Summary of this article

The imprisonment of individuals for exercising those rights should deeply trouble its democratic conscience.

When power runs out of answers to questions of governance, it turns to repression, and imprisonment becomes a central tool of control.

For those who return from prison, the challenge is not only political but also deeply personal.

The demand for the release of political prisoners today is haunted by a dangerous vagueness. As the category expands, its meaning becomes thinner. While there is broad agreement that a political prisoner is someone incarcerated for political beliefs or political acts, this definition is deeply inadequate. At best, it allows us to see only the tip of the iceberg.

Such a definition privileges ideologically articulated political action, conscious dissent, and, crucially, the privilege of choosing whether one wants to act politically and risk imprisonment. It excludes vast numbers of people whose lives

are shaped by state violence, but whose resistance does not arrive wrapped in political vocabulary. Adivasis asserting their right over jal, jangal, and zameen are criminalised. Dalits demanding protection from caste atrocities and asking for the bare minimum of dignity are jailed. Muslims are imprisoned in an atmosphere thick with lynchings and pogroms. Palestinians are incarcerated under a genocidal occupation. To insist that political imprisonment requires an expressed political consciousness is to reduce state violence to ideological dissent alone and to deny the deeply political nature of mass incarceration.

This narrowing becomes even more troubling when courts uncritically reproduce prosecution narratives, as seen in recent cases such as those of Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid. Thousands of lesser known, unnamed, and unprivileged people remain imprisoned under trivial, fabricated, or botched up charges. In such a situation, the demand for release cannot remain confined to legal arguments alone. It inevitably spills into the social realm and must take the form of a political movement.

Yet there is remarkably little organised effort to secure the release of political prisoners. Whatever exists has steadily retreated from sustained collective organising to the fragile and easily targeted space of social media. This shift appears logical only because the state has relentlessly criminalised even the mildest attempts to raise the issue of political imprisonment. The most chilling example remains the case of Delhi University professor G. N. Saibaba. After his arrest, a defence committee was formed to campaign for his release. At least five of its members were later arrested in the Bhima Koregaon Elgar Parishad case.

When I met Hany Babu after his release last month, he told me that during his interrogation he was repeatedly questioned not about the violence of 2018, but about Saibaba. This revealed the state’s deep anxiety about any collective voice that demands the release of political prisoners. I am aware of students who were picked up by the police merely for planning, not even organising, a solidarity meeting for Umar Khalid and others. Suspicion shadows every attempt at solidarity.

My own house was raided by the National Investigation Agency (NIA) for my work on the release of political prisoners. Police harassment has been relentless. This reflects what my co-accused Ehtesham Siddique once described as the state’s deep insecurity. The objective is not investigation alone. It is to silence dissent and prevent any sustained questioning of the inhumane machinery of oppression unleashed against those who defend the oppressed. Instead of responding with repression, the state should be compelled to address the issues being raised and ensure that justice is pursued rather than systematically denied.

The demand for the release of political prisoners is necessary because any democracy claims pride in guaranteeing fundamental rights. The imprisonment of individuals for exercising those rights should deeply trouble its democratic conscience. Such incarceration is never confined to the individual alone. It sends a calculated message to everyone else. Whether it is an activist like Umar Khalid or Sudha Bharadwaj, a scholar like Sharjeel Imam or Anand Teltumbde, or a lawyer like Surendra Gadling in the Bhima Koregaon case, the warning is unmistakable. Fall in line or face the same fate.

This message is directed as much at ordinary citizens as it is at dissenters. For any democracy that claims to be rooted at the grassroots to survive, state repression cannot be treated as an isolated legal issue to be fought only in courtrooms. The causes of political prisoners must be taken up collectively by citizen groups, conscious individuals, and even mainstream political parties. When power runs out of answers to questions of governance, it turns to repression, and imprisonment becomes a central tool of control.

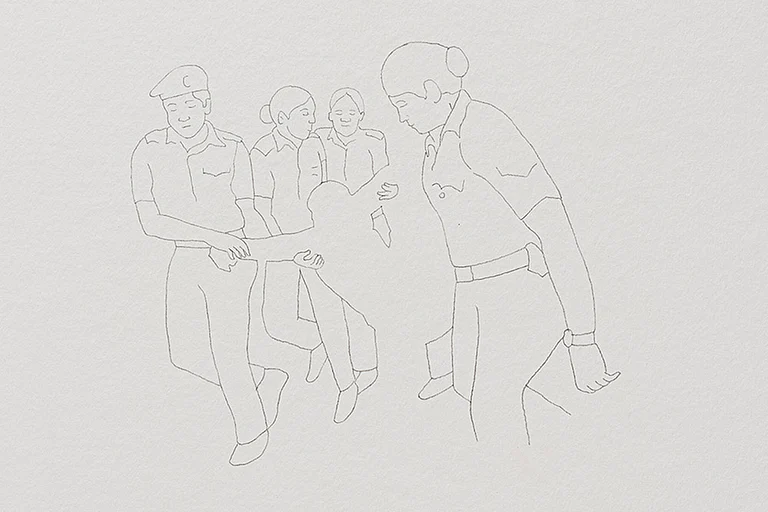

By 2023, this pattern had become familiar to me. From time to time, large-scale raids were carried out in Padgha, Thane, with 15 or 20 houses searched at once. These exercises appeared less investigative and more demonstrative, designed to create the impression that a major terror network had been uncovered and, in the process, to justify the demonisation of Muslims across the country. When the NIA raided my home that year, I immediately recognised the script.

