Summary of this article

Anjan Dutt’s work has always been an act of documenting the “other.”

He writes about a cosmopolitan Calcutta Where Satyajit Ray could be seen browsing books from the city’s pavement shops

Mrinal Sen was like a father figure for Anjan Dutt, he says

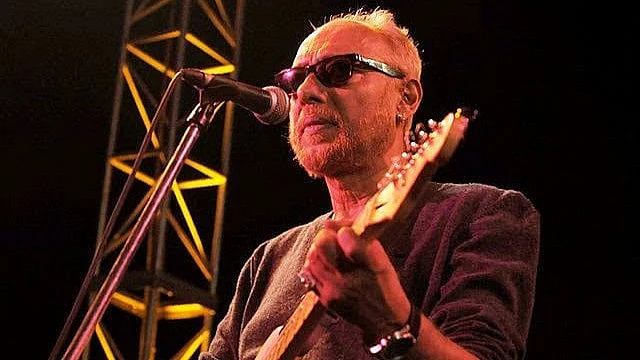

For a generation of Calcuttans who grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s, Anjan Dutt was less a celebrity and more a cartographer of their internal lives.

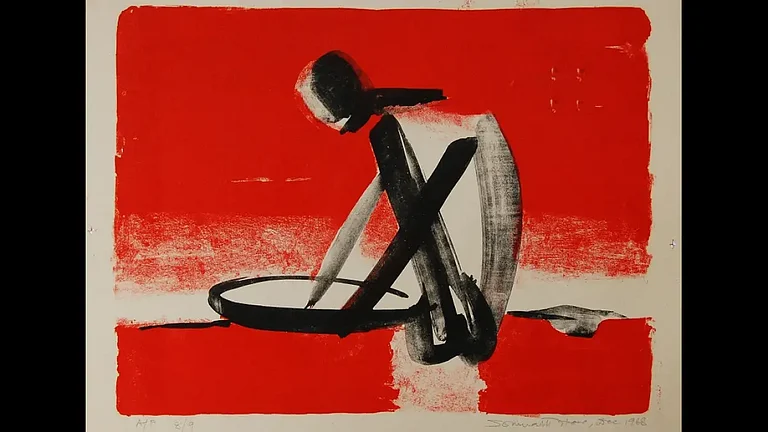

Dutt’s work has always been an act of documenting the “other.” Whether through the hippie-tinged nostalgia of ‘Madly Bangalee’ or the claustrophobic family dynamics of ‘Dutta vs. Dutta’, he has consistently pivoted away from the state-sanctioned history of the city to focus on the marginal. One can still find the characters from Anjan’s songs or films at Kolkata’s flower markets, Babughat or during Christmas at Bow Barracks. He came to tell the story of that cosmopolitan Calcutta Where Satyajit Ray could be seen checking vinyls or books from the city’s footpath, Badal Sircar would descend upon the Moulali crossing to perform his Third Theatre, and Mrinal Sen would lie down on the Red Road to frame a shot. The story of the quintessential madly bengalis, who were as comfortable with a jhola bag on a North Kolkata fishmarket as they were with a Leonard Cohen record.

Now, at 73, Dutt is performing his most intimate act of storytelling yet. His latest offering, the memoir, ‘Anjan Niye’(Dey’s Publishing), is an intimate look at this life. From the misty Mall Road of Darjeeling to the chaotic streets of Calcutta, the book traces the theatre, the music, the films and the many lives Dutt has lived within a single existence.

In this conversation, Abhimanyu Bandyopadhyay speaks with the veteran auteur about his book, the city he can’t stop rewriting, and why, after all these years, he’s finally ready to tell the story of “Anjan.”

You’ve been writing detective novels for years and even made a series and a film on your own character. Why suddenly decide to write a memoir?

Anjan: I never had a burning desire to write a memoir. My publisher, Apu (from Dey’s), had been chasing me for five years to write something personal. I kept dodging him because I was more interested in writing my detective, Subrata Sharma. I’ve always felt Bengal lacks gritty, modern detective fiction. Eventually, in 2022, my book Danny Detective INC was published. By mid-2023, after delivering four books to them, I realised I couldn’t keep turning down their requests. Also, I feared that if I waited longer, I’d lose my intellectual objectivity. With age, uncontrolled emotions can lead to unnecessary rambling, and that spontaneous sense of fun might diminish. I also realised I was starting to mix up dates and years, so I didn't delay any further.

