Summary of this article

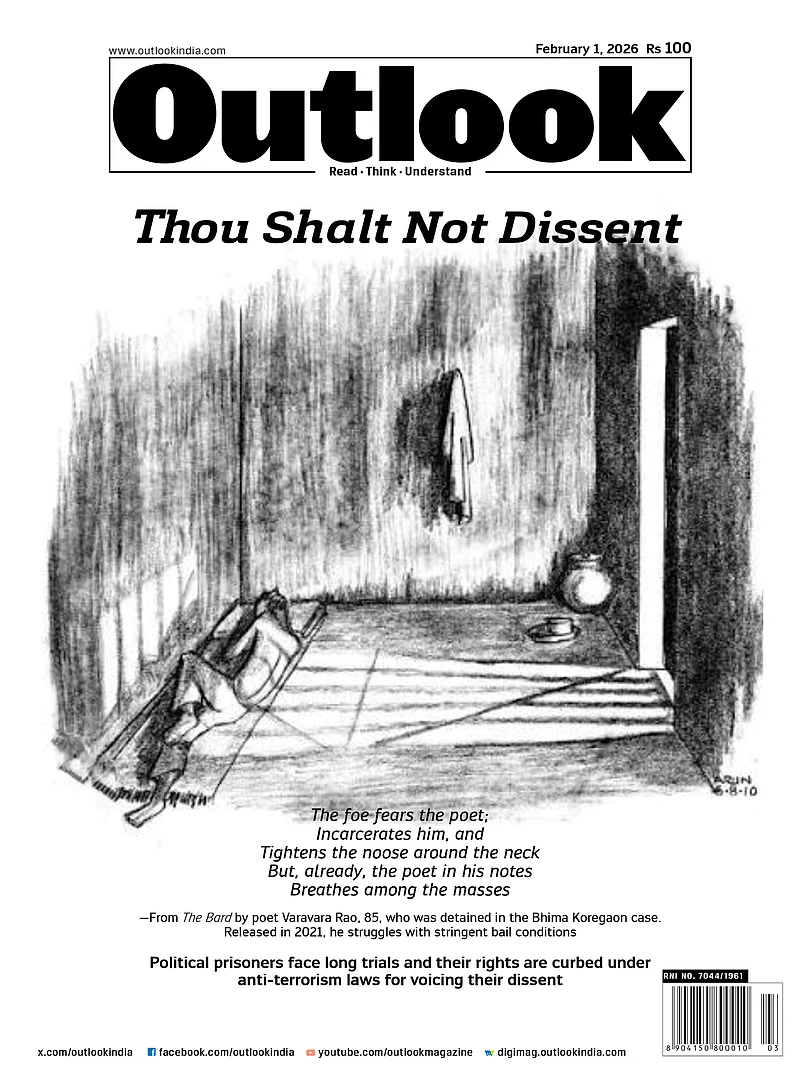

Outlook’s February 1 issue, Thou Shalt Not Dissent, chronicles life behind bars, the trauma, sights and sounds of a world bereft of freedom, normalcy and reason

Dissent in India has long been shaped by the UAPA and National Security Act

Activists like Umar Khalid, Gautam Navlakha, Sudha Bharadwaj, Hany Babu have lent their voices to the issue.

“I have questioned the validity, legality and justness of several steps taken by the government and the ruling class. If this makes me a ‘deshdrohi’, then so be it. We are part of the process. In a way I am happy to be part of this process. I am not a silent spectator, but part of the game and ready to pay the price whatever be it,” said Father Stan Swamy, an 85-year-old Jesuit priest and adivasi rights activist, who was arrested by the NIA in 2020 after being implicated in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence case.

The oldest person to be accused of ‘terrorism’ in the country, Stan Swamy passed away a few months later, a bail hearing pending, and life lost in suspension. Owing to his Parkinson's affliction, Swamy had requested for a sipper and a straw before his death, unable to hold a glass. The NIA had claimed they had not seized his sipper and straw and took 20 days to respond to the request of providing him with the same at Tajola Jail. For many, the delay was symptomatic of the conditions of political prisoners in the country, who still find themselves behind bars, or out on bail. Under the UAPA, a name is perceived as a threat against the sovereignty of the largest democracy in the world as life becomes subject to interpretation and living conditions malleable in the hands of the State.

In January 2026, scholars and activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam were denied bail on the grounds of being part of the ‘larger conspiracy’ in the 2020 Delhi Riots case, while other accused were granted the long-awaited release. The Supreme Court held that prolonged incarceration could not be treated as a ground for bail for the two implicated under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). From Tihar to Tajola, the UAPA, defined by controversy over its reach and extent, is not merely a burning headline, but a symptom of the Indian State, where the accused is never freed from the shackles, even if they find themselves outside the darkness of the gallows.

In Outlook’s February 1 issue, Thou Shalt Not Dissent, first-person accounts of political activists who were slapped with anti-terrorism charges under different political regimes, explore life behind bars, the trauma, sights and sounds of a world bereft of freedom, normalcy and reason. Weaved with the accounts are stories of individuals who carry the burden of incarceration like a tumour on the face, afraid to cover it, so it doesn’t chafe, and hesitant to let it free, so it does not translate into their only identity.

