Summary of this article

No Other Choice premiered at the Venice Film Festival, vying for the Golden Lion.

It circles a job candidate hastening to eliminate all competition.

The film is poised to be a major Oscar contender.

In Park Chan-wook’s No Other Choice, capitalism rears itself as a vicious, persistent ghost. Present-day disaffections, crossing between livelihood and identity, roll over characters, dilemmas and unrelenting fears of losing everything. When the film opens, Man-soo (Lee Byung-hun) gets fancy fish gifted by his workplace. He naively sees it as token of appreciation for his diligent service. The truth is more distressing. He’s among the many who’ve been laid off with American buyers swooping in on the paper firm.

A stray comment from his wife, Yoo Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), triggers his grand scheme. What if a lightning bolt fells a rival candidate? What if the other applicants, for the same job Man-soo is seeking, happen to die one by one? It’s a delicious proposition, yet something about it doesn’t wholly take off. You can sense the string work behind the chaos too much. Surrendering to the ride becomes inversely proportional to its own diabolical inventiveness. The premise’s bloodthirsty potential is betrayed by diminishing returns as body count accrues. No Other Choice gradually genuflects into becoming overly pat in the eliminations.

The track with the first victim and his wife is the strongest and most cohesive. There’s detailing of characters, their knit desires, drudgery and lies nurtured over years widening the cut. Park’s gift for sexual intrigue and heat dominates here, Yeom hye-ran upping the ante and dialing high the provocation. A snake bite scene, laced with a mistaken reveal, is a masterclass in erotic suspense. Lust and abasement combine in Park’s archetypal fugue-like ways. It leads up to a confrontation for the ages, scored with Park's mischief.

Adapted from Donald Westlake’s 1997 novel The Ax, the film loops apprehensions undergirding the first victim’s situation to Man-soo’s own. He grows to imbibe the same anxieties and insecurities—his masculinity threatened by his wife’s work-sphere relationships. Could she too, like the victim’s wife, be cheating on the sly? These tensions upholster the film only up to a certain point. But it risks being mangled by a sketchy sub-plot with Man-soo’s son and his own misdeeds. There’s a tender moment the father and son share, spun into the inherent loneliness of doing something terrible.

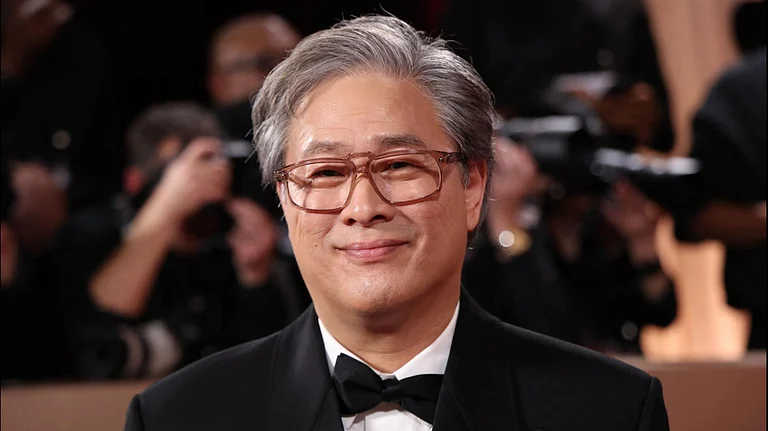

Park is among contemporary cinema’s sleekest stylists. Be it the vengeance trilogy or The Handmaiden (2016), the director can unleash the chaos of survival and manipulation into a thrilling vortex. Sculpted methods vibrate with the elemental madness of human nature, often tucked away. In Park’s hands, nothing is politely contained. You anxiously wait for detonations. The early sections in No Other Choice have the twang of things going south. Park maps the drama onto two couples, each mirroring the other’s worst impulses, accelerating the freefall. Man-soo projects the envy of his prey, the bitter defeat of losing love to the younger.

However, No Other Choice is ridden with too many rough edges. It sits in an unwieldy place between Park’s breathtaking stylization and narrative disjunctions. This is a thriller alerting you to its slants and skewed angles. Park is known to wickedly delight in the oddest angles and ingenious, spectacular dissolves. Pleasures are designed to be found in its showy mayhem—the careening slip of morality when capitalism really leaves you with no other choice. Park’s stylistic choices meshed seamlessly with utter mysteries of the human heart in his previous outing, Decision To Leave (2022). That film’s several layers of ambiguous selves found a perfect fit in Tang Wei, who sneaked through technical artifice. In No Other Choice, visual and editing choices jar against plot orchestrations. These exert as rude distractions, instead of melding into narrative fabric. As Park tosses you deeper into the hole where morality chokes and is drowned out altogether, it all becomes increasingly drearily vapid. The less you speak about actual police work, the better. Cards seem to magically fall into place for Man-soo’s road to open up.

In an age where job precarity and disposability are as steep as ever, No Other Choice can hit abrasively. Park rounds up the glib HR machinery, erratic layoffs that can knock down even seasoned employees. No one is safe from the axe. Man-soo realizes being canny is his only life-raft. Cut-throat survival need not mind bulldozing through human concessions. The film’s key problem is that its atmospheric, thematic anxieties constantly upstage the individual. The best Park films leave you breathless in a weave of hypnotic violence and scalding emotion. No Other Choice struggles to locate Man-soo and Mi-ri. The family’s survival never quite carries the immediacy Man-soo launches in panic. Swindling by enterprises leaks into one’s own self. The moral corrosion rusts upon the soul so inexorably there’s no turning back. By the end, Man-soo’s triumph takes a backseat to the question if he can at all confront the weight of his deeds. Even if he does get the coveted spot, would he be able to live with his sins?

No Other Choice harvests existential paranoia from this question, right up to its soul-numbed close. Holding this dislocated self, Byung-hun can be sincere, crafty, awkward and funny—all within a beat. There couldn’t have been a more fitting reservoir of the film’s absurd swings. Stepping in as the other undiluted moral half that also corrupts, Mi-ri lends wrenching depth to Park’s manic mess. She’s the embattled heart of this film whilst Byung-hun’s Man-soo grazes competition with industrial efficiency. No Other Choice should have bent further into their wrangle. It’s a pity that energy is so misspent on other diversions.