Summary of this article

Bengali cinema stalwart Mrinal Sen passed away on December 30, 2018.

Among the many crises in the decades he lived through, Sen’s career was forged in the fires of famine, displacement and political upheaval.

It is his dogged refusal to detach himself from his historical moment that gives his cinema its urgency.

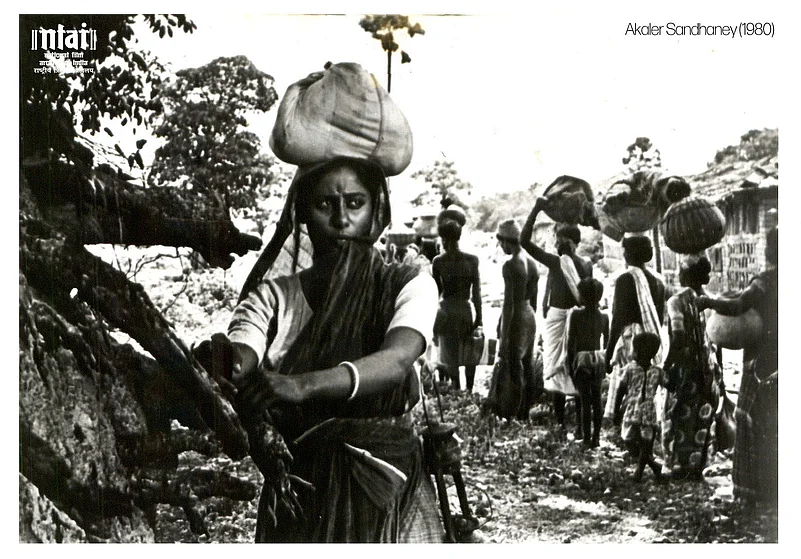

The production of a film gets postponed due to incessant rain in a village called Hatui. Stranded, the lead actors, production managers and director pass the time with a game in Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane (1980), a film that stages a film within itself. The rules of the game are simple: the actress (Smita Patil) produces photographs of hungry, haggard, skeletal bodies and the others must guess which famine they belong to and the year in which they were taken. The stack of images—from the Bengal Famine of 1943 to the food crisis of 1959 and finally to photographs of starving people from 1971—turns into a grim form of rainy-day entertainment.

This particular scene, on closer inspection, not only suggests how all starving bodies begin to look alike, regardless of what caused the hunger, but also how privilege and distance from suffering render others’ pain almost harrowingly muted, to the point where one catastrophe can be mistaken for another. Or perhaps it gestures toward something more sinister—that suffering bodies merely change generations as oppressors change their robes. The interpretations are necessarily layered. Such is the genius of Mrinal Sen, for whom political intervention was never separate from his storytelling.

Among the many crises that scarred the decades he lived through, Sen’s career (1955–2002) was forged in the fires of famine, displacement and political upheaval. A refugee from Faridpur, Dhaka, he witnessed the Bengal Famine of 1943, the Partition of 1947, the Tebhaga movement, the Naxalite movement and the 1971 refugee crisis, along with a strangulating starvation that clung to the nation through its formative years. The famine was no accident; it was the outcome of colonial wartime policies compounded by administrative neglect. When Japan occupied Burma in 1942, rice imports to undivided Bengal were cut off. As British authorities confiscated boats carrying rice stocks, wartime inflation surged and unchecked hoarding rendered food inaccessible to the poor. Millions, dependent almost entirely on rice, starved; nearly three million died in a historic tragedy that could have been avoided. This moral collapse returns repeatedly in Sen’s cinema, with Baishey Shravana (1960), Calcutta 71 (1972) and Akaler Sandhane (1980) standing as testaments to hunger and the erosion of social responsibility.

