Summary of this article

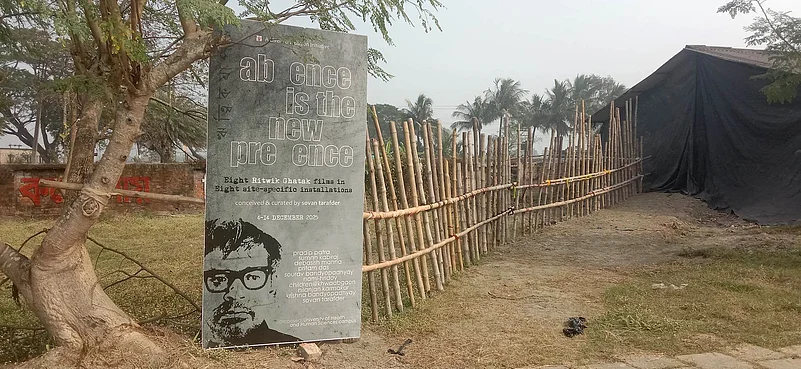

The site-specific installation exhibition titled Absence Is The New Presence in Kolkata is curated by author and filmmaker Sovan Tarafdar.

It offers a rare, stylised approach to remembering a filmmaker from the past, where the act of paying tribute became an artistic gesture in its own right.

In the exhibtion, eight contemporary artists respond to Ghatak's eight films, while remaining attentive to questions of space, time and context.

As 2026 progresses, film lovers find themselves looking back at a year dense with personal and collective reckonings—from the 50 years of Sholay (1975) and the birth centenaries of Peter Sellers, Guru Dutt, Paul Newman and Ritwik Ghatak, to the losses that marked the period, from Robert Redford and Gene Hackman to our own Dharmendra. While celebrations and commemorations assume many forms, a site-specific installation exhibition titled Absence Is The New Presence stood apart from conventional tributes. Conceived as a centenary response to Ghatak, the exhibition, curated by author and filmmaker Sovan Tarafdar, engages with the filmmaker’s eight feature films through dialogues with eight contemporary artists—each responding to a single work—while remaining acutely attentive to questions of space, time and context.

As a Bengali film student and practitioner, I often question Ghatak’s relevance in an era of accelerated audiovisual consumption, where 30-second social media reels shape our attention spans and eight-hour OTT series have become a familiar staple. Yet, since the beginning of last year, frequent references in the media to Ghatak’s influence on acclaimed contemporary filmmakers—from Subhash Ghai and Adoor Gopalakrishnan to Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Anup Singh—suggested that his cinematic ethos continues to exert a lasting impact. While Bengali film clubs, film studies departments, festivals and film schools across the country marked Ghatak’s birth centenary, the exhibition Absence Is The New Presence moves decisively beyond ordinary commemoration. Radical in both intent and form, it offers a rare, stylised approach to remembering a filmmaker from the past, where the act of paying tribute became an artistic gesture in its own right—distinctive and almost unprecedented in the Indian context.

When asked about the significance of the title, Tarafdar—the curator and principal ideator of the exhibition—explained that Absence Is the New Presence arises from both etymological and conceptual inquiry. The word absence derives from the prefix ab, commonly understood as “not there” or “away from.” Less often noted, however, is that ab also signifies a point of origin. Embedded within the term, therefore, is a productive paradox: absence does not merely denote loss, but also the possibility of beginning.

To recall Ghatak today is to confront his absence. Though no longer physically present, his cinema continues to inhabit our cultural and political consciousness. The task, then, is not to mourn what is missing, but to activate it—to transform absence into a present mode of engagement. Reading Ghatak from the vantage point of our own time allows new meanings to surface as his films encounter contemporary realities.

Accordingly, the exhibition does not seek to replicate, recreate, or conventionally commemorate Ghatak. Instead, it proposes a process of negotiation: what happens when Subarnarekha (1965), Nagarik (1977), or Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973) are placed in dialogue with the urgencies of the present? How do these works resonate within today’s socio-political and ecological contexts?