Did those detective stories help in writing your memoir?

Anjan: Massive help. Beyond the royalty cheques and some recognition as an author, those stories gave me a specific style of writing. I’m 73 now; I’ve made mistakes, but I’ve always tried to do something different, beyond the binaries of right and wrong. That’s why my theatre, films, and music are all very stubbornly 'Anjan'. It annoys some, but I think my audience loves me for that very reason. Danny Detective INC gave me the space to find that personal expression in writing.

At the start of the book, you describe your life as a "grand circus", full of fun. Do you feel the innate Bengali ability to laugh at oneself or make others laugh is gradually fading?

Anjan: It’s practically extinct. From eight to eighty, everyone has become so... beroshik (humorless). The hallmark of the Bengali character was a sharp, modern sense of humour—the ability to mock oneself effortlessly. Unfortunately, we are losing that. Nowadays, everyone has become so "politically correct." Everyone is measuring everyone else. I’ve always believed that a person who cannot joke about themselves cannot make a decent film. Take a look at our ads or plays today; that witty intellect is gone. We are the descendants of Sukumar Ray, for god's sake! Why is everyone so serious? Without that sense of fun, my or Suman’s [Chattopadhyay] lyrics would never have happened.

Is it just a loss of humor, or a general socio-economic decline over the last few decades?

Anjan: Look, Bengalis never had much money, but we had a cosmopolitan instinct which was once an integral part of our collective unconscious. We lived in narrow lanes like Beniapukur but felt like global citizens. If the Beatles dropped an album in London in September, we were listening to it in Kolkata by December. Very few cities had that urge to connect with a global soundscape at their own expense. Where have those people gone? Instead, some strange defeated mindset took over everything. This sorrow-stricken city is not my Kolkata. I’ve seen magnificent 200-year-old British buildings demolished. Grand statues replaced with ugly ones. Street names changed. Witnessed the historic Statesman House become a shopping mall. Kolkata's Cultural decline didn’t start yesterday, it began long ago by those in power. Yet in this same city, Satyajit Ray’s 'Feluda' once declared that he would go on hunger strike if New Market was demolished. That street-fighting spirit is now gone. I don't know about others, but If they rename Park Street tomorrow, I will go on a hunger strike. I can’t let that change.

You’ve mentioned how a healthy economic exchange once shaped the city's culture.

Anjan: Exactly. Until the late 80s, most major corporate headquarters were in Kolkata. So, educated Bengalis looked for jobs here, not in Delhi or Mumbai. Even the wealthy class here was immensely culturally minded; they didn't just invest in stocks. Take Shyamanand Jalan, a pioneer of Hindi theatre in Kolkata and a wealthy lawyer. He let me do my first musical show in his space for free. I’ve never heard of a Gujarati lawyer practicing serious theatre in Gujarati like that. Pritish Nandy, editor of The Illustrated Weekly, wrote brilliant English poetry that Shakti Chattopadhyay translated into Bengali. The elite’s taste trickled down to the middle class. Reading a good book, watching foreign films, and listening to classical music became part of their daily life. That cultural influence is why a government clerk would still go to the theatre once a month or buy a new record. That middle class later ran little magazines and theatre groups.

Has that cultural consciousness been swallowed by mediocrity?

Anjan: Media and advertising are the yardsticks of a society’s quality. In the 70s, Kolkata produced Junior Statesman, a dynamic fashion magazine. How many Indian cities did that at that time? Think of the film societies—Bengalis middle class waking up early to watch Polish or Russian films at the film clubs. Can you imagine that level on enthusiasm today? The post-90s generation didn't get to witness any of that. They grew up on imported culture. Today, advertising is just celebrities selling cement or flour. Taste has deteriorated drastically.

You wrote about seeing Satyajit Ray and many other international personalities buying books or vinyls on Free School Street. Has the bond between artists and the streets weakened?

