November 4 marks the 100th birth anniversary of Bengali auteur Ritwik Ghatak.

The Partition of Bengal was a strong underlying theme in Ghatak's films, as he had personally suffered its consequences.

Ghatak's Partition trilogy includes Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962).

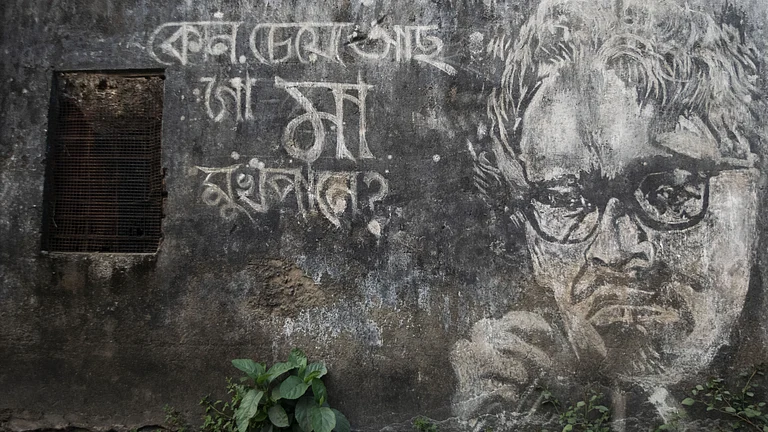

Anasua (Supriya Devi), a young theatre enthusiast, stands with Bhrigu (Abanish Banerjee), the leader of a rival theatre group, by the river Padma. Their clothes sway in the river breeze, hair unkempt. They look toward the opposite bank of a river that separates two countries that once were one, trying to locate their lost home. By now, they know that losing a home is one thing, losing its memory is another. This scene from Komal Gandhar (1961) captures the very feeling that runs through nearly all of Ritwik Ghatak’s films: that of lingering at the outskirts of belonging with a broken heart, hopelessly wondering what could have been.

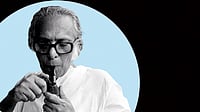

Ghatak, born in Rajshahi, Bangladesh, in 1925, migrated to West Bengal during the Partition of 1947. He knew intimately the feeling of poverty, dislocation, and loss of identity. Perhaps that is why he remains the only filmmaker to have portrayed the refugee experience on celluloid with such scale and nuance. The Partition was an open wound that marked his art, his worldview, and his sense of belonging—to the point where the fracture of his udbastu (dislocated) identity shaped every story he told. For an entire generation that formed a queue and left home with whatever they could carry, remembering was unforgiving. Ghatak knew, as only the ones who had lived through those times would.

Too radical for his times, he was; too restless and erratic to negotiate with any system; too sincere and morally upright for diplomacy or compromise; too earnest to make films that would please the affluent or even bring him money. Too dynamic to be confined by genre, he moved fluidly between forms—often collating classical music with folk songs, and the Brechtian alienation techniques of theatre with the emotional ebullience of melodrama. Above all, he was too loyal to the painful times he was living through, creating provisional characters who only sang sad songs, wrote novels and directed plays about the broken times, all while living through the grueling post-Partition years.

The Partition Trilogy: Mourning a Lost Home while Hoping to Build Another

Few works have shaped the prosthetic memory of the Partition and its aftermath as profoundly as Ghatak’s Partition Trilogy, comprising Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), and Subarnarekha (1962).

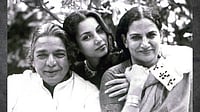

Meghe Dhaka Tara depicts the life of Neeta (Supriya Devi), a postgraduate aspirant who works as a tutor to sustain her family of aging parents, two brothers, and a sister. A father, who was once a teacher in East Bengal, now mutely watches; a mother who bitterly complains about poverty; a sister who sees marriage as her only escape; an elder brother Shankar (Anil Chatterjee), who dreams of becoming an accomplished singer and keeps asking for money from his younger siblings; a younger brother who leaves his education halfway and Neeta herself—a metaphorical star covered by the cloud of misery (meghe dhaka tara), being slowly consumed by the very cloud as she struggles to hold her family together in a new land.

