Summary of this article

Spanning 165 works, along with personal effects, awards, and photographs, the show traces an artist who lived much of his life in silence.

Among the earliest abstractionists in India, Gujral's use of material went further than that of any of his contemporaries

His portraits of national leaders—Lala Lajpat Rai, Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi—aimed to offer a psychological perspective of the subject rather than a hagiographic one

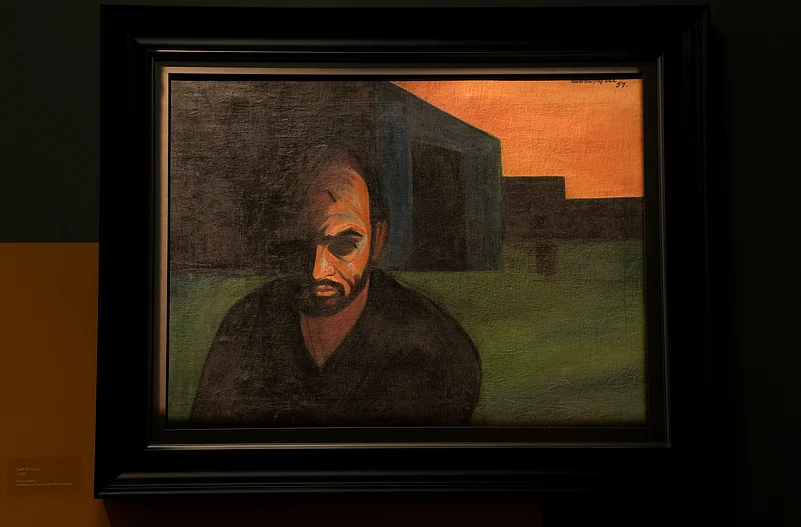

As you wander into the gallery, there’s a self-portrait by Satish Gujral that holds your gaze. A balding man with one half of his face in harsh saffron and the other half in shadow, and the contours of the face hardly visible. The bright half echoes the colour of the sky behind him. It jumps at you also because the work is placed on the wall split between dark grey and bright yellow.

The image stays with you because it is reflective of the exhibition – a life lived in between silence and turning inward and a life in light and shining brightly.

This work belongs to a group of paintings Gujral produced during his time in Mexico between 1952 and 1954. Shown within the section titled Loneliness and Strife: The Mexico Years, the works from 1952 are marked by shadows, patches of bright skies, elongated figures and severe geometric forms.

These paintings form a key part of Satish Gujral 100: A Centenary Exhibition, curated by Kishore Singh in collaboration with the Gujral Foundation at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), Delhi. Coinciding with the reopening of Gujral House in December 2024, the exhibition carries a sense of both commemoration and homage.

The opening of the exhibition is not immediately sombre. Visitors are greeted by the sound of gently flowing water, a meditative backdrop. Its significance is revealed in the accompanying text: when he was eight, Gujral slipped on stones in Kashmir’s Lidder River, and an infection left him deaf. This shaped his art and inner life and is followed by photographs of his parents, Pushpa and Avtar Narain Gujral, and a portrait of his father, grounding the narrative in memory and family.

Spanning 165 works, along with personal effects, awards, and photographs, the show traces an artist who lived much of his life in silence. Silence is a constant undercurrent and reflections and inward listening becomes evident.

After earning a 1952 scholarship, he trained under Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. In Mexico, he bonded with Frida Kahlo over their shared experiences of disability and received formal training in modern muralism, becoming the first Indian artist to do so.

Soon after, the exhibition moves towards another self-portrait: a man heavy with thought, his face wrapped in what could be a thick blanket but also layers of grey smoke. This work marks the beginning of A Dark Midnight: The Partition Series. A few of them painted in 1951–52, proved decisive. It was these works that earned Gujral his scholarship to study in Mexico. He continued to paint his memories of the partition in Mexico, and after his return.

