Most inmates leave with much bitterness after doing time in “correctional homes”

Many inmates become critically ill due to bureaucratic procedures and rigidity, or the callousness of the jail administration

Friendships among women formed in the period of their incarceration continue outside the prison walls, as such abandoned women provide housing and financial help to each other

Though it is true that I did time, it appears more as if time did me. One cloudy evening, on June 21, 2018, when I was being taken to the Yerawada jail in Pune, I knew that watches were not allowed in jail, yet I had clung on to my basic Titan watch. I had to submit it at the gate. It was returned to me, looking like a museum relic, almost six years later. Time, trapped in a brown sarkari envelope, sealed in a metal box. Time that had stopped ticking.

I was only a few hours into jail, but the woman who was in charge of me, my warder, had done 22 years. As I was entering jail, she was preparing for her release. Yet, each day, time passed in the same way for each of us. The gong rings at five to wake us up. Second bell at six; you sit for the morning headcount and wait for the guards and officers to come on their round. Somebody sings the Marathi bhajan, “ughada daar O Deva” (open the gates, O Lord), and everybody laughs as the “madam” with the huge bunch of keys shouts: “thaamb, thaamb, ughadto” (hang on, we’re opening). Because tea, breakfast and milk are brought to our barracks by the canteen workers, we know that it must be seven. We are free now, within the high compound walls, edged with barbed wire. We can walk around the garden, walk to the bathrooms, line up under the tamarind tree for hot water, sit in the lawn and chat with friends, wash our clothes and dry them in the assigned places, collect our morning meal in the battered aluminum dishes like beggars and return to our barracks.

This is also the time when things “come”. “Dawakhana Alaaa!”, comes the shrill call of the kaamwali from the gate, announcing that the doctor and dispensary have come (though the latter always remains in one corner of an office room). Mulakat or personal meetings come, canteen comes, clothes from the family come, the library comes and wonder of wonders, the court comes. That means that the van transporting prisoners to court has come and we have to queue up to display our bare bodies before we exit the jail. The nicest, of course, is when chicken comes, or pakoras or fruits.

So, we are different tribes living in different villages (barracks) and the Tom Toms, or shouting kaamwalis, are our primitive form of communication. At 12 noon, the gong rings again, and it is time to go into the barracks and be locked up for resting. At 3, the gong tells us that it is time for tea. At 5 pm, we are relieved to learn that another day has passed as the bell herds us to our temporary homes. Counting is done and declared by a final bell count. Like Robinson Crusoe, stranded on his island, we can cut another notch on the branch to mark our passing day.

The night has no time. If you suddenly wake up from a bad dream, which is often, you have different ways of guessing. You might be able to hear the gong counting the hours, from the men’s jail, right across the road. Or you might hear the milk van entering the jail and the night guard shouting to wake up the canteen staff, so you would know that it is between 3 or 4 AM. At the Mumbai district women’s prison in Byculla, there were a few clocks hung on the walls outside the barrack doors. I remember a new prisoner, a flustered educated middle-class woman, getting up every hour the whole night to walk up to the door and peer at the barred time. “Why do you need to know the time?” the warder asked her. “It just passes at its own speed. You can’t make it go faster or slower.”

For me, the initial months went the slowest, but later, especially after shifting to Mumbai, time in jail passed quite swiftly. This does not mean that the anxiety or despair was less; it was just that I was getting more habituated to jail life. It took time to get used to jail time. I measured time as periods from mulakat to mulakat, one court date to another, or the filing of each bail application and its progression and final rejection. Each time an application was filed, there was a little excitement and hope in one’s mind.

The mulakat with lawyers and relatives, or the phone calls with them during the COVID pandemic, gave one hope. The applications were very well drafted, the hearings well argued and though, at the back of one’s mind, one knew that chances of bail were dim, the hope pushed time a little forward. We all felt great for Sudha Bharadwaj, who had been granted default bail on December 1, 2021. The same for eight of us was rejected. When some lawyers assured us that we, too, would soon be out, it felt that release time was just around the corner. But soon, I realised that one or two weeks in jail time meant one or two years in court time.

What appeared to us as a waste of time was especially pathetic when it came to health issues. That due to such denials and delays, Stan Swamy lost his life and Varavara Rao was virtually at the brink, are well-known facts. Not just those accused in our case, but many other inmates became critically ill due to such bureaucratic procedures and rigidity, or callousness of the jail administration.

In Byculla, every year, we saw at least one prisoner lose her life. Sometimes, the immense anxiety that jail life causes led to panic attacks among the prisoners, which resembled heart attacks. Spending an entire night with a fellow prisoner wheezing and gasping for breath, rolling up her eyes, body limp and cold, was torture for the entire barrack, as we spent hours calling for the doctor or guards.

Though Yerawada Jail had a doctor on the premises and an ECG machine, Byculla did not. No doctor came to attend a serious patient at night and the jailer had to be consulted over the phone. If she granted permission, the gate was opened and the patient taken to J.J. Hospital. If there was a power breakdown in the night, it would be a suffocating experience without fans, with the stench of sweat and sense of claustrophobia spreading from barrack to barrack. While Yerwada Central Jail had a generator that would immediately be switched on, it was the Byculla jail, situated in the Maximum City, in South Bombay, where even slum dwellers had inverters, that had absolutely no alternative, not even an emergency light.

