Summary of this article

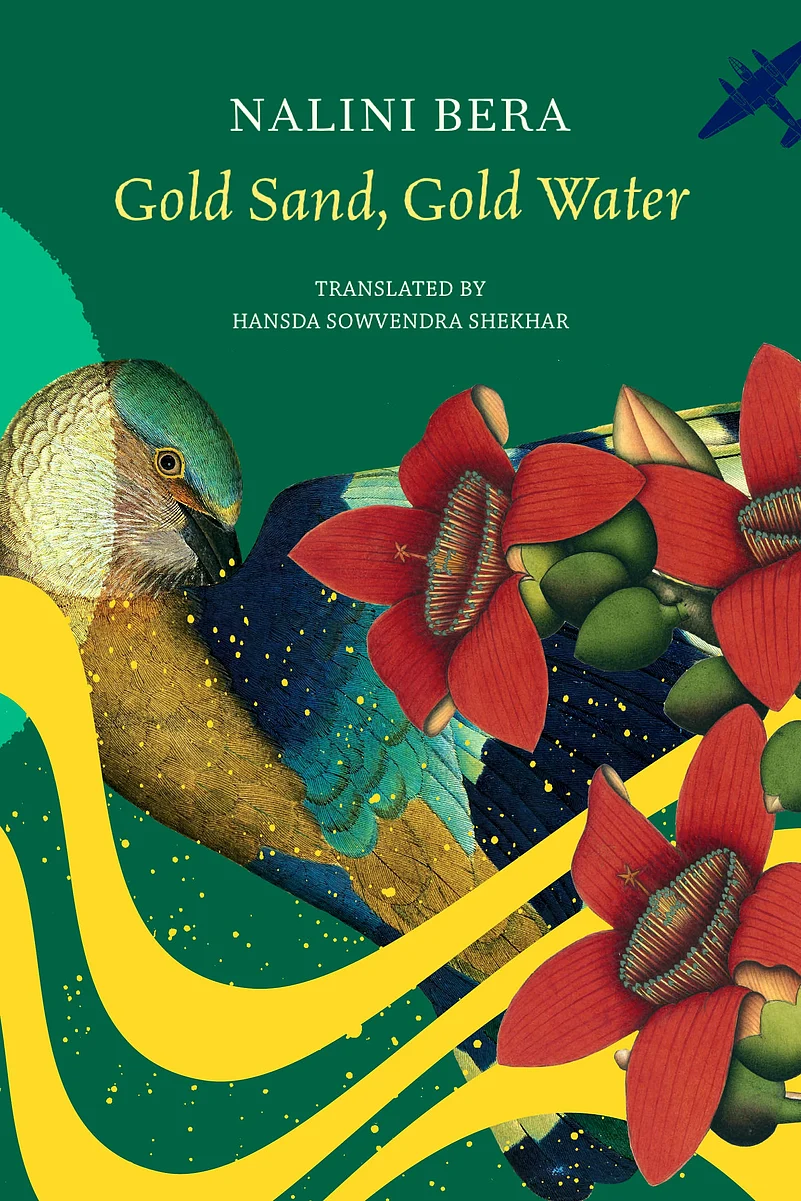

In Gold Sand, Gold Water, Nalini Bera brings together folklore with realism.

Bera's novel is a panoramic view into a disappearing way of life.

Published by Seagull Books, Gold Sand, Gold Water is a translation of Subarnarenu Subarnarekha for which Bera was awarded the Ananda Puraskar in 2019.

The farthest I could go to from my house was to the villages of Rohini and Ranjitpur. The river Subarnarekha lay to the north of our village. Beyond the river was a small hillock that we called hoodi. The whole of our village could be seen from the top of that hillock. And the river and the sands of the river. There were the villages of Kusturiya, Hatibandhi, Labkishorpur and Andhari on the banks of a tributary we called the Dulung river. Crossing it, there was a small stream named Gorkata. On the other side of the Gorkata stream was the village Rohini, and just after Rohini was the village Ranjitpur.

My landmark used to be a dead simul tree near the Gorkata stream. That dead simul tree was home to crows and egrets. And in case the Bautia Bhoot—the ghost that haunts the village roads—accosted one or if one forgot the route, then that dead simul tree was the only landmark. Every day, so many of us from my village crossed two rivers to get to the Choudhurani Rukmini Debi High School in Rohini village where I studied. The village of Rohini had a mansion that belonged to a landlord. That mansion was called Babu Ghar.