Despite his hearing impairment, Gujral accompanied refugee convoys across the border, witnessing the aftermath of violence and displacement at close quarters in 1947. The series, from his experience during those journeys, is marked not by violence or rage, but by extreme grief, loss and quiet endurance. There are swathes of sorrow tempered by fleeting tenderness of a woman holding children close.

“He broke away from the hegemony of realist and academic painting with his Partition series. His portraits introduced a new depth. Among the earliest abstractionists in India, his use of material went further than that of any of his contemporaries,” explains Singh.

Born in 1925 in Jhelum, undivided Punjab (now in Pakistan), Gujral died in 2020. The younger brother of Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral, he began studying applied art at 14 at Lahore’s Mayo School of Industrial Arts before moving to Mumbai to specialise in painting at the Sir J.J. School of Art.

“Satish Gujral’s art is closely bound to his personal experience and ideas of nationhood,” explained Singh. “This is evident in works such as the Partition series, as well as those responding to the Emergency and the Delhi riots, which create a socio-political dialogue around history and those most affected by it.”

His portraits of national leaders—Lala Lajpat Rai, Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi—aimed to offer a psychological perspective of the subject rather than a hagiographic one, explained Singh. His abstract and pop works, along with his murals, reflected a nation searching for its roots. Their subjects were shaped by events unfolding around him. “He was a chronicler not only of India’s darkest moments,” Singh added, “but also of its achievements and triumphs.”

A painter, sculptor, muralist, architect, and writer, Satish Gujral was a modernist whose work reflected his times. While the exhibition highlights his art, traces of his architectural practice are visible.

His family resists placing him neatly within modernism. “We hope viewers reconsider him not simply as a ‘modern master’, but as an artist in constant dialogue with memory, history and resilience,” says his son, Mohit Gujral. “As audiences move through the exhibition, I hope they feel the emotional intensity and the restless curiosity that shaped his practice.”

This thinking shaped the curatorial approach. The exhibition presents Satish Gujral as an artist of wide emotional and formal range, whose work evolved continuously while remaining rooted in lived experience. Rather than fixing him to one style or period, the show traces the arc of his practice and the steady transformation of his visual language, without losing its human core. Yet, as curator Kishore Singh notes, he also represented the pioneering phases of Indian modernism more fully than almost any other artist of his generation.

Gujral did not work closely with galleries. “As an artist, he was deeply independent and never aligned himself rigidly with dominant movements or schools. That position was partly circumstantial, but it also became an intentional stance. He trusted his inner compass more than prevailing critical trends, which gave his work a singular voice,” says Mohit Gujral.

He turned to architecture when he was around 50, during the late 1970s and 1980s. The show doesn’t have those works but only has glimpses of it. Facing criticism for his lack of formal training, family accounts suggest that it prompted him to encourage his son, Mohit, to study architecture. Gujral went on to design major buildings, including the Belgian Embassy in Delhi, Goa University, palaces in Riyadh, and Modi House in Modinagar. A separate exhibition of his architectural work opens on January 31 at Gujral House.

“Over time, however, the (architectural) work earned its own validation through major projects and significant recognition. I believe he quietly revelled in such situations. They strengthened his resolve and reinforced his belief that instinct, integrity, and imagination could be as powerful as formal credentials,” added his son.

The exhibition shifts to his murals, grouped under Modern Muralism. Painted in reds and pale blues, some recall Buddhist mandalas fused with Indian motifs. Red and blue circular forms anchor the compositions, divided into quadrants with fragments of faces, numbers, signs, and textures. Additionally, there are photographs showing murals created by Satish Gujral in and around the city in Baroda House, lawns and façade of the Delhi High Court and the Shastri Bhawan.

Spread across 15 sections, the exhibition moves through distinct materials and moods. “The idea was to locate him within the personal,” says Singh. “His art emerged from a deeply felt and lived space. Gujral lived with silence. His studio was a retreat, a place of reflection. Everything he made came from there.”