Anjan: They were on the streets because they had to be—to haggle for books, buy records, or do the groceries. They didn’t sit inside homes decorated like Airbnbs all day. Do today’s celebrities feel that need to be on the street? I don’t know. Everything feels a bit too polished and ‘perfect’ now. I miss that bohemian spirit.

Maybe it’s just my problem, but I personally can’t leave these damp-stained walls, this garden, and my messy room to spend my life in a 3bhk flat in New Town. Even though I have a car, I still use the bus. If I need to go somewhere nearby, I just hop on a bus and get off—it saves money, too. We still get our daily groceries from the local market. So, I never thought it was abnormal for a director or a musician to ride a bus, shop at a roadside market, browse books at College Street, or walk to the local shop for a pack of cigarettes. I don’t believe in any celebrity lifestyle.

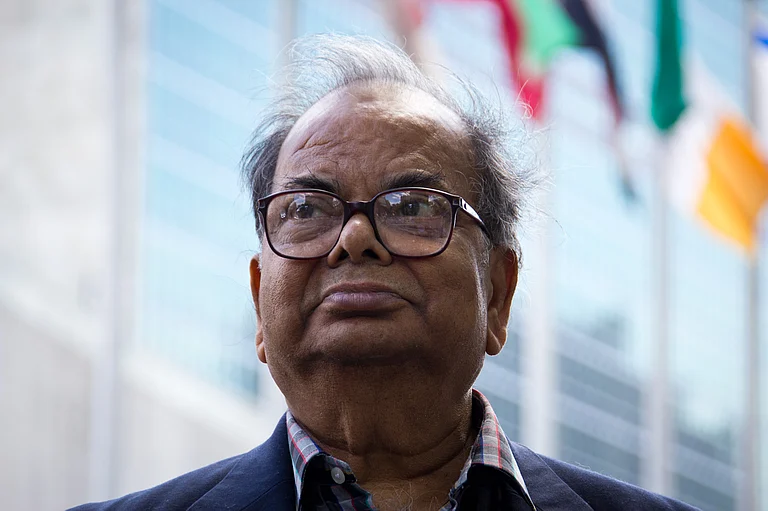

From adolescence to youth, your life seems to have been surrounded by a remarkable father archetype. In Anjan Niye too, those fatherly figures keep returning again and again in various contexts.

Anjan: I don’t know why, but maybe because of my crazy, argumentative nature, seniors were always very fond of me. Maybe deep down, I was always searching for a father figure. Mrinal Sen was closer to me than my own father. I could talk to him about things I never told my dad. These men didn't let me lose. Every time I broke down in life, they pushed me forward. I wrote in the book that I have a Bael (wood-apple) tree in my garden. Sometimes at night, I feel like Hardeep, Badal (Sircar), Mrinal, Tancred—they’re all sitting up there, watching over me.

While writing about Badal Sircar and Mrinal Sen, you often referred to them as “my Badal” and “my Mrinal.” Does that come from a kind of filial sense of belonging?

Anjan: Partly, yes. Every relationship I have is deeply personal and intense in nature. I don’t maintain any casual connections. I only keep relationships where I could speak my heart, be shameless, cry, disagree and be vulnerable. My relationship with my father was very problematic, but towards the end of his life, we somehow had an intense connection between us. For that short period of time we became very close to each other. That’s why I don’t have a million friends, but the few I have are deeply personal. Badal Sircar and Mrinal Sen has always been two major phenomena in my life. Nobody impacted me more than these two mavericks. Badal Sircar taught a 23-year-old Anjan how to see the city and its people. He pushed me to realise my potential. Even though my time with him wasn't as long as with Mrinal, he stayed in my thoughts throughout. That’s why I could say “my Badal,” “my Mrinal" with such sense of ownership.

You have also written that you experience a peculiar “withdrawal syndrome” in relationships.

Anjan: Yes. When the mutual exchange ends, the relationship ceases to exist for me. Despite loving Badal Sircar, I couldn't accept his 'Third Theatre' philosophy. I didn't want to argue with someone I loved, so I moved away.

