Summary of this article

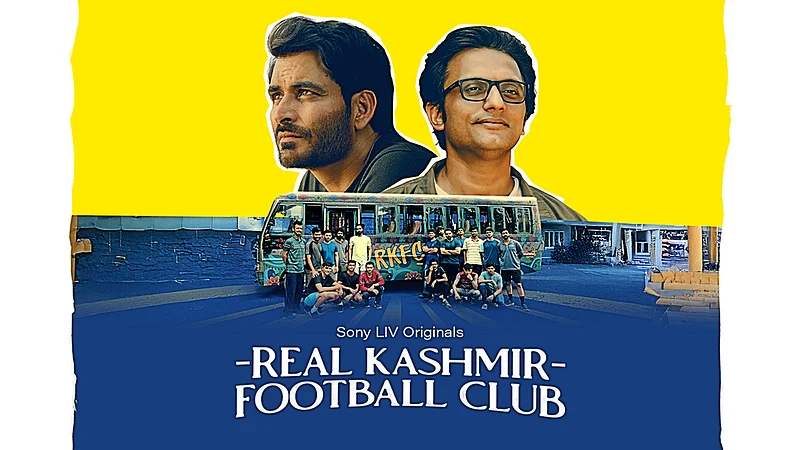

Real Kashmir Football Club is a Sony Liv Originals series which released on December 9.

The story is based on the inception of a football club by a disillusioned journalist and a liquor business owner in Kashmir.

In hesitating to venture into the political realm, the screenplay struggles to endow some characters with a complete sense of personhood.

The origin story of Real Kashmir Football Club (RKFC) begins with the floods that devastated the valley in 2014. In the wake of widespread destruction and loss of lives, Sohail (Mohd. Zeeshaan Ayyub) finds his journalism job disappointing and sensationalist. He believes Kashmir’s youth need hope and a firm purpose to keep them from wasting their energy, potential, and talent. Historically, football has been a popular sport in the region and it becomes the means through which Sohail, a resourceful, jugaadu and persuasive person, begins to realise his dream of establishing a football club in Kashmir.

In the quest to secure funding, he meets Shishir (Manav Kaul), who runs a liquor business in Srinagar amidst regular ire from those who deem it haram (sin). Based on actual events, these two become the founders of RKFC. This eight-episode series straddles supposedly incompatible thoughts—Kashmir as part of India and Kashmir as a land belonging to its own people—with an understated poise. Through sport, the identity of a state and its people is affirmed without provoking bureaucratic and governmental unrest. By alluding to different states with their own football clubs, the series hints towards federalism and momentarily seizes it.

Furthermore, in the simplicity and innocuousness of sport, a football team forms to heal a community of Kashmiris, from elderly widows and young impressionable boys to Pandits. The unsettling aspect—although not surprising, given the widespread and absurd censorship of art depicting Muslims as central protagonists—stems from the series (co-directed by Rajesh Mapuskar and Mahesh Mathai) failing to explore how the widows lost their husbands and why the Kashmiri youth constantly suspect their identities are at the risk of being erased.

Even when a film is set in the past, whether recent past like in this series or further back in history, omitting how the present (such as the aftermath of the repeal of Article 370 or the reorganisation of J&K into Union territories or terror attacks) informs and reshapes our understanding of previous years creates a vacuum. The spectator is left feeling there is nothing truly egregious in a zone of conflict. This tames the potential of a series like this. Nevertheless, when the fragmented and oblique references to militarisation, protests, unemployment, mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits, and general unrest in the region dissolve, they also present a world where Kashmiris are humanised, in a country that has normalised their exclusion, alienation and hatred towards them over the past decade.

Some characters are well-developed, such as Sohail, Shishir, Rudra, and Amaan, while others, like Mustafa (coach) and Azlan (star player) as well as their rivalry lack clear motivation. Abhishant Rana, who plays Amaan, shines in his portrayal of a character undergoing a change of heart, subtly capturing the complexities of an aimless, yet honourable young boy. Perhaps, in hesitating to venture into the political realm, the screenplay struggles to endow some characters with a complete sense of personhood. If intention and effort were the only criteria, then Real Kashmir Football Club would be rated very highly.

Episodes 7 and 8, titled “Counterattack” and “Goal,” are arguably the best of the eight, sustaining a pace synchronous with the rhythm of football, as RKFC prepares to play against the 27 rifles. An international coach from Scotland arrives to witness large parts of the valley cordoned off, the wedding of Dilshad’s sister is arranged in their junkyard-cum-practice-ground, a win seems to be around the corner after a series of losses, players unite forgoing differences and the fear of moving in and out of a cantonment area is temporarily suspended by a flurry of excited spectators lining up to root for their football club. The payoff is good for both on-screen and off-screen viewers. One leaves feeling triumphant and somewhat uncaged.

Srishti Walia is a doctoral student of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.