Summary of this article

Digital infrastructure without physical and social access worsens exclusion

The panel highlighted how supposedly neutral AI reproduces existing inequalities

Panellists called for stronger community-led data governance and continuous feedback

Imagine trekking 5 kilometers through rural India, paying Rs 100 for authentication in an alien language, just to claim rice and lentils. AI now only extracts your data instead of helping you. This isn't dystopia; it's the reality for millions as digital public infrastructure (DPI) races ahead, powered by black-box AI that risks mass exclusion. At Impact AI, a powerhouse panel demanded ethical AI that serves people, not exploits them, urging India to bridge hype and humanity before it's too late.

The session, Data, People, and Pre-Empting Mass Exclusion: Building Ethical AI as Digital Public Infrastructure, brought together Arpita Kanjilal of the Digital Empowerment Foundation, Dr Bhavani Rao R from UNESCO W4EAISAC, Nicolas Miailhe from AI Safety Connect, Osama Manzar of the Digital Empowerment Foundation, Paola Galvez Callirgos from Globethics, and Ram Papatla, APAC Trust and Safety lead at Google.

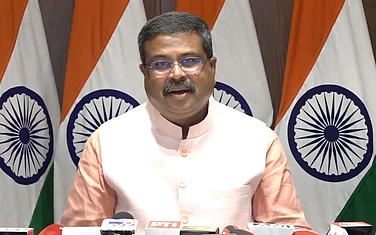

Osama Manzar, Digital Empowerment Foundation co-founder, stripped away corporate and government fanfare. Rural India lacks roads or water, yet digital claims to be the new infrastructure. “The tech or the pipeline has to be available so that this data can go,” he said, but it's 5 km away, costly, and linguistically inaccessible. AI must simplify, not complicate: "Data of the people or data for the people?" DPI needs to be doorstep-affordable, in consumable formats. With 65 per cent unconnected, tech serves itself first, unless the script is flipped.

Nicolas Miailhe of AI Safety Connect painted a chilling picture: We're building civilisation on opaque machine-learning black boxes, opaque even to designers. The algorithmic society empowers elites while fringes get steamrolled. "We have to be at the table or on the menu," he warned. In India's service economy, exclusion is a catch-22, AI is arriving regardless of readiness, and opting out is rarely an option.

Paola Galvez Callirgos grounded the discussion in lived harm. She cited the case of a Peruvian farmworker whose worn fingerprints led an algorithm to deny her a food subsidy, and the Dutch welfare scandal where migrant families were falsely flagged as fraud risks due to biased datasets. Ethical charters and AI laws exist, she noted, but they often lack enforcement, creating a vast “implementation gap”. Power asymmetries allow external actors to extract and hoard data, as seen in initiatives such as Latin America’s “LatamGPT”. The solution, she argued, lies in operationalising ethics with communities themselves. “We need to enter the digital era with our values intact.”

Dr Bhavani Rao R drove home a fundamental truth: no system can ever claim neutrality. She pointed to well-documented examples where medical research and pharmaceutical datasets are overwhelmingly based on male bodies, embedding gender bias directly into algorithms—even in countries with advanced data ecosystems. In contexts like India, where comprehensive datasets barely exist, the risks are magnified. Biases are human, she said; technology merely amplifies the prejudices we carry into it.

This raises a critical question: who owns the data—and therefore who has the power to manipulate it? For most people, especially those in informal sectors, their lives are shaped daily by the biases of others, while their own realities never make it into the data at all. Data sovereignty, she stressed, is essential. What matters to one community may not matter to another, yet entire populations remain statistically invisible. If their data is never reflected in the system, how do we even begin to talk about utility?

From the industry side, Ram Papatla emphasised the need for stronger feedback loops between developers, policymakers, and the communities affected by AI systems. Without continuous, meaningful feedback, even identifying the right problems becomes difficult. Building digital systems, he argued, must go hand in hand with building bridges—spaces for rich, insightful conversations that connect technical design with lived experience.

The panel delivered a stark message: ethical AI cannot be an afterthought layered onto digital public infrastructure. Without accessibility, data sovereignty, accountability, and genuine community participation, DPI risks becoming another mechanism of exclusion.