I don’t go to film premieres because if a movie is bad, I can’t lie about it. I avoid weddings because I won't recognize most of the relatives. I still hate picking up the phone. But I’ve never disrespected anyone. I just move away. People might think I’m an arrogant , rude person, but I can’t maintain a connection just for social etiquette. I’m grateful to my wife and son; whatever social links I have left are because of them.

Do you think that by 2026 there has been an increase in intolerance toward opposing opinions, food habits, and political beliefs?

Anjan: Intolerance was always there. The Left front government had shut down my plays multiple times calling them obscene. Halls were denied to Kabir Suman too. But with smartphones, the intensity has skyrocketed. We can't handle minor disagreements anymore and turn to vulgarity. I’ve written clearly that Shambhu Mitra’s theatre didn't appeal to me, but that doesn't mean I disrespect him or those who love him. Mrinal Sen loved Shambhu Mitra’s theatre, yet he could appreciate me, even though I did the opposite. We were polar opposites in politics and upbringing, yet there was mutual respect. I once studied Marxism a lot. Not to become a Marxist, but to know something new. At 18 I first read Che Guevara’s bolivian diaries just because that man looked so damn good on the cover! There was no communist hangover. That space to accept a different view is shrinking

Recently, in your city, a vendor was attacked for selling nonveg, also there was another controversy over beef being served at a well-known restaurant. Does it upset you to see the Kolkata you knew changing in this way?

Anjan: There is a persistent, ugly attempt to change the soul of this city. It is shameful. Kolkata’s food scene is as vibrant as the city—Chinese, Parsi, Lebanese, Korean, Burmese... where else do you find this? I’ve seen the world, and no city adopts other cultures and food habits like Kolkata. Today, a segment of society has become strangely insular. If in 2026 we still argue about who eats beef, it’s tragic. Bengali hindus have eaten beef at Nizam’s or Olypub for decades, why all of a sudden people are making a scene out of it! Who gives anyone the right to tell you what to eat? When such non-issues are made into issues, you know there’s a specific agenda behind it. Resist that. I personally find it extremely fascinating to experience the different types of food while traveling. One should be open to experimenting with local and indigenous foods. You don’t go to Goa to eat biryani!

Nietzsche said, “Live dangerously.” Anjan Niye seems to echo that idea. As you looked back on your life while writing your memoir at 73, what did that experience feel like?

Anjan: Like I said, my life is a circus. A fun one. And I’m the trapeze artist swinging from one end to the other. A reckless youth, breaking my father's dream of me being a barrister, choosing theatre over a stable job, moving from theatre to cinema, winning an international award at a young age but still failing to succeed as an actor, then suddenly getting famous as a singer at 43—it’s all part of that grand circus. I've always done what I wanted. Not all of it was good, but I have had fun. I never cared about pleasing the market, never worried if I’d have money in the bank or buy a car next year. Badal Babu once asked me if I could be alone. He said, "To be an artist, you must learn to be alone. You will love, marry, have kids, but at the end of the day, you must be alone." Because of this madness for my work, I couldn't have been a very responsible husband or father. My wife, Chanda, has somehow accepted this lunacy. For 46 years, we have been loving, fighting, knowing, demanding, forgiving, pushing each other for elbow room, risking, damaging, trying to undo the damage, unlearning, learning yet never ever trying to play safe. We grew older together. We grew up to be together.

Whether I’m a bad person or just a wrong person, time will tell. For now, my son Neel is still my best friend; he still plays guitar with me.

Writing this memoir was hard because I’ve forgotten things, and the people I could ask are gone. There’s so much left unsaid. I promise to cover those people and stories in the second part.

Like most your songs, and films 'Anjan Niye' ends with a note of triumph rather than despair. Are you still an optimist?

Anjan: I made films like Bow Barracks Forever or Finally Bhalobasha because this city still gives me that space. No matter how much it declines, Kolkata doesn't teach you to lose. Yes, much has changed. But the circus remains. People still flock to bookshops, Swiggy and uber hasn't totally swallowed the city yet, they still crowd into old buses, still stand in line at Nahoum’s for cakes baked by Muslim hands, celebrate Eid, still take to the streets to protest when it matters–That's my pride. That is what will keep Kolkata alive.