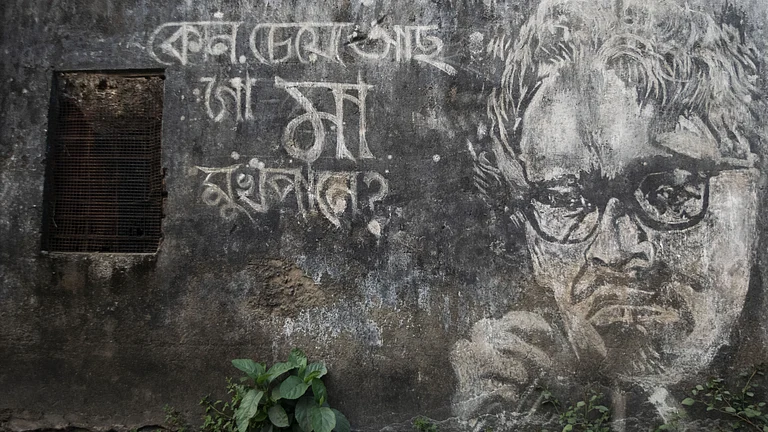

Qissa (2013) director Anup Singh pays tribute to his mentor Ritwik Ghatak.

Singh's debut directorial, Ekti Nadir Naam (The Name of a River, 2001) was inspired by Ghatak’s Indo-Bangladesh co-production Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (1973).

In contrast to Ghatak’s tidal wave of emotions, Singh’s screen sojourn is gentler, even though the pain of loss and separation is just as searing.

It was in 1983, when he joined the FTII, that Anup Singh was introduced to the cinema of Ritwik Ghatak, who had died seven years earlier. The director of Qissa (2013), who was born in Tanzania, Africa, had moved with his parents to Mumbai, India, when he was 12 and had grown up with a sense of homelessness. “Ritwik da’s films unnerved me with their assertion that we are all homeless…refuges…yet paradoxically, they also made me feel at home,” he muses.

Singh believes that it was the legendary filmmaker challenging how we understand and accept a story that made him feel this way. “The story, for Ritwik da, was not bound by a predetermined structure or a system that conceals a society’s values. It was not a plot developed to highlight a theme. It was a juxtaposition of images and sounds, that, like the river, was in a state of constant flux, challenging all boundaries,” he explains.

Titash Ekti Nadir Naam (A River Called Titas), a 1973 pre-Independence tale of love and loss, marriage, motherhood and a search for identity, journeys with a fishing community, with Ghatak appearing on screen as a boatman. “I was devastated after watching it. Titash Ekti Nadir Naam changed me as a person,” admits Singh, whose debut directorial, Ekti Nadir Naam (The Name of a River, 2001), almost 30 years later, was inspired by Ghatak’s Indo-Bangladesh co-production, even borrowing his hyperlink style of multiple protagonists and interwoven narrative threads.

Ekti Nadir Naam, a 90-minute docu-drama—screened at the recent Kolkata International Film Festival as a tribute to Ghatak in his centenary year—is as fluid and sublime as the auteur’s cinema. It’s a meandering odyssey through history and mythology, literature and cinema. It unfolds as a love story, which is sometimes real and sometimes surreal, sometimes literary and sometimes celestial, with remembered scenes and dialogues from his mentor-muse’s films, set against the Partition. Singh is quick to remind you that Bengal has lived through not one, but three Partitions.

In 1905, the ruling British divided the state into East Bengal for the Muslims and West Bengal for the Hindus, purportedly for administrative purposes, but also to quell a rising nationalist movement.

While this was undone six years later, the Partition in 1947, which resulted in the massacre of half a million people and the forced migration of another 10 million, was permanent, dividing not just the state, but even the country along communal lines.

Ghatak himself suffered the pain of displacement from which was born his Partition trilogy—Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961) and Subarnarekha (1965). “These films not only talk about the loss of a home, but also reiterate that sometimes you don’t have a home even when you are living within the family,” says Singh, pointing to Neeta’s mother in Meghe Dhaka Tara, who sacrifices her elder daughter for the survival of the family, even as her elder brother, Shankar, while distressed by what he sees happening, can do nothing to protect the girl except break away.