Dissent in India has long been shaped by the UAPA and National Security Act (NSA), two acts which have reduced multiple scholars, lawyers, priests and students to jail fodder under the indisputable claim of safeguarding the sovereignty and security of the State. Scathing indictments of the contentious laws have been launched following the arrests, triggering questions on the state of Indian democracy at large. Outlook’s issue stretches beyond the technicalities and rehearsed questions of determination, to assess the mental cost of incarceration, of spending days in solitary confinement, of processing the trauma of waking up to neutered hopes of countless fellow prisoners staring into the tortured blanks of the prison walls, and of taking life one ‘mulaqat’ at a time.

Activists Varavara Rao, Shoma Sen and Hany Babu -- all of whom were among the 16 arrested in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence case -- accused of inciting caste-based violence through the power of speech, now find themselves out of jail, but nursing a wound that refuses to heal. The issue shines a light on their voices torn by fear, the futility of hope, the numbness of bureaucratic drawl, and the memories of prison but still refusing to cower. The agony of Sonam Wangchuk, the activist who finds himself behind bars, charged with sedition for demanding the protection of Ladakh under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution, is voiced by his wife, who shares her husband’s experience in prison.

Umar Khalid narrates a moving account to Apeksha Priyadarshini of life after returning to Tihar following his interim bail, and the eventual rejection of bail in the apex court - being free as a state of mind, finding solace in little things, and sheltering realisation of how his arrest speaks of a larger malaise - of silencing voices that ask uncomfortable questions.

Anand Teltumbde and Sudha Bharadwaj pen intimate accounts of life after being imprisoned and released in the contentious Bhima Koregaon case. Bharadwaj chronicles her shift from being a trade-unionist and lawyer in Chhattisgarh to being strapped to the urban reality of Mumbai, where she continues to be monitored - trying to stay afloat in a city which is unfamiliar, intimidating but brimming with working class sensibilities. Teltumbde shapes his column in memory and resistance, of life in jail and its absurdities, and the long shadow that incarceration casts. Stringent bail conditions define the lives of the people released, much like Teltumbde’s. Students and friends shy away from maintaining contact, while any travel beyond Maharashtra even for academic pursuits is rejected.

Gautam Navlakha, also accused in the Bhima Koregaon Case, writes on life inside the prison, of grasping at survival but skirting around the strictures of jail life by indulging in little joys of singing and laughing aloud. He goes on to tether it to the reality of the experiential void and life after incarceration with severe constraints.

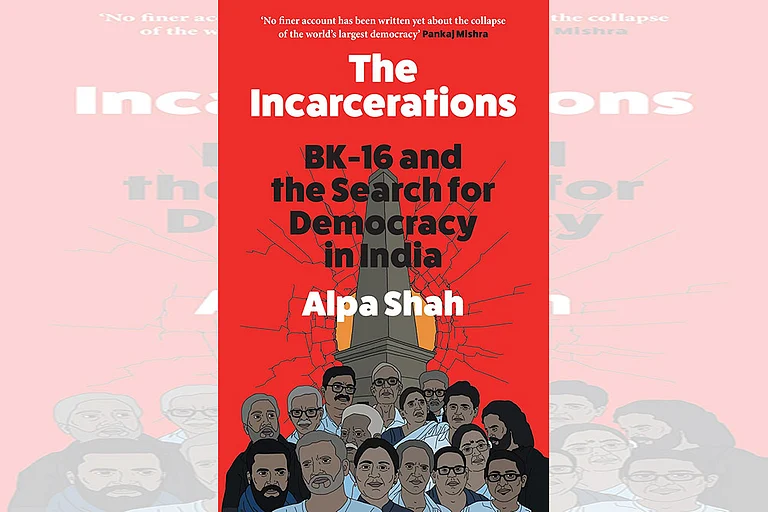

In addition, Outlook’s reporters dive into stories of people like Mohammed Iqbal and Ratiram Majhi, who despite being acquitted, see their lives crumbling down under the weight and memories of imprisonment. Independent researcher and author Sharmila Purkayastha, in her piece Inside the Phansi Yard, highlights the trauma of people on death row, who spent a decade in solitary cells for their role in the Mumbai suburban train blasts of July 2006. While they were pronounced ‘not guilty’ in 2025, the internal damage, almost inexplicable, speaks of a larger problem. Academic Radhika Chitkara writes on how criminal and security legislations are designed to systematically target Advasis, while Alpa Shah, in her column, details her experience of getting into depths of the Bhima Koregaon case while penning her book, ‘The Incarcerations’ and how fear was instrumentalised through the arrests to subdue voices capable of dissent.

The issue bears testimony to Outlook’s unrelenting search for truth in voices, resistance in memory, and holding a mirror to the politics of fear. Across gender, caste, creed, social status, these voices from prison speak loudly of the state of a democracy, standing at the precipice of its 77th year as a Republic. From the Emergency to the turn of the century and finally into the post-truth years, political prisoners continue to search for hope and light in dank, dark prison cells. Those out on bail or discharged remain shackled by society, trying to break past the immovable walls that were once tangible, and now more permanent in abstraction.

“Since, my friend, you have revealed your deepest fear

I sentence you to be exposed before your peers.

Tear down the wall,”

The Trial, Pink Floyd