There is a conception among prison inmates that when a person gets bail, his or her co-accused would soon be granted the same, on parity. But there is no saying when that will happen, as it could be after six months or six years. For example, though many have been granted bail in the Bhima Koregaon case, advocate Surendra Gadling’s incarceration has crossed seven-and-a-half years. There are inmates who secure bail, hoping to be released in a month’s time, but not being able to arrange “surety” (bail money or somebody to stand guarantee), languish in jail for years.

In the unfortunate circumstances of a conviction, the irrationality of the time span accorded in the sentence drives inmates to despair. Many women accused of murder may, in reality, be victims of sexual abuse or domestic violence, where murder was a desperate act to flee from the situation, or due to self-defense. Yet, the minimum punishment for what used to be Section 302, is a life sentence, but the time span of “life” is not defined. Though a life sentence used to be 14 years, it is now assumed to be till the end of one’s natural life, though this is usually condoned after 20 years. Now, having waited for justice for six or seven years (the average time for a murder trial to be concluded), the convict would have to wait for release for 15-20 more years.

If we were to ask, what has doing time in these so-called “Correctional Homes” done to prisoners, we would find that most inmates leave with much bitterness. I have heard women mutter that they have been imprisoned for no fault of theirs and after leaving, they would really commit some crime. Many women who have been accused of murdering their husbands but were acquitted are now estranged from their families, especially their children. They despair that even to work as domestic workers, a background check is often done, which will prevent them from gainful employment.

I found that friendships amongst women formed in the period of their incarceration have continued outside the prison walls, as such abandoned women provide housing and financial help to each other. Being political prisoners, the joy that we felt when released, on uniting with family and friends, and our acceptance in the community, is an anomaly for many other women prisoners on their release. Most women have entered the hell-holes called prisons because of the socio-economic dimensions of crime, the huge disparities between people based on class, caste, gender and religion and without addressing these issues of social justice, justice cannot be delivered during these times.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Shoma Sen is a women’s rights activist and assistant professor and was head of the English literature department of the Nagpur University. On June 8, 2018, she was arrested by the Pune Police for her alleged involvement in the Bhima Koregaon riots

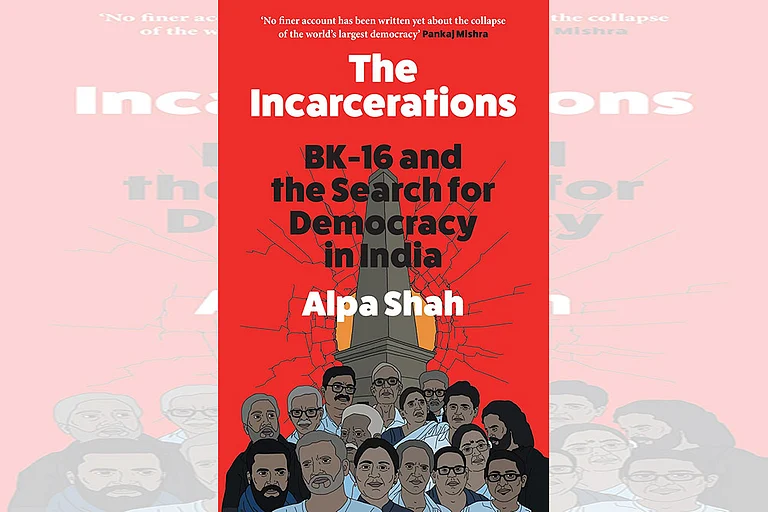

Violence erupted on January 1, 2018, during a Dalit commemoration of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon’s 200th anniversary, resulting in one death and multiple injuries from stone-pelting and arson. Tensions stemmed from caste hostilities, with the speakers at the Elgar Parishad event probed for incitement.

Investigators named several activists in connection with the Elgar Parishad event. The celebration commemorates the 1818 battle, seen as a symbol of Dalit resistance.

Key arrests included Sudhir Dhawale and Jyoti Jagtap, followed by activists such as Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, Mahesh Raut, Rona Wilson, Sudha Bharadwaj, Arun Ferreira, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao and Gautam Navlakha.

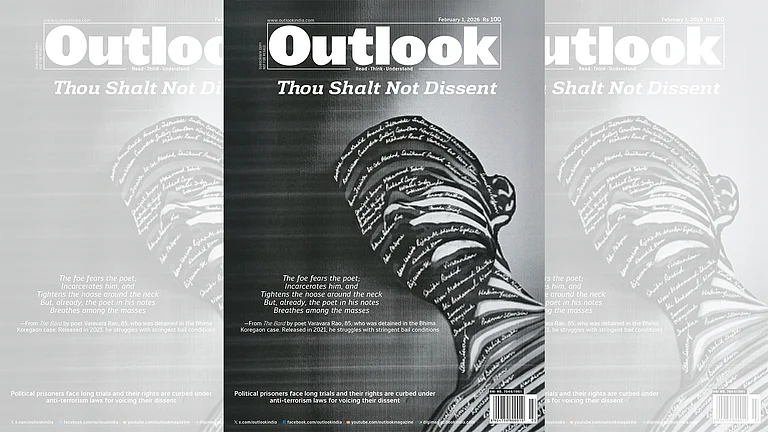

(This article is part of the Magazine issue titled Thou Shalt Not Dissent dated February 1, 2026, on political prisoners facing long trials and the curbing of their rights under anti-terrorism laws for voicing their dissent)