Summary of this article

Bengali cinema grew out of literature, folk traditions and a strong socialist ethos, centering its stories on the working classes.

The 50s and 60s birthed a new wave which nurtured a screen shared by literature and the socio-economic realities of rural and the urban.

Bengali cinema gradually shifted from the streets to domestic chambers, exploring personal aspirations, centrist comforts, and anxieties.

There is something about Bengalis, cinema and winter. Across Kolkata, conversations about the state of Bengali cinema blend with cultural laments—formal and informal—as the soft winter sun settles over the city. Kolkata tries hard to outgrow its clichés, but they would stall that comfortably until summer.

Amid all this, you often hear gentle eulogies for a bygone era and for the political core Bengal has long shed.

“Where did it all go?” is a familiar Bong lament. But do we really want the answer?

After Independence, Bengali cinema grew out of literature, folk traditions and a strong socialist ethos, centering its stories on the working classes as they navigated identity, exploitation, belonging and displacement. Over the years, though, it has undergone a sweeping churn—of ideology, cinematic language and allegiance.

The relationship between leftist politics in Bengal and its cinema was layered and uneasy, mirroring the left’s own history in the state. From the beginning, at the heart of its cinematic art lay a socialist core unafraid to confront the issues of the day. With the wounds of famine and partition still fresh—and with rising prices, unemployment and widening social divides—these realities were too stark for most artists to ignore in favour of commercial fiction.

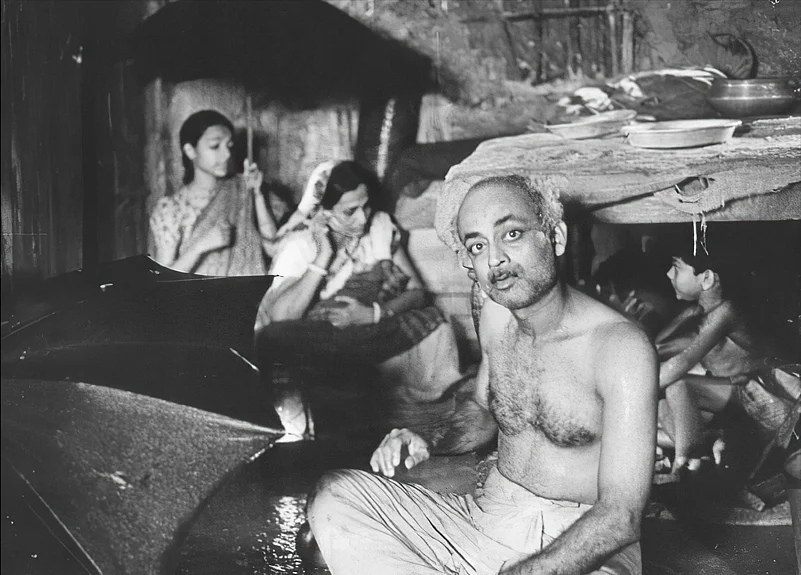

Going back to Chinnamul (1950), the first Indian film to address partition, Bengali cinema focussed on the displaced, the oppressed and the working class even before the New Wave of Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak emerged.

The socialist seeds were sown in the years of Nehruvian policy, industrial awakening and anti-imperialist, anti-feudal movements, and the ‘leftist concern’ in Bengali cinema underwent major shifts in the decades that followed.

The Wave and The Rage

Marked by political upheaval and a churn in sensibilities with a neo-realism setting in, the 50s and 60s birthed a new wave which nurtured a screen shared by literature and the socio-economic realities of rural and the urban.

Often, it was artistry and transgression overlapped in art. With Ray’s debut film Pather Panchali (1955) financed by the Congress government in the state, it was understood that the cultural ambience sought to value the artistic voice. However, in 1959, Mrinal Sen’s Neel Akasher Niche, a film obliquely engaging a political conversation, also became the first film to be banned in India.

For Ray, the first decade of his filmmaking shows a synthesis of the personal and political, with a deliberate focus on ideology, lyrical expression and cultural identity. In contrast, Sen and Ghatak mostly employed a more direct, raw cinematic style, foregrounding grassroot trauma, angst, and distrust of authority