In engaging with these questions, the exhibition approaches Ghatak’s cinema through translation, carrying affect, memory, and political urgency into contemporary art installations, rather than relying on direct representation. Each work responds to a specific film, allowing the artists to inhabit Ghatak’s concerns while firmly situating them in the present moment.

Nagarik, as KYC (Know Your Citizen), designed by artist Pradip Patra, is revisited in the context of contemporary debates on citizenship, particularly during the period of the SIR exercise. Eight decades after Partition, the figure of the refugee resurfaces—this time rendered faceless, visible only through disembodied legs. Accompanied by a short video installation by Subhajit Naskar, the work reflects on how the idea of citizenship has mutated into a dystopian condition today. For Tarafdar, engaging with this unsettling continuity became a way of paying tribute to Nagarik.

Ajantrik (1958), as First Name Car-Man, created by artist Debasish Manna, explores the unusual bond between a man and his car—between the human and the mechanical. Revisiting this relationship through the lens of absurdity allows the machine to assume human qualities, while the human appears increasingly mechanised. In the age of artificial intelligence, Ajantrik feels strikingly anachronistic. The installation embraced this anachronism—entirely analogue and devoid of techno-aesthetic cues, the vintage object is transformed into a human-like figure, asserting its temporal dissonance as a conscious artistic choice.

Bari Theke Paliye (1958), as in Home and the World, interrogates the urban, middle-class gaze that often frames exhibitions. Children from Khwaabgaon, Jharkhand, mentored by Mrinal Mandal, were invited to express their responses to the film through paintings. The intention here was to rupture that dominant perspective by allowing non-urban and non-adult interpretations to intervene—to hold a mirror up to the urban imagination and disrupt its assumed authority.