In works from the Emergency (1975–77) and the Delhi riots of 1984, Gujral uses his material to channel his grief. Charred wood, burnt leather, rope, glass, cowrie shells, ceramic beads are used to register loss and they come together as abstract, god-like forms – Lord Ganesha, tridents. The darkened leather reminds one of dried blood.

Midway, the tone shifts with A Lust for Life. The works become playful, sensuous and openly celebratory. Paintings and sculptures move away from anguish towards vitality. The figures are abstract, allowing Gujral to explore desire without coyness or excess. Bulbous heads, elongated necks and entwined bodies reveal physicality. Breasts are drawn without shyness; lips are a vivid red, making it sensual.

Gujral entered a new period around 1997–98, when he began using a cochlear implant. But, he used it only these two years. His relationship with colour shifted. Palettes softened. Figures became playful and sharply drawn. Musicians appeared, their bodies often curved, echoing the shape of the inner ear, a motif shaped during long stretches in hospital as he underwent the implant procedures.

For Mohit Gujral, his father’s introspection is often overlooked. Viewers notice the scale and force of his work, but it was shaped by solitude. “The exhibition shows Satish Gujral as an artist of wide emotional and formal range, whose work evolved while staying rooted in lived experience. Rather than defining him by one style or period, it traces his artistic journey and how his visual language transformed, always keeping a human core,” said Mohit.

“Audiences see the finished works, but not the life behind them—displacement, illness, travel, literature, music, and diverse cultures. His art responded to life. The exhibition highlights these layers. We also reissued his autobiography with a new epilogue, as much of his later work followed the original edition,” he added.

Planning the exhibition took more than a year. It spans the full range of Gujral’s practice: the Partition series, the Mexico works, portraits, the Emergency and riot pieces, abstractions, love paintings, murals, metal reliefs, sculptures, icons, miniatures, late memory-based paintings, burnt wood, bronzes, textiles and drawings. Few Indian artists show such sustained shifts in style, material and approach within a single career, underscored Singh.

“There were two issues I had to consider from the outset,” says Singh. “The sheer range of his practice, and how to represent it. And access to a large body of work, and how to edit it within a limited space. Neither was straightforward. While many works came from the Feroze and Mohit Gujral collection, other family members and private collectors also lent key pieces. In addition, three museums contributed generously from their holdings: the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi; the Chandigarh Museum and Art Gallery; and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi.”

In the latter half of the exhibition are Gujral’s metal sculptures, abstract works that merge human and machine forms. These bulbous shapes draw equally from Tantra and architecture. They feel futuristic, but they were created in 1980. You either like it or don't.

Then a shift follows. As Gujral grows older, his work turns playful. Whether influenced by his grandchildren or memories of a childhood, Beastly Tales introduces horses, zebras, birds, elongated elephants and flying figures. Whimsical and light, these works throw back to a childlike imagination. The exhibition then closes with sketches of people, places and imagined structures resembling a time machine, part memory, part invention, suggesting a private world we can only see parts of.

Moving through the exhibition, it becomes evident that many of Gujral’s most important works have remained within the family. “These were often pieces that marked turning points,” says Mohit Gujral. “My father kept works that were deeply personal or signalled new directions.” Others were reacquired from galleries and auctions to complete the narrative, while extended family members also shared works from their collections.

“Crucially, my father’s architectural practice gave him financial independence,” Gujral adds. “It freed his art from the pressure to sell. That freedom allowed risk and experiment, and many pivotal works remained with the family.”

At the heart of the exhibition is a section of memorabilia from Gujral’s home. At its centre sits a sculpture that resembles an hourglass, yet not so. Around it are photographs, paintbrushes, a print of his portrait of Indira Gandhi, awards, letters and his diary. It feels real because these are objects that the artist touched and lived with and are personal. And yet, it feels surreal.