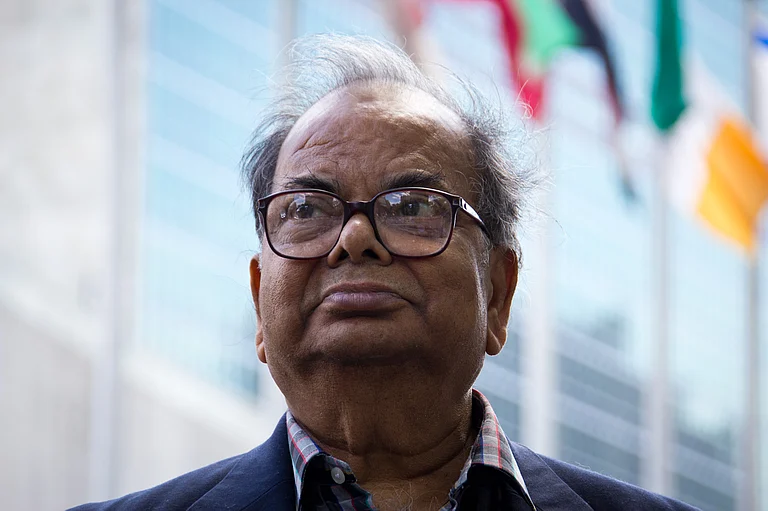

Film theorist Sayandeb Chowdhury traces this political intensity to a deep-rooted scepticism toward the state and elite power. “Congress’ origins in the elite and upper castes, in Bengal and across India, meant that artists inherited a general distrust of authority. Even with Nehru’s socialist inclinations, the artistic stance remained wary of the state.”

Despite this scepticism, Ray, Sen, and Ghatak often engaged directly with Nehru and Indira Gandhi, negotiating spaces of artistic recognition, if not outright endorsement.

“Given the colonial state’s behaviour and a lack of accountability, there was an ingrained dissatisfaction with an idea of the state which was more general and not directed at individuals. This could be attributed to a broader socialist framework, or a postcolonial distrust towards the popular domain which consistently left out the common man,” adds Chowdhury.

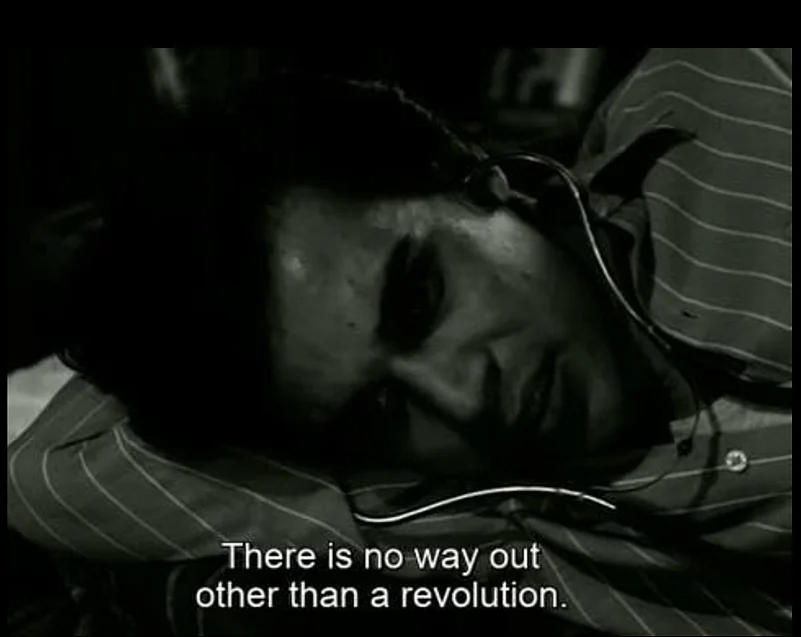

Through the 60s and 70s, amidst violent political flux in Bengal and the country, the angst on screen only grew in temper further highlighting the disillusionment and distrust of the masses.

Nationally, land reform movements, rise of labour unions, the Naxalbari uprising, the Emergency and even international political shifts triggered by the Cold War and the Vietnam War cast a distinguishable impact on cinema emerging out of Bengal.

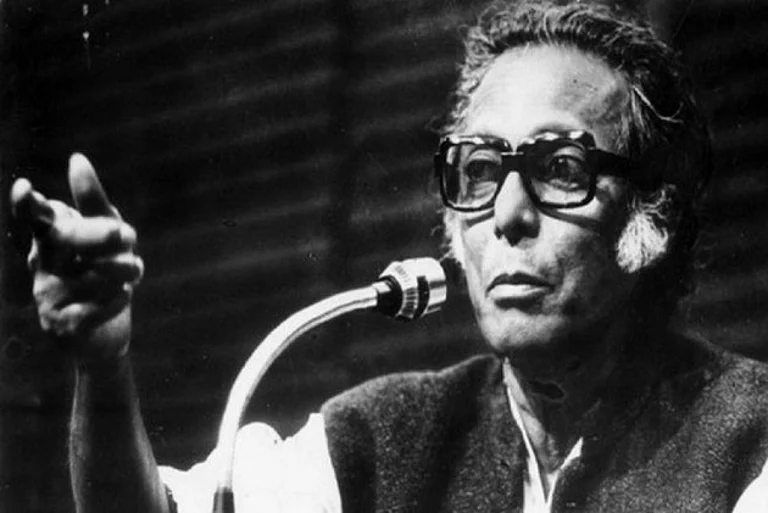

Mrinal Sen had famously said, “since poverty, famine and social injustice are dominant facts of my own times, my business as a filmmaker is to understand them.”