Baishey Shravana: Hunger in the Household

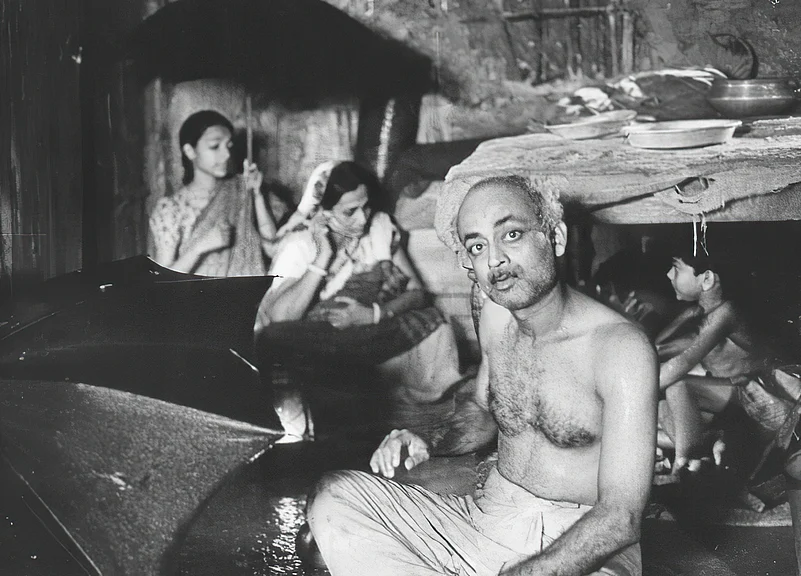

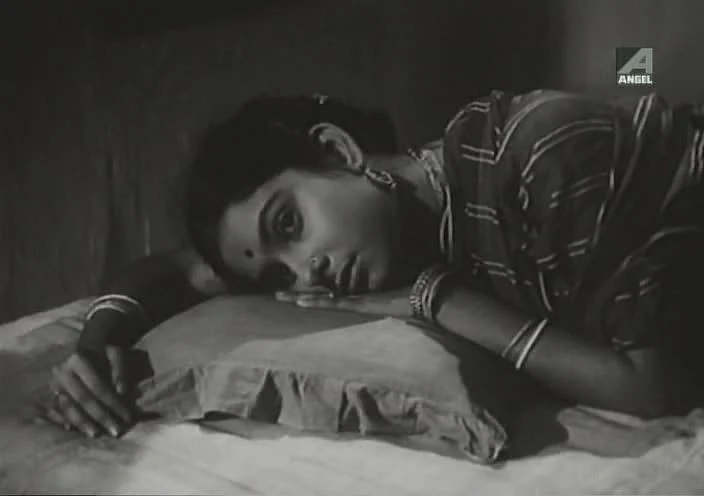

In Baishey Shravana, Priyanath (Gyanesh Mukherjee), a descendant of a zamindar family now reduced to selling cosmetics to women on trains, marries Malati (Madhabi Mukherjee), a much younger woman raised as an orphan in her uncle’s house. Years into their marriage, a storm devastates their village, destroying their home and killing Priyanath’s mother, leaving him shattered. Soon after, he gets injured and loses his job, just as famine bears down on Bengal and Orissa.

Hunger seeps into every corner of the household: it corrodes relationships and drives Priyanath to lash out at his wife, who has been quietly starving to save rice for him. The film traces the intimate devastation of one family, a microcosm of millions caught in the slow, strangling grip of starvation.

Calcutta 71: Starvation and Moral Ruin

In Calcutta 71, where Sen documents political unrest and exploitation, one of its episodic segments centres on Shovana (Madhabi Mukherjee), a recent widow living in abject poverty with her mother and two siblings, struggling to survive. Set against the backdrop of the Bengal Famine, survival marked by indignity and sexual vulnerability becomes a daily negotiation for Shovana, a single woman who is earning for her family. Sen exposes how the famine collapsed ethical boundaries, often forcing the poor women into impossibly cruel choices.

Akaler Sandhane: Reconstructing Famine

Akaler Sandhane (1980) follows a film crew that arrives in a village to shoot a film on the Bengal Famine of 1943. As the crew reimagines scenes of starvation and suffering, the line between past and present becomes blurry. The film unit ends up recreating the very conditions that made famine possible in the first place. Here, Sen turns his camera inward, questioning whether political cinema can ever bear witness to suffering without (unwittingly) reproducing the very exploitation it intends to critique.

Hunger on Celluloid

It is striking how Sen deploys different cinematic strategies to portray hunger and suffering across all three films. In Baishey Shravana, Priyanath’s love and affection for his wife are expressed through small, tender gestures such as bringing her alta (a traditional red dye used by women to colour their feet and hands), taking her on outings, or buying her favourite plant. Later, driven by hunger, he sells her jewellery, berates her and accuses her of misplaced attention—a cruel contrast to his earlier tenderness. Hunger and helplessness irreversibly corrode relationships, as the famine tightens the noose around the household. Intercut with this domestic unravelling are images of hungry children weeping on the streets and businessmen smuggling rice under the cover of night that intensify the tragedy of a middle-aged, disabled man reacting violently as his life slips beyond his control.

In Calcutta 71, Sen becomes more brazen in his political messaging. The film’s four segments are separated by a declaration: “I have been walking for a thousand years in the throes of poverty and death. For a thousand years, I have been seeing the history of poverty and exploitation.” Sen starkly contrasts footage of people dancing in discotheques with photographs and paintings of starving bodies awaiting death, collapsing pleasure and deprivation into the same frame.

In the second segment set in 1943, Nalinaksha—a privileged officer from Delhi—travels in search of his cousin Shovana and her family. On the train, a stranger (played by Bijon Bhattacharya) explains to him the four stages of famine: first, people beg for food; then for cooked rice; next, for rice water; and finally, there is only the sound of weeping and wailing. When Nalinaksha, an outsider, encounters Shovana and her aunt, their conversation is repeatedly interrupted by voices from outside pleading for some fyan (rice water), turning the private domestic space into a site of collective suffering. Sen repeatedly breaks away from narrative continuity to insert photographs and footage of starving bodies, often zooming in on them mid-scene—an intrusive political gesture that forms the spine of his filmography rather than being a mere stylistic choice.

Much like Calcutta 71, Akaler Sandhane approaches the famine through the gaze of an outsider who did not endure the crisis directly, but attempts to look into the lives of those who did. The film follows a crew trying to reconstruct the famine using texts, documents and archival material gathered during their research. The opening credits roll with Hei Samalo Dhan, composed by Salil Chowdhury in the aftermath of the famine and the Tebhaga movement—a song voiced from the perspective of farmers who refuse to surrender their paddy, no matter the cost. Right after the opening credits, a villager retorts, “City people have come to record the famine that is written all over us”—a moment that powerfully suggests how the famine’s aftermath continued to haunt rural life even as late as 1980. Later, when the production manager hoards a large amount of food to feed the crew from the small village market, a passerby mentions how the crew, while capturing the famine, has inadvertently created one in the village.

Mrinal Sen has often been criticised for turning his films into a political mouthpiece at the altar of filmmaking. Yet for Sen, cinema could never be alienated from the society it claimed to mirror—a society mired in the throes of political turmoil. His characters frequently break the fourth wall or slip into direct address, questioning their circumstances and, at times, hurling diatribes at the world they inhabit. This impulse echoes Sen’s own assertion in an interview: “I cannot pull myself out of the atmosphere I grow in, I weep in.” It is his dogged refusal to detach himself from his historical moment that gives his cinema its urgency, leaving behind a searingly honest documentation of decades marked by devastation, famine, and ruin.