Summary of this article

January 14 marks legendary poet Kaifi Azmi's 107th birth anniversary.

To read Kaifi Azmi today is to encounter a body of work that treats care as both a moral and poetic practice.

Even in despair, he stubbornly sings of hope, often through changing regimes, historical silences, and heartbreaks without closure.

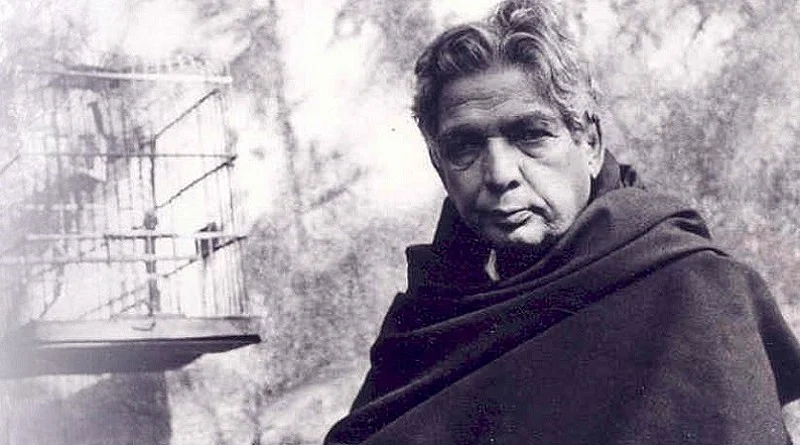

There was an Indian poet born in 1919, whose pen bled in Urdu for decades, dreaming of change—even when he knew he might not live to witness it, as he once told his daughter. In commercial Hindi cinema, he lent his words to songs that persistently captured the human pathos of existing in a consumerist world that offers the individual very little respite. Gloom followed his writing everywhere, but only as an extension of the turbulent times he lived through.

Poet Kaifi Azmi, born in Mijwan on January 14, could therefore write a ghazal that admits:

Itna to zindagi mein kisi ki khalal pade

Hansne se ho sukoon na rone se kal pade

Jis tarah hans raha hoon main pi pi ke ashk-e-gham

Yun doosra hanse to kaleja nikal pade.

(Let life trouble someone just enough/ That laughter offers no comfort, and tears no reprieve; / The way I laugh now, swallowing my grief, / If another laughed like this, the heart would give way.)

In 1979, while filming a student project about him at FTII directed by Raman Kumar, Azmi was asked why he chose to remain in India after the 1947 Partition—why he had not moved to Pakistan with the rest of his family. He was caught unawares by the audacity of the question as the camera zoomed in on his face. To me, who was watching this moment decades later, this moment stood as a reminder that Indian Muslims have long been expected to repeatedly prove their loyalty and allegiance to the nation, a demand with a cruel lineage of its own. Azmi was no exception, yet he carried his care for the nation he had placed his hopes in into his words, writing verses for workers, women, lovers—anyone in need of steadiness against the forces that hemmed them in.

Verses for the Worker

Azmi, who lived in a commune and worked for a meagre stipend to support his family by writing a poem every morning for the daily newspaper, was not writing about the poor worker from a vantage point of privilege. He was one. Thus, he could write the poem ‘Makan’ from the perspective of a labourer who has toiled and worn himself out building a house—only to find that, once the building is complete, a guard has been placed to keep people like him out. So, he sleeps in the heat on a footpath, longingly looking at his creation and hoping to find an open door that will let him in. He writes:

“Apni nas-nas mein liye mehnat-e-pahem ki thakan,

Band aankhon mein isi kasr ki tasveer liye,

Din pighalta hai isi tarah saron par ab tak,

Raat aankhon mein khatkati hai siyah teer liye.”

(Every vein bore the fatigue of tireless labour, / In closed eyes, we carried the image of this palace, / The day still melts on our heads in the same way, / The night pricks the eyes, carrying black arrows.)

His care for the workers also becomes evident in other songs, such as “Baharein Phir Bhi Aayengi” from the movie of the same name. Through the metaphor of a garden, the song asserts:

“Badal jaye agar mali, chaman hoga nahi khali

Bahaarein phir bhi aayengi”

(Flowers will grow in the garden, even if the gardener changes). Herein lies Azmi’s conviction that bahaar (Spring; but in this context, change) is as inevitable as flowers blooming in a garden, regardless of the changing gardener, authority, or regime. It is a reminder that someone must keep hope alive, and sing of it too, through the tenure of all different gardeners.

Verses for “Aurat”

Azmi’s verse "Aurat" keeps showing up on our social media feeds to date, mostly around International Working Women’s Day. This searing verse, written in the 1940s, is an invitation for women to take on an equal role and join in the battle to change the world as he writes:

“Qadr ab tak teri tareekh ne jaani hi nahin

Tujh mein sholey (burning embers) bhi hain bas ashkfishaanii (tears) hi nahin

Tu haqiqat bhi hai dilchasp kahaani hi nahin

Teri hasti bhi hai ik chiz javaanii hi nahin

Apni tareekh kaa unvaan badalnaa hai tujhe

Uth meri jaan mere saath hi chalnaa hai tujhe.”