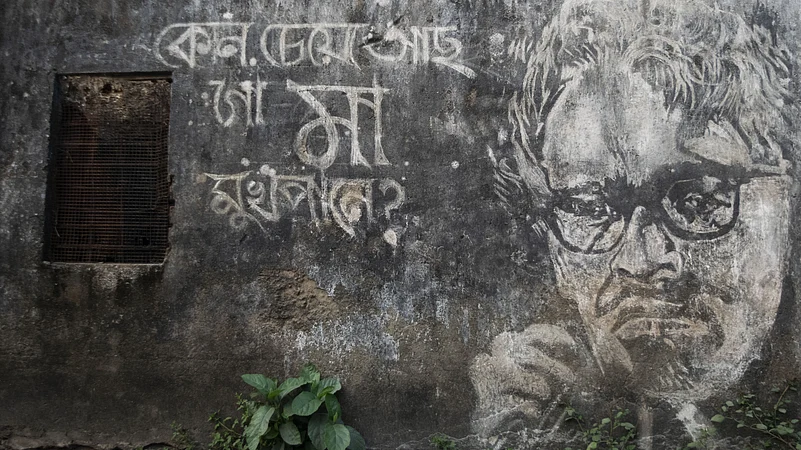

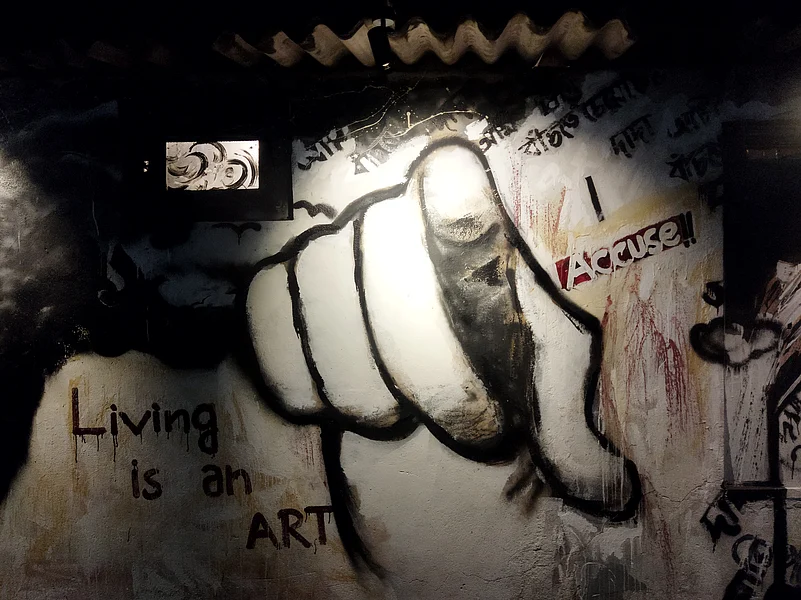

Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), as In/Ex(Cluded) by Krishna Banerjee and NaMi-Ridoy takes the form of wall graffiti. Two opposing walls face each other—one bearing the familiar image of Neeta, the other intervened upon. In this reimagining, Neeta raises her finger in accusation, echoing the declaration “I accuse.” Through graffiti—an art form historically rooted in rebellion—the installation envisioned Neeta’s liberation, transforming the wall into a site of resistance.

Komal Gandhar (1961), as in The Partition Sonata by Sourav Bandyopadhyay, centres on the overlapping cartographies of land and mind. What happens when these two maps intersect? This question guides the intervention, where maps are imposed onto the faces of Anasuya and Bhrigu, echoing a similar gesture applied to photographs of Ghatak and Surama’s (Ritwik Ghatak’s wife Surama Ghatak) wedding. Consciously avoiding a sombre or fatalistic reading, while remaining aware that the division of land inevitably fractures the psyche, the work aligns with Ghatak’s refusal to dwell solely in despair. Instead, it gestures toward the present: Komal Gandhar emerges as an impossible dream, yet one that compels us to continue dreaming. A subtle subtext also acknowledged the centenary of the Communist Party of India, recalling Ghatak’s resistance to ideological enclosures imposed by the party.

Subarnarekha as Past.Indefinite, by Nilanjan Karmakar and Sovan Tarafdar, unfolds through multiple spatial explorations in a photo-documentary mode. The first examines Cooper’s Camp in Ranaghat—arguably the oldest refugee camp in the subcontinent—focusing on a house where women like Bagdi Bou were once confined. The second recreates Kali, the terrible mother, with Dhaneshwar Bairagyo as Kali and Oishini Dey as the child, staged in Orgram near Gushkara—an abandoned British airstrip whose runway remains eerily intact. The third reflects on the river Subarnarekha itself, observing how little has changed in the lives around it, apart from the intrusion of mobile phones. A fourth intervention presents a hanging door marked with a patch of red—an eternal site of interrogation. It recalls the moment when Ishwar pushes open the door to discover Sita standing on the other side, posing the unresolved question: to open the door, or to turn away?

In Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, as in The River Remembers by Suman Kabiraj, boats appear suspended—not floating in water, but in the air. The river no longer exists as a physical entity; it survives as memory, as absence. Titas becomes a metaphor for loss, for something that once was and is no more. The installation space dissolves into amorphous forms, invoking climate change and the cyclical repetition of history. The work stands as a testament to the river.

Finally, Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974) as Reason, Debate and a Contour, by artist Pritam Das, is reimagined in the form of a graphic novel, casting Nilkantha Bagchi as a postmodern superhero. His primary weapon is not physical strength but analytical thought. Volatile, self-destructive, and dangerously incisive, he raises a troubling question: is contemporary society equipped to confront a figure whose power lies in relentless reasoning?

The exhibition, which began on December 4, 2025, is being held at an abandoned cattle-breeding facility in Sonarpur, about an hour’s drive from Kolkata. The Liver Foundation, Indian Institute of Liver and Digestive Sciences has provided the space. The exhibition, sponsored by the Foundation, will run for 100 days to mark Ghatak’s centenary. This abandoned site, possibly no longer vacant in the near future, on the fringes of Kolkata’s bustling urban life resonates, almost uncannily, with Ghatak’s lifelong engagement with the refugee crisis and the Partition of Bengal, as well as his own marginal position within mainstream cinema and lived experience.

Debarati Gupta is a Filmmaker, Columnist & Guest Lecturer at Calcutta University