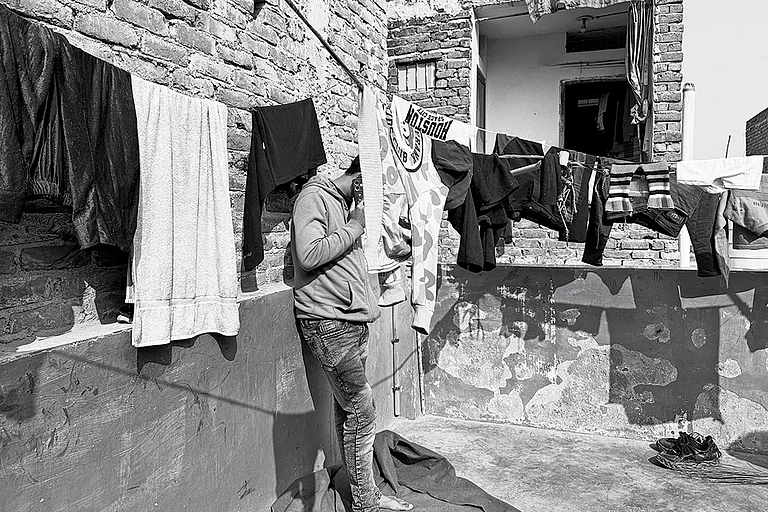

Survivors of the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in Delhi’s Tilak Vihar recall decades of loss and survival.

Women narrate stories of violence, resilience and rebuilding life in the widows’ colony.

Justice for the 1984 massacre remains incomplete as key trials continue four decades later.

In the autumn of 1984, Delhi’s streets burned with a fury that left an indelible scar on India’s conscience. Following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards on October 31 that year, organised pogroms targeting Sikhs swept through the capital and beyond. Over 2,700 Sikhs were killed in Delhi, leaving over 1300 widows and 4000 orphaned. Homes were looted, gurdwaras set ablaze, and families torn apart in a wave of violence that survivors describe as a betrayal of the state itself. Forty years later, the wounds remain raw for survivors.

As The Tree Fell

“I did not know who Indira Gandhi was, I rarely ever left my house to know what even Trilokpuri looked like,” recalls Harleen Kaur (name changed), now in her late-fifties, seated on the cot in a flat the government bequeathed her 38 years ago. She still fondly remembers her jhuggi that burned down in Trilokpuri of East Delhi in 1984.

Harleen Kaur, 17 and newly married, lived in Trilokpuri, one of the first sites to be hit by the waves of mobs that dispersed across Delhi. She describes him as a tall built man who abhorred violence. He left with his truck at four in the morning on November first, but came back early with a foreboding message, “they’re killing all the Sardars.”

“He asked me to make tea, and left the house to buy vegetables. I made rotis, rotis he never got to eat,” says Kaur. Her husband rushed back, gripped her arm, and entrusted her to his sister: “Didi, ye meri amanat hai, isko bachake rakhna (Protect her, sister, for she is my valuable possession).” Those were his last words. For three days, Kaur knew nothing of his fate. Then her mother-in-law recounted seeing him hacked in half by a mob, his body smeared across the road; she gathered his remains in her lap and wailed all night. Desperate for safety, Kaur and her sister-in-law hid as another relative was dragged away.

“As the morning dawned, they were already killing us, butchering our bodies, burning us alive,” says Lakshmi Kaur, who was 29 at the time of the attacks. “I felt blind, not knowing where to go. I roamed with no one to even give us water, bleeding and shivering. We had children in our hands, screaming out of hunger, thirst. How can a child live like that for three nights?”

Lakshmi Kaur and her niece Pappi Kaur arrived together at the widow colony. At 15, Pappi witnessed ten family members murdered in the violence. “Mobsters with daggers and chemicals—some from our own colony—burned our gurudwara, then stormed the gullies to burn us alive,” she recalls. “We stepped over bodies. Some were killers, some looters, and some rapists, but none were saviours.”

Women and girls were grouped together, and dragged out to the streets, and cases of public gang rapes have been reported en masse, as more and more sexual assault victims of 1984 come forward with their story. By the time the army and police forces descended upon many affected areas on November 3, there were no Sikhs left to salvage anymore.