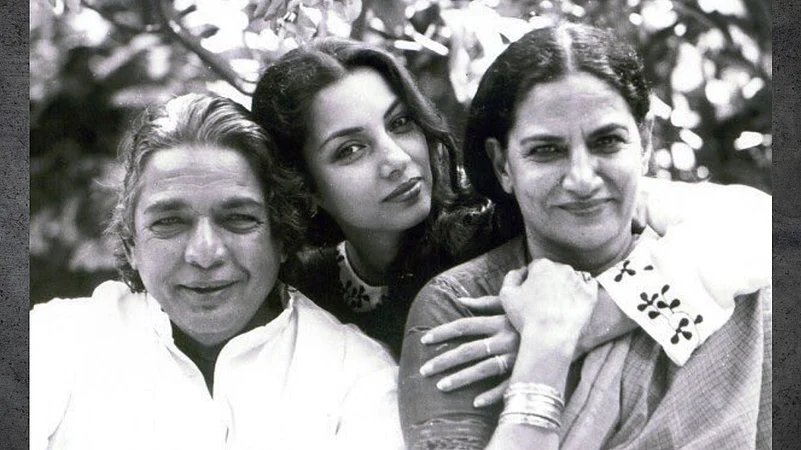

Shabana Azmi, his daughter with theatre actor Shaukat Kaifi, later recalled that gender roles in their household were reversed from the very beginning. Her father stayed at home while her mother went out to work, and Kaifi Azmi, in this sense, practised at home what he articulated in his writing.

Years later, when Azmi wrote the lyrics for Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth (1982), the film in which Shabana plays a woman who discovers her husband’s infidelity and attempts to reclaim the meaning (arth) of life after betrayal, his verse once again articulates feminine interiority. Sung by Jagjit Singh, the song renders her turmoil for the audience:

“Tum itna jo muskura rahe ho, Kya gham hain jisko chhupa rahe ho?

Aankhon mein nami, hasi labon par, kya haal hain, kya dikha rahe ho?”

While discussing feminine interiority, one must note Azmi’s lyrics for the song “Chalte Chalte” from the film Pakeezah (1972), which capture the stigma and silence a courtesan endures to eke out a living. He writes:

“Jo kahi gayi na mujhse woh zamana keh raha hai

Ke fasana ban gayi hai meri baat talte talte”

(What I could not bring myself to say, time has said for me; my words, deferred again and again, have turned into a tale). In giving voice to what remains unsaid, Azmi’s care lies in acknowledging not only women’s suffering, but the long histories of silence that shape their inner lives.

Verses for the Lovelorn Aashiq

While Azmi did write songs about reciprocated love—“Tum Jo Mil Gaye Ho Toh Yeh Lagta Hai Yeh Jahaan Mil Gaya” being a notable example—it is the torment of lovers that he elevates most powerfully through his excoriating poetry. My favourite among these is a song from Naqli Nawab (1962), which asks: “Tum poochhte ho ishq bala hai ki nahin?

Kya jaane tumhe khauf-e-khuda hai ki nahin hain?”

Or consider “Main Yeh Sochkar” from the film Haqeeqat (1964), where he writes:

“Main yeh sochkar uske dar se utha tha,

Ki woh rok legi, mana legi mujhko,

Hawaon mein lehrata aata tha daaman,

Ki daaman pakad kar bitha legi mujhko.”

These lines capture the yearning of a lover whose last hope of being welcomed into the beloved’s life slowly comes apart. Azmi’s care here lies in allowing the lover to remain vulnerable between longing and loss.

This attentiveness to emotional aftermath can also be found in “Jaane Kya Dhoondti Rehti Hain” from Shola Aur Shabnam (1961), where his verse lingers at the threshold of accepting heartbreak:

“Ab na woh pyaar, na uski yaadein baaki

Aag yun dil mein lagi, kuchh na raha, kuchh na bacha

Jiski tasveer nigaahon mein liye baithi ho

Main woh dildaar nahin, uski hoon khaamosh chita.”

To read Kaifi Azmi today is to encounter a body of work that treats care as both a moral and poetic practice. He focused on those often written out of literature—the poor, the wounded, the displaced, and the heartbroken—and wrote verses that allowed fatigue, longing and hope to coexist. Whether it is the labourer locked out of the house he built, the woman whose truth is trampled, or the lover suspended between love and longing, Azmi’s words remain anchored in lived experiences, always holding space for hope. Even in despair, he stubbornly sings of hope, often through changing regimes, historical silences, and heartbreaks without closure. In doing so, he leaves behind a legacy of care and attentiveness, all while dreaming of tabdeeli—the change he believed would arrive.

Sritama Bhattacharyya has an M.Phil in Women’s Studies from Jadavpur University, Kolkata. She is currently an English Teacher based in Washington.