I later prepared an affidavit detailing everything that transpired during the raid, particularly after the agency refused to provide me with a clone copy of the seized digital material. I did not sign the panchanama. The officers informed us that they had instructions from Delhi and that if the door was not opened, it would be broken. There was no urgency grounded in evidence, only the calm confidence of authority acting on unquestionable orders.

The basis for the raid was fragile. My name had appeared in the phone of a person arrested earlier that year in a Popular Front of India (PFI) related case in Bihar. I told the officers what was true and verifiable, that I had provided legal advice. In any functioning legal system, the distinction between professional assistance in a specific instance and organisational association should matter. Here, it did not. The officers waited for several hours before finally entering, after a notice in my name was issued. What appeared to energise them was not the material before them, but the possibility that I could be fitted into a larger national conspiracy, perhaps even arrested. It was an opportunity they were reluctant to let go.

To this day, nothing has been proved against me, just as nothing was proved on two earlier occasions that nevertheless resulted in my imprisonment for nine years. Proof, however, is rarely the objective. The larger aim is to intimidate, to exhaust, and to signal consequences for writing, speaking, and working against state excesses. Arrest is not always necessary. The raid itself serves as a warning. Whether or not an arrest follows, there is no accountability for the manner in which power is exercised.

This experience was not an aberration in my life. It was part of a much longer continuum.

My first arrest took place in 2001, when I was still a student. I was active in my neighbourhood, engaged with local issues, and visible. That visibility alone was enough. Once your name enters police records, it rarely leaves. It follows you across years and across cases, creating a domino effect. That first arrest eventually led to my implication in the 2006 Mumbai blasts case. The logic was circular and deeply flawed. I was considered a suspect because I had been a suspect before.

This logic has not disappeared. It remains embedded in the system. It was visible recently in the oral remarks of Justice Manoj Oza while addressing students of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences who were accused merely of organising a poetry reading on the death anniversary of Saibaba. He remarked that their careers were ruined. The implication was clear. Even an act as modest as a poetry reading could destroy futures.

But can the fear of losing a career become the ultimate limit of conscience? Can one genuinely believe something is unjust and still decide to remain silent to protect oneself, one’s family, or one’s prospects? Any idea worth upholding demands sacrifice. To imagine social change without the willingness to bear its costs is to live in fool’s paradise.

Urdu Poet Amir Usmani, talks about this aptly;

ye qadam qadam balā.eñ ye savād-e-kū-e-jānāñ

vo yahīñ se laut jaa.e jise zindagī ho pyārī

(At every step, there are calamities in this dark lane of the beloved;

let the one who loves life turn back from here.)

As an undertrial prisoner, I had no space to campaign for the rights of undertrials. I was incarcerated myself. The moment I was released, I began speaking for my co accused. I repeatedly described the trial court judgement as flawed and urged the Bombay High Court to correct a serious miscarriage of justice. While I was relieved to regain my freedom, that relief was overshadowed by concern for those who remained convicted. Remaining silent would have meant accepting an outcome I could not morally reconcile with.

To be a Muslim engaged in public or legal activism in India today is to live with constant vulnerability. The community is already in a fragile position, and the state’s response becomes visibly harsher when dissent emerges offering legal assistance carries risk. Acts that are routine in other contexts, such as organising defence committees or publicly supporting prisoners, are treated as suspicious, especially when Muslims undertake them.

The consequences are evident. Many Muslim activists have been arrested and imprisoned. Some have withdrawn from public life. Others have sought safety by aligning with mainstream political parties. Very few have been able to continue independent work without interruption. The cost is simply too high.

For those who return from prison, the challenge is not only political but also deeply personal. Survival becomes central. How does one support a family? Who sustains a household while cases stretch across years? Who stands by when stigma becomes permanent? Without a support system, sustained activism becomes nearly impossible.

And yet, some continue. Not because the risks have diminished, but because withdrawal would mean accepting a silence imposed through fear. For many, returning to work is not a dramatic gesture. It is an act of endurance.

Abdul Wahid Shaikh is one of the accused in the 7/11 Mumbai Bomb Blasts, and is a lawyer, activist and author of the book 'Begunah Qaidi'

(Views expressed are personal)

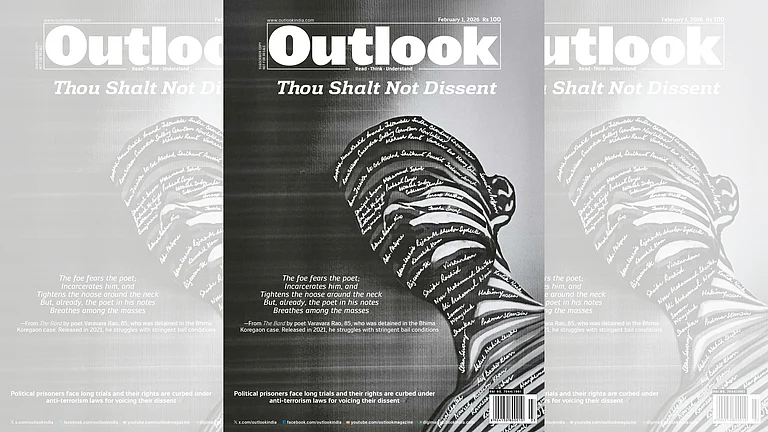

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)