As Indira Gandhi's lifeless body was set to flame at Rajghat on November 3, hundreds of Sikhs were suffering from the same fate on the other side of the river. “People call it ‘riots.’ It was not a riot. Ye sarkari qatl-e-aam tha. (state sponsored mass murder)” adds Pappi Kaur. A month later, then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi proclaimed to a crowd on the occasion of his mother's birthday, “When a giant tree falls, the Earth shakes.” The Earth shook for over seventy-two hours before the bereaved had to embark on a migration to what we now know as Tilak Vihar, a one-of-a-kind widow colony.

Halfway Home

Until the morning of November 1, 1984, Block 32 of Trilokpuri (East Delhi) was home for 15-year-old Pappi Kaur and her family—a place of routine, of neighbours who knew each other by name. But that name became the very reason they were marked. "They had come with the intent to destroy both us and our homes," Kaur recalls.

“I lost my husband but I am thankful that at least my honour was saved,” says Harleen Kaur. However she recalls how women were not spared, even in the relief camps. “They were handing out rotis on one hand and eyeing the women on the other,” Kaur says. “They were watching closely, looking out for someone young, someone they found beautiful, someone they could take. In fact, they did take two young women.”

Laxmi Kaur was a Sevak at the Sultanpuri Gurudwara where she once lived. She may be confined to her bed, but not to silence. In her lap rests a book on the 1984 carnage — a reminder she holds close, not just of what was done to them, but of why remembering still matters.

“They then gathered us on buses and took us to a gurdwara, where they set up camps for us,” Kaur recounts. “Some would give us clothes, some would give milk or ration, and some would set up langars for us.”

Pappi Kaur, recalling her time in the Shahdara relief camp, remembers how families were handed huge cooking vessels "just like the ones used in jails.” They cooked together, using whatever they had, and then shared the food among all other families in the camp.

“On our way to the camp, one woman gave birth. I had a chaddar—I tore it up and wrapped the baby girl in it,” says Kaur. “I even cut the umbilical cord myself, with a knife. I’ve seen so many such births during those days.”

After spending a few months in the relief camps, the survivors were eventually moved to a newly built colony in Tilak Vihar and rows of flats meant for rehabilitation. "Chits were there," she says. "I picked one and got this flat." Although people living in those flats figured out that each flat was a mirror image of the other. One kitchen, one bathroom, a single room, and a bulb.

Every year in November, Pappi Kaur along with other survivors go to Trilokpuri. Buses full of people come together for Paath Sahib in the Trilokpuri Gurdwara, which was burnt down in 1984 but is now rebuilt. There are structures that are new in appearance, but they are not theirs. All they see is ruins.

Of Rage & Remembrance

As soon as you enter her room, on the fourth floor of the dilapidated building, the one thing that will hook your attention in Harleen Kaur’s home immediately is this painting titled A Marriage Ceremony that demonstrates a quintessential wedding scene in a Sikh family. A bride sits in the center being adorned by the women in her life: sisters, a grandmother, a young girl watching in awe.

This is not Kaur, nor her daughter. Kaur never had a daughter, a fact she remorsefully ponders over, looking at the painting. The painting is merely representational, bought off for 150 rupees by Kaur in 2015.

In her very neat drawing room, life and death are tightly held together, lest the wounds of 1984 rip open without invitation. In this neat drawing room, the shelf showcases a frame with young Kaur alongside her granddaughter Noor, the daughter she never had.

For people like Kaur, the struggle did not end with 1984, it continued to debilitate the psyche for the generations of her family to come. Now the only semblance of hope for Kaur is ensuring a good education for her grandchildren.

“When someone asks questions, I respond and cry, my heart feels lighter. If not for this, I would feel stifled bearing all of this inside me. Those same visuals, everything keeps surfacing in my head,” Kaur says.

Laxmi Kaur takes turns between offering solace and receiving it from other women. “We meet at the Gurudwara and tell each other, ‘Behenji, I am retired now, Behenji, I need to get my daughter married.”

Talking is also a desperate attempt at remembrance, it's a struggle against the erasure of history. “Some people prefer not to talk about it but I can not restrain myself,” Pappi Kaur adds. The process does not seem to be ending anytime soon. It’s a process of women sitting together, grieving together, women talking, women in rage, and women refusing to forgive and forget.

