Summary of this article

Dhiraj Rabha uses immersive installations, film and found imagery to reveal the politics of power and history

The Quiet Weight of Shadows explores the ways power operates and narratives are constructed

The Northeast, marked by turbulence—an era of violence, displacement and silences that continue to inform his artistic inquiry.

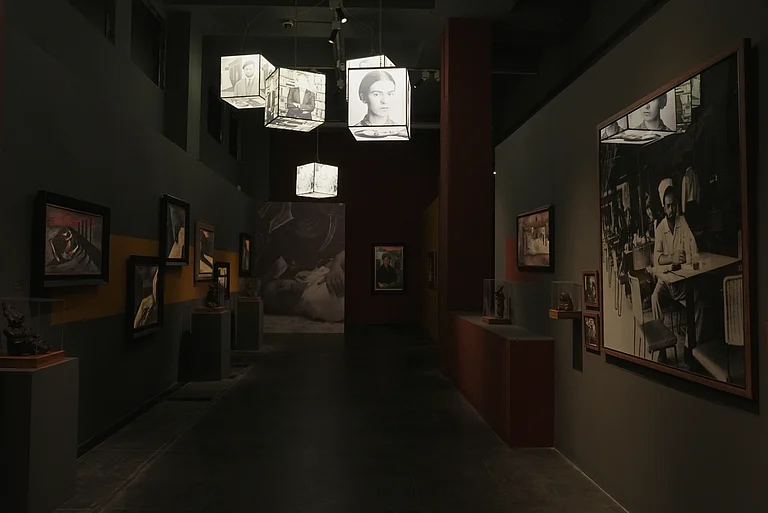

History weighs not only on Dhiraj Rabha’s works, but on his life itself. The Quiet Weight of Shadows, his installation at the Kochi Biennale, unfolds as a meditation on how history is produced and imposed—how power is exercised over communities, and how official narratives are constructed at the cost of lived realities. Drawing on memory, personal experience, and collective trauma, the work dwells on the silences and absences in the historical record, revealing the dissonance between what institutions remember and what people on the margins endure.

Looking home, from a distance

“My perceptions about my land and its history changed when I moved to Santiniketan,” says Rabha, reflecting on why history matters so deeply to his work. Growing up, he recalls, life in the rehabilitation camp at Goalpara—home to erstwhile militants of the United Liberation Front of Assam or ULFA —felt almost ordinary. “I thought our history was normal,” he says. Rabha’s father was an ULFA activist, often away in the forests, while the family lived under the constant shadow of counter-insurgency operations.

“Only now do I remember how my mother protected us,” he adds. She moved the children from one place to another, trying to keep them out of sight. With distance, he has come to understand that fear shaped every aspect of their lives; even relatives of activists were not spared.

Rabha’s work at the Kochi Biennale emerges from sustained research into the history of his land. “I want to go beyond my lived experience to arrive at a more exhaustive understanding,” he says. As a child in the 1990s, he witnessed a Northeast marked by turbulence—an era of violence, displacement, and silences that continue to inform his artistic inquiry today.

Who Controls the Narrative?

In the installation, Rabha constructs an immersive field of attenuated, almost fragile-looking plants that glow eerily in red and green. “These are carnivorous flowers,” he explains, suggesting both seduction and violence embedded within their form. Scattered across this landscape are video recordings drawn from archival interviews with former militants, their testimonies playing out as fragments of memory and lived experience from the years of insurgency.

At the same time, another set of voices travels through the installation. Emanating from the flowers are excerpts from mainstream news reports—voices that once defined the insurgency for the public and continue to shape its official memory. The coexistence of these narratives creates a deliberate tension. The flowers, visually captivating and almost inviting, relay versions of history that sit uneasily against the militants’ recollections, which are mediated through the very system installed among the plants.

“There is a mismatch between what was aired and what they actually say about their experience,” he observes. For him, this dissonance is not accidental but structural. The installation exposes how power cushions itself through language, spectacle, and repetition, smoothing over violence and fear while claiming objectivity. By placing these conflicting voices in the same space, Dhiraj foregrounds the politics of narration itself. “Those who control the narrative,” he adds, “ultimately control history.”

Alongside this, his recreation of a burnt house serves as another potent repository of memory. The charred structure carries the weight of a violent past, layered with photographs that document resistance, protests, rehabilitation camps and members of the ULFA. Together, these images function as fragments of a contested history, evoking lives marked by conflict and surveillance. Rather than offering a linear narrative, the work assembles memories that refuse closure, insisting on the presence of what has been damaged, erased or left unresolved.

Refining the Medium

At first glance, the flowers appear attractive, but upon closer examination, there are many layered histories and stories beyond the one being told. “Not only in Assam but across the entire Northeast, people are susceptible to issues of cultural, environmental, and national identity. There are many layers to it. I am trying to present that. Memory is being held against the dominant narrative,” adds Rabha. During the installation, a film titled Whispers Beneath the Ashes is projected. In this film, a group of children wandering in the forest encounter a mysterious presence. Here, the search for home is the theme, and home serves as a metaphor. The quest for home is the journey,” he adds.

A graduate in political science, Rabha says he is still in the process of discovering and refining his medium. “Through research, it is the subject itself that determines the medium of expression,” he explains. His practice, shaped by inquiry rather than form, allows history and lived experience to dictate how a work finally takes shape.

Dhiraj Rabha has previously participated in the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa (2023), was a Prince Claus Seed Awardee (2023–24), and took part in the Bengal Biennale in 2024. For him, history, the politics of power and the many-layered stories of people remain the central forces guiding his artistic practice. The medium, he insists, is never fixed—it is shaped and reshaped by the subject it seeks to articulate.