Komal Gandhar centers on a theatre group that comes together to stage plays about displacement. It follows the lives of Anasua and Bhrigu—both refugees—who try to represent the sorrows of their time on stage even as they struggle with their own fractured relationship. What unites them is the shared tragedy of losing both home and family to Partition. From one side of the river, they look toward East Bengal as though mourning is the last thread tying them to their lost land.

Subarnarekha centres around the lives of Ishwar (Abhi Bhattacharya), his sister Sita (Madhabi Mukherjee), and Abhiram (Satindra Bhattacharya), a little boy he takes in and raises along with his sister. They live by the river Subarnarekha near Ghatsila, as Sita grows up with a penchant for sad songs and Abhiram with aspirations of being a novelist. Later, as they grow up, Sita falls in love with Abhiram, which creates a deep conflict in Ishwar. Ishwar’s inability to accept love across caste lines, despite his own displacement and suffering, becomes one of the film’s central tragedies.

Among other things, what connects these stories of displacement is a deep loneliness and a devastating desperation to belong that runs through all of Ghatak’s characters. They are bound by the memory of a homeland that exists only in recollection—familiar, yet forever unattainable.

The Hustle of (Un) Becoming

Despite facing the cultural snobbery of the people of West Bengal, who often complained about the refugees taking up jobs, driving up rents, and speaking a different dialect of Bengali, the refugee men and women hustled hard as though their lives depended on piecing their families back together in a new land, building everything from the ground up. Ghatak’s films capture how their lives indeed depended on it, as people often took up jobs beneath their qualifications, or even left their education halfway to help support their families.

Neeta, in Meghe Dhaka Tara, gives away all her tuition money to her family, often to help her siblings fulfill their desires. When her father loses his job, she abandons her M.A. midway and joins the office to become the primary breadwinner. Neeta’s brother Montu leaves his studies halfway to work in a factory. Ishwar, from Komal Gandhar, despite being a brilliant student, takes up a low-paying job at yet another factory in Ghatsila to support his family. Abhiram, who once dreamed of becoming a novelist, ends up driving a bus. The refugees rarely had the privilege to choose or aspire—survival left little room for either. The chasm between what one could do with one’s life and what one ends up doing only gets wider. For refugee women, Neeta being the most telling example, education did not necessarily mean emancipation. Rather, it bound them doubly to the weight of domestic labour and the economic responsibility of sustaining a home. The emotional and social realities of these characters were inseparable from Ghatak’s cinematic imagination, which carried the weight of their fractured world.

The Visual Grammar of Ghatak’s Films

A man sits under a nurturing tree, leisurely singing, while his sister bears the weight of the family, walking under the sun to reach work. Women, on their way to work, have their shoes come apart. Conversations, moments before confessions or resolutions, get interrupted by the passing train, and eventually change direction. A sister hides things under her pillow—love letters, a blood-soaked handkerchief. She must keep it all to herself. Another, out of sadness and betrayal, leaves her topor (a headgear worn by Bengali bride and groom on their wedding day) in the water of the same river that she grew up beside. When Neeta pleads, “Dada, I wanted to live” and breaks down, we see visuals of mountains and valleys, as though nature itself echoes her despair. Little Sita in Subarnarekha toes the cracked soil of a barren land, crossing sides as if to test belonging. The railway line that once connected the two Bengals, like the river Padma, now separates them. Ghatak often turns to nature to mirror the pathos of the fractured individual, which, in turn, reflects the larger rupture of society—both wounds lying beyond the reach of human repair.

When Sita sails by boat to a house in Ghatsila, someone tells her a story of a mythical home surrounded by blue mountains, with a garden full of butterflies. Years later, she tells the same story to her son. The home, once lost or rather taken by force, survives only as a story we tell to keep it alive. I cannot imagine anyone capturing the raw pulse of that separation as Ghatak did, brilliantly magnifying the cracks of the barren land that split the two Bengals and left us ruined forever. His cinema, thus, stands as an archive of loss, dutifully reminding us that every fracture, when looked at closely, holds the memory of what once was whole…what once was home.