We took one of two routes to get to our school: through the Babu Ghar in Rohini; or by the side of the Nilkuthi—another mansion—in Kusturiya village, keeping the Babu Ghar to our right. Under the scorching sun during the summers, a snake lay in the shade of the broken bricks in the Nilkuthi, smelling the air with its tongue, lost in thought; a kingfisher pointed its beak towards a pool of water while perched on the branch of a dumur tree growing out of the broken walls of the Nilkuthi; and, away from the snake and the kingfisher, a white dove cooed—its throat expanding as it did so—from the parapet.

The river Subarnarekha. When I looked from the top of the hillock, everything beyond the Subarnarekha was my own country—the swades; while everything on this side of the Subarnarekha was foreign to me—the bides. Bides, as in Bilet—that is, England—and America. Everyone on this side of the river Subarnarekha was to me the Nodipaarer Lok—the People on the Other Side of the River. And those People on the Other Side of the River were as foreign to me as a person from England or America would be. And that was obvious. For, on this side of the river were the landlord’s mansion, the palace of Rani Shailabala, the huge building of the high school and the rice mills owned by the Khatua people. The Khatua people were Hatua people only; they too spoke a mix of Bengali and Odia. But just because they owned shops and rice mills and other businesses, they were relatively more prosperous than the Hatua people. Hence, they, considered themselves higher in status. Dimauli, Salua, Khadgapur and Medinipur were on this side of the river. Howrah and Kolkata were on this side of the river. So many factories and machines were on this side of the river.

And what was on our side of the river? There were plants, like mutha gholghosi saranti, susni, ghorakana, nahanga, bonpui, bon kalla, chyanka and shak palha. There were vegetables and food plants, like kankro, kundri, bhela, bhudru, kend, kosha phol, aanwala, paan aaloo, khaam aaloo, chun, churka, meha, and madal. There were sports, like ha-du-du, danriya, kati, ekom-dukom and football which we played with a ball made of ol—elephant-foot yam—stems we tied and bundled together. There were nights of spotting constellations, like dodhi, bhariya, saat bhaya, kaalpurusha, bhulka, bhurkha and rabonraja. There were ghosts, like raat bhit chidkin, gomuha, kala muhi, kuchla, saat bhouni, jhaapdi and bautia. There was equipment, like pata, ghuni, gaanti, mathaphabdi and the chargodiya net to catch fish.

There was Hanshi Nauria who helped us cross the river. There was Pramath Paramanik, of the barber caste, who cut our hair. When Mejo Kaka took me for a haircut, he told Paramanik, ‘O Pramath, Nalin’s hair has grown like a horse’s tail. Cut it short.’ Pramath said, ‘Not today, uncle. Some other day.’ We returned on ‘some other day’, and Pramath said the same, ‘Not today, some other day.’ Pramath Paramanik’s negligence made my hair grow like the creepers of gourd and pumpkin. If he showed mercy on me some day and actually got down to cut my hair, he shaved off a good part of my scalp. He completely tonsured me on the day of Srimanta-da’s wedding. I felt so bad I cannot say how much.

The Subarnarekha in my country is purbagamini—that is, it takes a turn and flows towards the east—purba. Standing on the Simultola ghat by the Subarnarekha in our village, one can see the river for a long distance. The Dulung river flows by the Choudhurani Rukminidevi High School in Rohini, by the villages of Kusturiya and Hatibandhi and into the Subarnarekha near the villages of Nabakishorpur and Andhari. The big river and the small river, together their expanse looks akin to that of a sea. The villages of Kusturiya, Andhari, Hatibandhi and Laudaha might be the usual villages, with their dirt and lack of resources, but, for us, Those Villages on the Other Side of the River were London, Nottinghamshire, Canada and California. Bilet and America.

