Summary of this article

India AI Impact Summit 2026 highlights AI’s potential but raises alarms over data centres’ heavy water use in a water-stressed nation.

Experts warn data centre water consumption could more than double to 358 billion litres by 2030, intensifying scarcity risks.

Summit discusses solutions like efficient cooling and renewables while announcing major AI infrastructure investments.

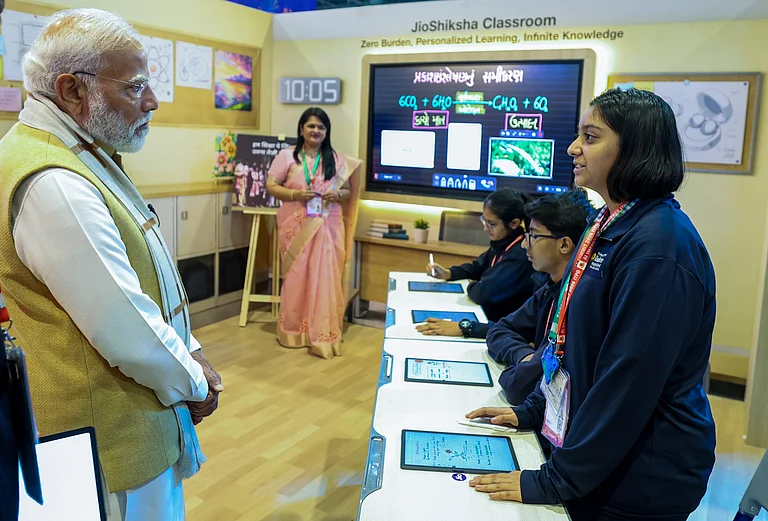

The India AI Impact Summit 2026 is taking place at Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi. The event has brought together more than 20 heads of state, 60 ministers, 500 global AI leaders, and people from over 100 countries. The goal is to promote responsible artificial intelligence that helps the Global South.

The programme includes high-level talks, an AI expo with 300 exhibitors, innovation challenges, and sessions about how AI can help in healthcare, agriculture, education, manufacturing, and climate resilience.

The summit is built around three main ideas: "People, Planet, and Progress". It wants to move the global conversation about AI from general ideas to real actions, such as making computing power available to more people and supporting fair growth for everyone.

The emphasis is on creation of more AI infrastructure, including many new data centres. Announcements during the event point to partnerships and investments worth up to $200 billion for data centres in the next few years. This has drawn attention to a serious environmental problem: India is already short of water, and data centres use a lot of it.

On February 17, speaking at a press conference, Union Minister for Electronics and Information Technology Ashwini Vaishnaw said the "requirement of power and water is a major concern" for AI infrastructure. At the same time, he explained that the government is offering long-term tax holidays to attract investments in data centres and to encourage more sustainable ways of building them.

India has 18% of the world’s population but only 4% of its freshwater. The World Bank calls India one of the most water-stressed countries. Its reports warn that, without big changes, many parts of India could face severe water scarcity by 2040 because of growing demand, poor management, and climate change.

Recent studies warn that pushing AI growth so hard could make India’s water problems worse.

A BBC report from 2025, titled "Google, Meta, Amazon: India's data centre boom confronts a water challenge", includes an S&P Global study from the same year. It predicts that 60–80% of India’s data centres will face high water stress this decade. Most of these centres are built in cities such as Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru — places where water is already in short supply and shared between homes, industries, and other users.

The same BBC article says India’s data centres are expected to use more than double the water — from 150 billion litres in 2025 to 358 billion litres by 2030. This could drain underground water sources and rivers even more.

A 2025 report by Planet Tracker, a London-based non-profit that studies sustainable finance, says many of India’s nearly 250 existing data centres are in very water-scarce areas. As AI grows, this will increase competition for water and make local communities more worried about fair access.

Morgan Stanley’s report from September 2025 predicts that global data centre water use will rise 11 times to 1,068 billion litres a year by 2028. AI is the main reason. More than half of the biggest data centres are in places with medium to high water stress. These patterns are especially worrying for fast-growing countries like India.