Fortunately for Singh, his mother and two sisters pulled him into their world, never making him feel like an outsider because of his gender, and helped shape the man he has become. “I come from a Sikh family, and till the age of 25, I had hair that fell to my knees. Every Sunday, my mother would wash my hair, and that of my sisters. We would then sit in the sun, drying our hair together. After a while, my mother, having washed her own hair, would join us on the terrace. Those memories and conversations, my relationship with these three wonderful women who gave me unconditional love and respect, made me see the world in a larger perspective, through their female gaze, which is mirrored in my films,” he shares emotionally.

There was a third Partition in 1971, when East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan, and with India’s help, a new nation, Bangladesh, was born. “Ritwik da’s camera documented this period of turmoil and trauma too—the wide-angle lens he used bringing the world into his frames so the viewer sees not just what is in front of him, but what was left behind and what is to come,” explains Singh, as metaphorically, we sail down the Padma, that becomes the Ganga as it crosses into India, continuing its journey, uncharted and unfettered.

“Like the women, the river too is a leitmotif in Ritwik da’s film—a gushing, pulsating force, which sweeps aside boundaries and borders, which won’t let you drown in nostalgia, but relentlessly carries you forward. Charaiveti, Charaiveti –keep moving on,” Singh murmurs the vedic mantra. He adds that as you travel with it, you meet and mingle with people of different civilizations, embracing their joys and pain, sharing yours with them, and in the process, the individual is erased and a multiplicity of cultures, which is India, and a multiplicity of memories, which is us, is created.

His words, soft and hypnotic, take you back to the film you have just seen in Kolkata’s Sisir Mancha. In contrast to Ghatak’s tidal wave of emotions, Singh’s screen sojourn is gentler, even though the pain of loss and separation is just as searing. Acknowledging this, he smiles, “Ritwik da did the tandav on screen, I prefer the lasya, feminine, gentle and graceful, which Parvati performed for her fiery consort. In fact, my diploma film at FTII, also a tribute to Ritwik da, was titled Lasya. After seeing it, the British Film Institute (BFI) approached me to make a film on Ritwik da, and Ekti Nadir Naam was conceived.”

With NFDC (National Film Development Corporation of India) joining hands with BFI as production partner, the film started in 1989 in Bangladesh. “After shooting for just two days, I fell ill. It must have been the water because every couple of days, there would be a relapse and I had to be rushed to the hospital,” Singh recounts.

Eventually, the doctors told him his liver was completely damaged from all the alcohol he had been consuming. “I didn’t even drink back then, but they refused to believe me. My unit insisted Ritwik da’s ghost had entered my body,” he laughs, admitting it took great resilience to complete the film as the BFI shut its production office and NFDC followed soon after.

With no support, Singh could not continue with the post-production. “Work only resumed when NFDC was resurrected and the film was completed only in 2001,” he informs. Since then, it has been screened at over 30 film festivals across the world and won several awards.

Singh’s journey with Ghatak however doesn’t end with Ekti Nadir Naam. Late at night, sitting in the almost deserted lounge of Hotel Taj Bengal in Kolkata, jet lagged from having just flown in from Switzerland, he reveals that his mentor, who died prematurely at the age of 50, left behind many scripts. “A producer, who had bought the rights to one of them, approached me to direct the film. I saw it as a gift that had come directly from Ritwik da himself and excitedly started working on it. But then, the producer realised that because of the time and backdrop, it would cost a lot to make the film, and felt that today, there may not even be an audience for it. So, despite my impassioned arguments, he shelved the project,” he laments.

But all is not lost. Singh, who has been struggling to make a film for the past three years, is hopeful that by the end of this visit to India, he will be able to green-light it. “It can only be made in Bengali, a language I learnt to understand Ritwik da’s films better and I found great joy in it and made Ekti Nadir Naam. Now, after all these years, I will be returning to it and it feels like a homecoming,” he signs off with a smile.