Summary of this article

Recollection of a blind Adivasi man who shared a silent, ritualised bond with the author’s family through weekly Sunday meals in 1950s Jamshedpur.

The man’s sudden disappearance leaves a deeper imprint than his presence, especially on the author’s mother, revealing how small acts of kindness create enduring human connections.

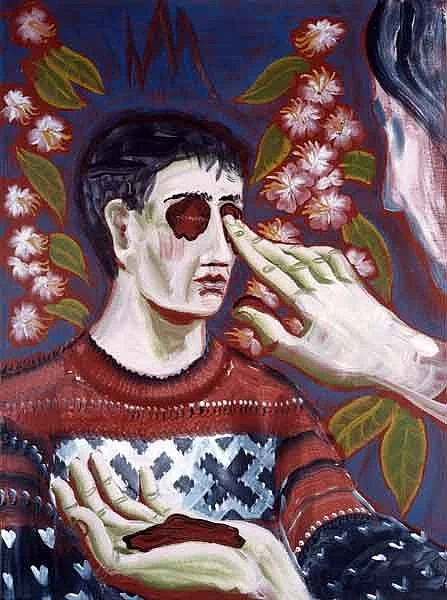

Reflections link personal memory with literature and cinema, Colley Cibber’s poem The Blind Boy and Buñuel’s Los Olvidados, to contrast different representations of blindness, suffering, and dignity

When we were growing up in Jamshedpur in the ‘fifties, for some years, every Sunday afternoon, a blind man of Adivasi stock given to finding his way with the help of a stout lathi, used to come tap-tapping to our backdoor. He would announce his arrival with two loud words, Maa eseychhi (Mother, I have come), to which she would respond, Bhalo, boso (Good, be seated). He would enter by the backdoor, now unlatched by one of us, and sit on the ground, the uthon or backyard.

The blind man was tall and dark, stoutly-built, and dressed in a banyan with holes in it, khaki shorts and a pair of heavy workman’s boots which seemed to have been discarded by its original owner after years of rough use. He looked unbelievably majestic.

His eyes were big and appeared to be protruding out of their sockets; the white had turned a bit yellow. Out of a jhola would materialise an aged enamel thali and a tumbler for holding drinking water, battered and equally worn-out. These he would carefully place on the ground – and wait. My little sister and I, five years her senior, would position ourselves a short distance away from our visitor, our curiosity knowing no bounds. In our minds, we must have asked ourselves a hundred questions about the man. Even though the weekly ritual continued for long, our curiosity never waned.

Sunday being Sunday, the lunch we had on the opening day of the week would be a bit out of the ordinary; mind you, just a bit, because those were years of daily struggle for our hard-pressed parents. There were many mouths to feed, including some not born of them, and the usual middle-class obligations to be met. But we knew that somewhere even in this none-too-bright scenario, there was a little space for the blind man.

On his thali, there would be bhaat, dal, torkari, sometimes a bhaja of some kind or the other, and a piece of fish. But it was understood that mother could afford to dish out second helpings of only the first three items. All this must have happened more than sixty years ago, yet I still remember the satisfaction on the man’s face as he ate the simple fare.

Lunch over, he would drain down his throat a substantial amount of water. Before taking leave of us, he would light a biri, pull on it a few times, letting the smoke out of his nostrils. He would then put out the biri and place it back in his jhola. His departing words would invariably be, Maa, bhalo khelam (Mother, I ate well), to which Mother would say, Abaar esho (Come again). He would tap-tap out of the uthon as he had tap-tapped in.

Then, it so happened, one Sunday our visitor failed to turn up. We waited for him till around two when, usually, he would be at our door by one at the latest, but there was no sign of him. Everyone in the family, but most of all Mother, grew anxious. Had he fallen sick, we wondered, or, god forbid, something more serious had happened. We had our meal, but spent the rest of the day in a state of unease. Very soon, another Sunday was upon us and the collective wait for the blind man began again. But he failed to turn up once again, much to the renewed disappointment of every member of the family.

After that, several Sundays came and went, but there was no sign of him, and gradually we came to accept that we would not see our man again. After a few months, we ceased to miss the tap-tapping or the jets of biri smoke escaping through the man’s enormous nostrils. Occasionally, one or the other of us would say something about him, but it was only in passing. My sister and I grew older and got on to other things, but Mother who had nowhere to go, confined as she was to her puja room and her ranna ghar (kitchen), seemed to be the last in the family to give up on our Sunday guest.

Many years later when I first saw Bunuel’s Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned), a dark cruel journey through violence and betrayal, for the first time in a film society screening in Calcutta, I was reminded of the blind man who had once been a part of our Sunday routine in Kadma (a kind of hard white Bengali sweet), which is what our part of Jamshedpur was called.

But where Bunuel’s blind man was a horror to view, and would retaliate with great violence when attacked by a group of young malcontents, ours was a peaceful person, benign and even philosophical in the way he conducted himself. Two more dissimilar men deprived of the blessing of sight would be difficult to imagine. Two contrasting images cling to my mind – one is of the lost Latin aimlessly lunging at his youthful persecutors with all the viciousness he could muster; and the other who would announce his arrival briefly with the words, Maa eseychhi, and felt no need to say anything more till he had partaken of Mother’s generosity.

Talking of people who cannot see, when I was in Standard 2, my classmates and I had to memorise a poem called The Blind Boy by the British poet Colley Cibber. Mrs Muriel Kirwan, a grey-haired, rare Anglo-Indian lady, was our class teacher with a special interest in elocution. Each of us had to recite the poem in front of the whole class and if we faltered, we would be gently ticked off and told to do better. The soft firmness, bordering on maternal concern, with which she handled us made her a popular figure. She made us learn the poem by heart with such serious intent that, to this day, I can recall the agony of the blind boy and his brave effort to console himself: Oh say what is that thing call’d light, which I must ne’er enjoy; what are the blessings of the sight, Oh tell your poor blind boy!

Sometimes I ask myself whether it is possible that our friend of the Sunday lunch, ever thought of the same things as his much younger counterpart did in a poem written in a faraway land.

(Vidyarthy Chatterjee lived practically his whole life in Jamshedpur. Currently, he resides in Kolkata.)