The main problem is cooling. AI tasks create huge amounts of heat inside servers. Most data centres in India use evaporative cooling because temperatures are high. This method uses water to take away the heat, but a large amount of that water simply evaporates and is lost.

A Bloomberg article 2025, called "AI Is Draining Water From Areas That Need It Most", explains that data centres usually evaporate about 80% of the water they take. Only the rest goes to wastewater treatment. This waste is worst in places already short of water. Even though 163 million Indians do not have reliable clean water (according to NITI Aayog’s 2019 report), data centres often use clean drinking water to protect their equipment from damage.

The summit has faced these issues head-on.

On 16 February, a session called "Harnessing AI for Water Resilience and Sustainable Growth" looked at how AI can help solve water shortages — for example, by predicting leaks, checking for pollution, and sharing water more fairly. At the same time, the panelists admitted that data centres themselves use a lot of water and energy.

Arunabha Ghosh is CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). He also chairs the summit’s AI and Climate Expert Engagement Group. On 17 February, during a discussion on AI and climate, Ghosh said data centres are significantly contingent on power demand, on water demand and cooling demand. You need to then develop this infrastructure that is ready for the future, not just leveraging the present."

Ghosh described AI’s "duality", it can help create clean energy and make systems more resilient, but the huge data centres it needs are "incredibly thirsty for power and water for cooling". He said we must carefully measure and reduce the energy and water used so AI supports climate goals instead of harming them.

The same message came up again in a special session called "From Insights to Action for Resilient, High-Performance Data Centres". This was run together with the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Lab of the Rockies. A Press Information Bureau release that same day said the session described data centres as "power and even water guzzlers" with large carbon footprints. It talked about the connection between energy and water, better cooling methods, choosing locations with less water stress, and the need for better planning to fix scattered rules.

Even the official IndiaAI portal notes that global data centres could use nearly 3% of the world’s electricity by 2030. AI is pushing power use per server rack above 100 kW, and whole facilities need hundreds of megawatts — all of which increases water demand in India.

There are also hidden effects: AI needs so much electricity that it pulls power from plants (often coal or nuclear in India) that use large amounts of water to cool their turbines. Sometimes this off-site water use is even bigger than what the data centre itself uses. The International Energy Agency’s 2025 projections — mentioned in summit materials — say global water use linked to AI could reach 4.2–6.6 billion cubic metres a year by 2027.

Even with these risks, the summit is giving a lot of attention to solutions.

The Resilience, Innovation & Efficiency Working Group has discussed new ideas like closed-loop cooling systems. These could cut freshwater use by 70% or more. Other options include using treated wastewater, building centres powered by renewables, and placing them in areas with less water stress.

A report by Observer Research Foundation recommends mandatory checks of environmental impact, rewards for greener computing, and using AI to improve water security — for example, predicting floods or managing irrigation better.

NITI Aayog keeps reminding everyone in its water reports that millions of people still do not have reliable clean water. It stresses that we need strong rules so AI progress does not make inequality worse.

Specific investment signals at the summit underscore the stakes. On 17 February, Google CEO Sundar Pichai announced a partnership with Reliance Jio for new cloud clusters and a 50 MW renewable energy project in Rajasthan to power AI data centres, while NVIDIA partnered with Yotta for sovereign AI infrastructure using over 20,000 Blackwell Ultra GPUs. Larsen & Toubro also proposed a venture under the India AI Mission for GW-scale NVIDIA AI factories. These align with the government's plan to deploy 38,000 GPUs for national shared infrastructure, as discussed in bilateral meetings.

As the summit concludes, it represents a pivotal test for India's AI vision. Balancing innovation with sustainability requires translating these discussions into enforceable measures: stricter siting regulations, efficiency mandates, and transparency on resource consumption.

Without them, the digital leap celebrated here could parch communities and undermine the inclusive, planet-conscious future the event envisions.