In Search Of A Better Life

Families in Tilak Vihar continue to live in crumbling homes that were allotted to them after the violence. The flats in Tilak Vihar are visibly deteriorating—walls are cracked, and ceilings leak, making them a dangerous place to live in. Residents allege that there is no help from the government for the electricity. The Aam Aadmi Party government installed electric meters soon after coming to power in 2015 and since then the residents do not pay the bills. They demand that the government should subsidise the electricity for all.

Amar Singh, a resident of B-block, said that he was unable to maintain his house and sustain his family for months, until he got the promised government job in June this year, after decades of wait. His mother was pregnant with him when the violence occurred. He lost his father and uncles in the carnage. He said that his mother struggled to bring him up since childhood, as she did not get any government job after the violence.

In addition to the poor housing, Tilak Vihar is grappling with severe sanitation issues. A large garbage dump has formed right behind a government school in the area, and locals say it has become a permanent fixture. The area lacks community parks for children. A park in block B has garbage dumped right around the corner.

Devender Singh, a 22-year-old resident, said, “Sewage drains were constructed just before the elections. After the results were declared, the drains have not been cleaned, and the roads have not been maintained.”

“We don’t need sympathy,” said one resident, “We need action on the front of jobs, sanitation, the homes we live in.”

The neighbourhood Gurdwara Shaheed Ganj Sahib helps each other with repairs, looks after elders who live alone, and supports school-going children. NGOs occasionally run health camps and distribute essentials, but sustained government support, they say, is what’s urgently needed.

Against All Odds

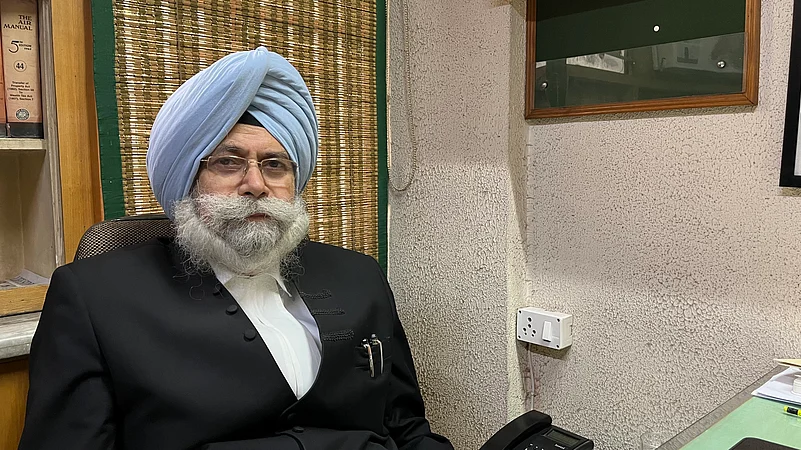

The Nanavati Commission (2000–2004) found Congress leaders Jagdish Tytler and Sajjan Kumar “very probably” incited the violence. Senior advocate H S Phoolka, representing victims pro bono for over 30 years, states: “The 1984 riots were not spontaneous—they were a planned massacre enabled by those in power, with police as accomplices.”

Lakhwinder Kaur, now 58, lost husband Badal Singh when a mob stormed Gurdwara Pul Bangash, stabbing him with his own kirpan and burning him alive—one of three killed. Surender Singh, a granthi survivor, told her the details.

Resettled in Tilak Vihar, her whereabouts were unknown when CBI tried closing Tytler’s case in 2007. Another survivor, Nirpreet Kaur, found her and urged her to fight. “Lakhwinder showed immense courage under huge pressure,” says advocate Phoolka. Her 2007 protest petition was pivotal in keeping Tytler’s case alive.”

Between 2008–2015, CBI filed two additional closure reports, both rejected by Delhi courts for poor investigations. Lakhwinder’s 2024 testimony at Rouse Avenue Court was a turning point: she relayed eyewitness Surender Singh’s account of Tytler inciting the mob. This strengthened charges of murder, rioting, and abetment against Tytler. As of now, the trial continues, with further hearings scheduled.

Nirpreet Kaur was 16 when she watched her father—gurdwara president Nirmal Singh—burned alive by a mob. “I saw him in flames, helpless,” she said. Her testimony secured Sajjan Kumar’s 2018 life sentence for five Raj Nagar murders. In February 2025, he received another life term for the Saraswati Vihar killings. A third case against him is in its final argument stage.

Arijit Gupta, Harishankar Manoj, Isha Kazmi, Sumit Singh & Tuiyba Anwar are freelance journalists based in Delhi.