When Hanshi Nauria, whose height must have been only four feet, splashed in the rain-filled waters of the Subarnarekha in the months of Srabon and Bhadra—July-August—wearing his striped lungi, and rowed us across from the ghat at Kusturiya to the ghat at Barodanga, it seemed as if Vasco da Gama had pulled into the port at Calicut. I told Hanshi what I thought, that I saw him as some Vasco da Gama. But he laughed it all away. ‘Thao,’ he said. Thao, in Hanshi’s dialect, meant ‘let it be’. But was it so easy to let it be? After all, wasn’t it Hanshi Nauria himself who took me on my adventures in the waters of the Subarnarekha? Hanshi took me to see the Jahajkanar Jongol—the Forest of Crying Ships—in the middle of the Subarnarekha. It was said that several ships carrying wealth and spices capsized at that particular spot in the Subarnarekha, crying as they went down. It meant that, perhaps, sometime in the past, there was enough water and enough strong waves and enough powerful tides in the Subarnarekha to drown full-sized ships. And, after all, the Bay of Bengal wasn’t too far away. It was said that the crying of those capsized ships could be heard even today. It was said that the People on That Side of the River had actually seen those ships and heard them cry. There were also so many trees in the Forest of Crying Ships, perhaps that is why it was called a forest. Those trees were all unknown to us. They were not our usual sal, mahul, aasan, kuchla and koim trees. They were not even the spice trees of cinnamon and clove—and to think that those capsized ships were carrying spices! Who knows what kind of spices those ships were carrying? Who knows what other seeds or plants those ships were carrying that led to the growth of such strange trees in the Forest of Crying Ships? Hanshi Nauria pushed his boat against a tree and asked me, ‘Lolin, which tree is this, can you tell me?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, my good boatman. That is what I have to find out. But this is why I call you Vasco da Gama, because you lead me to such discoveries.’

During the rains, when the river Subarnarekha and all the streams were filled to the brim; when the water from the river and the streams reached up to the limits of the villages of Andhari, Nabakishorpur, Borodanga and Khuriya; when the villages of Karantala and Pakurtala were submerged in the flood waters; when the villages of Khandarpara and Deulbar were almost under water; when fish and turtles swam alongside the legs of our cattle as they walked in the fields and materialized in the grounds of our village school, Hanshi Nauria came to my house and called out, ‘Lolin, will you come on a boat trip with me?’ Hanshi Nauria called our boat trips ‘nouka bilas’—nouka, boat; bilas, pleasure. Our boat trips used to be pleasure trips. For the nouka bilas, the boat was decorated with flowers, sandalwood paste, mustard oil and vermilion—and Hanshi Nauria was always enthusiastic for such a show. For his boat was the only boat chosen for nouka bilas, his boat was the only boat kept ready for such shows. There were passengers too, to go on such nouka bilas: the kirtan team of our village, who sang the devotional songs in praise of Lord Krishna. They had tilak on their foreheads and necklaces made of wooden beads around their necks. They wore vests as white as gourd flowers on their torsos, tied a dhoti around their waists, and threw a gamchha around their shoulders. Merrily, they played on their khol, kartal and gupiyantra, and their nouka bilas began. But it was more than just a pleasure trip on a boat; it was a gathering of people who talked about everything under the sun and entertained as well as enlightened themselves. The boat would shuffle through the night, merriment on board, and reach the other bank only at daybreak. By the time they reached the other bank, the sun could be seen rising from the bosom of the Subarnarekha. The Lodha people from the forests also crossed the river early in the morning to sell the wood they had gathered, but they were not concerned with when the sun rose and in which ditch it rolled into, for they simply did not have that much time. Their main concern was their work and survival. When the mist precipitated over spider webs on brinjal plants and the Lodha people finally had the leisure to look at the sun, they’d think that the sun had, like an unruly calf, jumped out of somewhere into the sky. Every morning, a play of colours happened on the waters of the Subarnarekha. Who knows, the sun itself might have spread all those colours on the water, from where tiny waves picked them up and started their own play! Hanshi Nauria too played in his own way with those colours. In the midst of the colours of the sun and the water, the blue of Hanshi’s lungi looked like the body of a peacock.

So, when we all went for our pleasure boat trip, the kirtan team and boys of my age, and left behind all the villages, I often felt that the currents in the river would take us somewhere far away, where I, like Amerigo Vespucci and Marco Polo, would discover a new land, something like Gulliver’s Land of the Lilliputs, and someone would whisper in my ear, ‘Traveller, have you lost your path?’ In reality, nothing such happened. Neither a typhoon carried us anywhere, nor did we fall into the water.

Hanshi Nauria was a capable boatman. At the end of the pleasure trip, he dropped us safely at our homes. There went my dreams of becoming another Vespucci or Polo or da Gama or even a Gulliver! Yet, I returned to the river, again and again. I sat on its grassy shore, played with the grass and flowers on the river’s bank and looked at the people by the riverside. So many people crossed over from this bank to that, so many came from that bank to this. Many of them travelled along the course of the river, east to west, and west to east. I often felt like following those who went westwards. They would reach their destinations, the villages they were headed to. But my journey wouldn’t end with theirs. I would just go on, and on, and on . . .

Nalini Bera is a Bengali novelist and short-story writer, centres marginalised rural communities in his fiction. He received the Bankim Puraskar (2008) and the Ananda Puraskar (2019) for Subarnarenu Subarnarekha.

Excerpted with permission from Seagull Books