Among others, Ghatak’s Partition Trilogy (Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar, Subarnarekha) and the Calcutta Trilogies by Ray (Pratidwandi, Seemabaddha and Jana Aranya) and Sen (Interview, Calcutta 71 and Padatik) defined the cinematic core shaped by ideas and insecurities of the working class while bringing them to the centre.

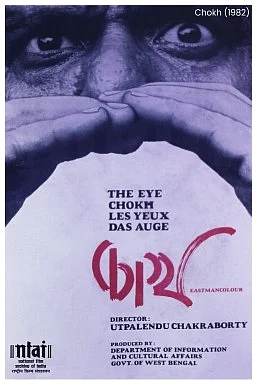

Even into the 80s, with the Left Front in power in the state, relatively fresh names like Goutam Ghose, Utpalendu Chakrabarty, Buddhadeb Dasgupta also contributed to the palette of ‘political films’ in addition to that of the triumvirate. Bengal, by then boasted, of a rich tradition of political filmmaking not only engaging leftist thought but harnessing them against the establishment.

Into The Centre and the Chamber

With economic liberalisation and satellite television entering middle-class homes, Bengali cinema gradually shifted from the streets to domestic chambers, exploring personal aspirations, centrist comforts, and anxieties.

Chowdhury highlights the changing middle-class attitude towards the state. “As prosperity grew and the pain of hunger and partition receded in Bengal, trust in the state increased,” he says, linking this to cinema’s changing focus.

He adds that the shift went beyond economics, noting the caution artists exercised to avoid alienating the middle class: “The state went from being ‘guilty until proven innocent’ to ‘innocent until proven guilty’. In that sense, the CPI(M)’s greatest success was convincing the cultural and academic elite they no longer needed to act as custodians of these concerns after coming to power.”

In the 1990s, the National Film Development Corporation’s (NFDC) restructuring and withdrawal from supporting art cinema left politically charged films without funding, paving the way for a more homogenous, narrative-driven, depoliticised arthouse cinema.

Director Anik Dutta, a critical supporter of the Left, observes: “We never had leftist propaganda cinema, but leftist sensibility was omnipresent in the Bengali middle-class psyche. There was disillusionment in the 80s and 90s, but society remained largely left of centre.” He recalls Ray noting that while he was not formally aligned with the Left, those around him invariably were.

For Dutta, the 2011 fall of the Left crystallised the shift in art and cinema. “It’s a chicken-and-egg situation: did the shift cause the fall of the Left, or vice versa? Either way, fear or favour drove the change. Proximity to power became profitable.”

Even a decade into the century, fading embers of political cinema remained, but critics argue that changing ideology and governance further moved the narrative away from the ‘personal is political’ ethos of filmmakers like Aparna Sen, Rituparno Ghosh, and a gentler Goutam Ghose, towards depoliticisation and anti-intellectualism.

“You don’t need a political film to convey a political atmosphere, but erudite isolation mattered. What happened outside didn’t enter the screen,” says Dutta, director of Bhooter Bhabishyat (2012), one of the few recent Bengali socio-political satires.

He also notes that politics in Bengal increasingly became religiously polarised, further sidelining the Left. “There is so much happening—corruption, crises—but none reaches cinema. People fear going against the wave and breaking the status quo,” he adds.

Speaking of the softening stance even within prominent names of the 80s and 90s, Dutta believes, “voices earlier prominent took a step back to invest into the new dispensation, with more to gain out of it. It was a slight trade-off.”

Despite milking nostalgia out of the bygone through constant hat-tips, rehashes and revisits, the screen in Bengal is mostly a stranger to the realities and rage of the day, blind to the flux- almost repulsed by it.

Personal endorsement of leftist thought among artistes has been pushed to the edge with a complete collapse of the firewall between the government and the community. However, like Chowdhury and Dutta observe, the hobnobbing and panegyrics remain consistent to meet mutually profitable targets, and that - probably defines the responsibility of the artist in today’s Bengal.

Once the cauldron of rooted political conversations on screen, Bengali cinema looks away, in complacency and comfort - unbothered, moisturised, in its own lane.