly for more than the original Rs 1,000, to the queues outside the venue. We were posting images of her—prophet-like, in her customary flowing garments, white this time—on social media even as the event ended, warnings about being distracted by technology notwithstanding. No matter: this audience was indisputably present. And, performing for each other. In our current moment, when millions of performances are broadcast around the world and going viral, this is par for the course. What was noteworthy was the excitement and engagement of a jaded public.

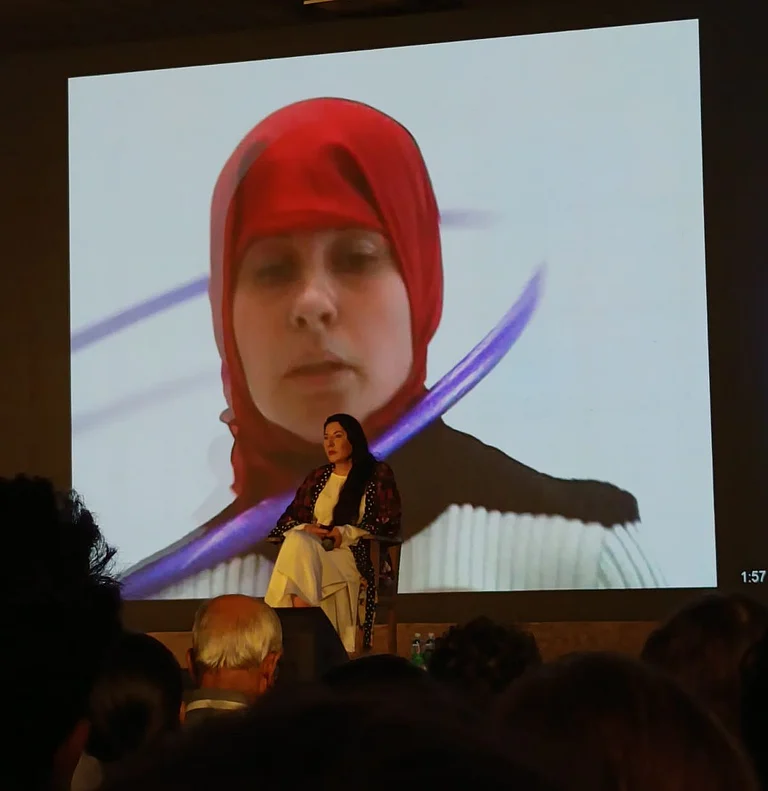

A couple of hundred VIPs and press people sat in the first dozen rows; others were cordoned off, watching the lecture mostly on an adjacent screen, the stage being too far away to properly view the star of the evening. What a thousand of us were watching, as much as the presentation, was that inscrutable face. This artist signifies much just by her radically intense presence. As curator Klaus Biesenbach has noted, she created a ‘rent in the fabric of the universe’, a ‘charismatic space’ simply by sitting in a room at ‘The Artist is Present’ (2010), her three-month NYC performance, wherein she gazed into the eyes of strangers, many of them subsequently reduced to tears. This is the Abramović effect, and she has acquired a talismanic, hypnotic quality.

Those who have heard of the artist’s extreme acts—subjecting herself to violence by allowing the audience to do anything they wish to her by placing items, including guns and knives before them, most famously, and passing out in a burning five-pointed star—may have expected more of an ‘intervention’ (the artist’s term for certain kinds of performances). But while the seven-minute moment of collective silence Abramović led at the Glastonbury Festival in 2024 was mirrored by our collective intake of twelve deep breaths in Kochi, following stern instructions (‘I ask you first, not to cross your legs… [forget] your watch, telephone off, no technology’), the lecture was basically a primer in the artist’s medium of choice. Which led to disappointment in some quarters—while acolytes were seen beaming at the opportunity just to breathe the air in the same room, air-conditioners be damned (Abramović welcomed the reduction in noise when one was switched off by the stage). Unlike some of her peers, who are often past their prime, she is active, alive and pressingly contemporary. And, at an uncannily youthful 79, she exudes an intimidating calm, unflinching despite the brutal images she guides us past (live fireworks against a man’s leg, an eyeball being sliced open).

“She inserted herself in every aspect of the lecture,” the Kochi Biennale Foundation (KBF) team responded when asked about the choice of format. Indeed, for the uninitiated, the two-hour presentation is a useful personalised tour of some of her and our greatest moments in performance art (available on YouTube).

After 62 years in the field, putting her mind and body at the forefront of her interaction with the audience, one could have excused a softer touch—only her latest touring exhibition, ‘Balkan Erotic Epic’, is described as ‘draw[ing] on ancient Balkan rituals to explore sexuality, power, and liberation through immersive performances’ (BBC), with reports of women exposing vulvas and heaving, humping male bottoms doing the rounds. Surely the land of the Kamasutra deserved more of a show? In the realm of the less titillating, I could only imagine what someone like Abramović could do with theyyam, a 1,500-year-old ritual dance in north Kerala, which I had witnessed last month, wherein lower-caste men become deities through sacred, trance-like performances: with hijras and hugging ammas and the many instances of everyday exotic, in our country. Perhaps, however, given the state of the world today, the emphasis on documentation over action is understandable.

“We have to see the world like a child every morning when we wake up. We have to be fragile, strong… performance is an immaterial form of art. Everything that is left is from you.”

It is a more elevated form of spirituality that appears to move the artist in India. Abramović’s time in Bodhgaya, an arguably more marginal aspect of contemporary India that is evoked, appears to be the most influential aspect of her previous time here. ‘Waterfall’, her cascading multi-video installation of 108 monks chanting across this Buddhist-dominated landscape in the country’s northern region, offers a row of seats for visitors and a different vision of the country. When asked whether she is inspired by India today, at the press interaction a couple of hours earlier, she replied baldly: ‘No’, explaining that we often take the worst of the West and apply it here.

From Taiwanese artists with awe-inspiring endurance–Tehching Hsieh is revered by many, including Abramović–to the renowned dancer Pina Bausch, and the charming Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen), her former collaborator and partner, ‘History of Performance Art and MAI’ was full of reminders of the value of bearing witness. There is something of the eternal student, too, in the evergreen artist’s approach; later, at Anand Warehouse in Mattancherry, we witnessed a performance by British artist Hetain Patel (the multiple-register ‘Mathroo Bhasha’), where Abramović sat in the front row, clad again in white. Like many, I am watching her watching him. The focus is unwavering, except for some visible impact from the heat of our closed setting. The little fan she wields only adds to the sorceress vibe she so evidently enjoys.

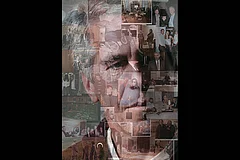

There had been a corresponding touch of drama at the press interaction. A nervous young performance artist, face painted white, seemed to have attended the biennale with the sole purpose of asking about the rumours surrounding Abramović. A desire to shock and provoke, in turn, is not an uncommon response; in the film documenting ‘The Artist is Present’, a young woman shucks off her shift dress when she sits across from Abramović on the show’s last day, in a thwarted attempt to speak her language. In Kochi, too, the young artist had a tough time making her provocation, until Abramović finally said, “Can you be more specific?”. The controversy stems, of course, from some of the viral stories connecting her to child sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman, and the paedophile ring allegedly tied to a pizzeria in Washington DC: part of the shocking fallout of the Epstein files, containing disturbing and credible evidence of large-scale sexual abuse by the world’s power elite, as well as the colourful lexicon of conspiracy theorists.

When I post from the evening on Instagram, my friend’s husband in Singapore messages immediately: “Isn’t she a witch?”–Abramović’s performance, “Spirit Cooking”, inspired accusations of Satanism. Visibly agitated, the artist spoke to what she says are dangerous misconceptions of her conceptual art. “You make a lot of mistakes in accusing me,” she tells the young artist, insisting on responding in a drawn-out exchange. “It is so dangerous for me. And there is no truth in this.”

Art has always existed in close proximity to political and socioeconomic power, of course, and the connections made between Abramović and the global super elite, however tenuous, stem from this nexus. For example, Meha Patel, ‘Gold Artist Patron’ of the KBF, is invited on stage for a part of the press interaction led by KMB curator and performance artist Nikhil Chopra, who inspired Abramović to visit the art event.

At the other end of the spectrum, I watch a bodyguard who is peering at the art at the Island Warehouse before the lecture—accompanying a platinum patron, her phone and handbag in his hands at intervals—and getting very close to the rustic mud structures of South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape (‘Mme Mmu, Bhumi Bhumi’). His is the kind of curiosity that has been a pleasure to witness at this Kochi-Muziris Biennale, particularly in India, where the class divide can be more acute when it comes to access to certain kinds of art.

“We have to see the world like a child every morning when we wake up,” said Abramović, repeating her intense mantras to the press in Kochi last week, even as she asked someone to tell her a good joke. “We have to be fragile, strong… performance is an immaterial form of art. Everything that is left is from you.”

Showing up for art is showing up for human connection, for leaving some kind of mark in an increasingly precarious world. Whether you worship at her altar or watch from afar, Abramović reminds us that this is what makes it all worthwhile.

Rajni George is a writer and editor based in south India. Her work has appeared in publications including Pleiades, The Spectator and Mint Lounge

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

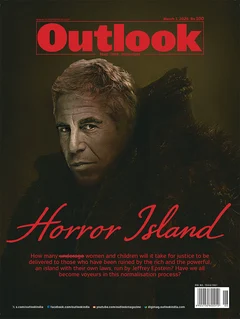

This article appeared in Outlook's March 01 issue titled Horror Island which focuses on how the rich and powerful are a law unto themselves and whether we the public are desensitised to the suffering of women. It asks the question whether we are really seeking justice or feeding a system that turns suffering into spectacle?