“Raghupati rāghava rājārāma,

patita pāvana sītārāma

sītārāma, sītārāma,

bhaja pyāre tu sītārāma

īśvara allāha tero nāma

saba ko sanmati de bhagavāna

rāma rahīma karīma samāna

hama saba hai unakī santāna

saba milā māṅge yaha varadāna

hamārā rahe mānava kā jñāna”

In October 2021, a viral clip of a music performance by singer and BJP MP Hans Raj Hans went viral. In the video, the singer was seen performing the Viahsnav bhajan “Raghupatai Raghav Raja Ram” on a stage. But instead of singing the lines “Ishwar Allah tero naan, sabko sanmati de bhagwan” as Mahatma Gandhi wrote in the second couplet of the song’s first stanza, the singer could be heard singing the phrase interchangeably with “Jai Shri Ram, Sita Ram”. A fact check by India Today revealed that the modified version of the song was sung on October 4, 2021, on the occasion of the 152nd birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi at Gandhi Smriti. While the singer did sing the line “Ishwar Allah tero naam” a few times in the song, he also repeatedly sang the alternate line “Jai Shri Ram”, which is not part of the original Bhajan.

The incident led to outrage against the singer as well as the BJP on social media for trying to erase the tenet of communal harmony that the song espouses. But the song, which once used to be a staple in Bollywood films across genres, seems to have all but disappeared from popular recreations.

Secularising 'Ram Dhun'

Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram, also known as “Ram Dhun”, is a bhajan (prayer song) that was widely popularised by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Noted Hindustani classical musician Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, who founded the prestigious Gandharva school of music in 1901, composed the music of the bhajan and was the first to sing it in its present iteration.

Gandhi, however, is not the original writer of the bhajan, which many legends have ascribed to either Tulsidas or as being a derivative of his Ramcharitamanas. The 17th-century Marathi poet-saint Ramdas has also been credited by some sources for penning down the verse. Versions of the Ram Dhun existed for years before Gandhi arrived on the scene in colonial India and began mobilising masses against British rule. His movement against the British was a secular one and needed support from Hindus and Muslims of India. Thus Gandhi introduced the modified line “Ishwar Allah Tero Naam, sabko sanmati de bhagwan” (Ishwar and Allah are both your name, oh God, please rain good sense on all) in the song to make it more appealing to the mixed masses, and to project India as a composite front made of both Hindu and Muslim identities working together to fight off the yoke of British colonialism. The lyric basically meant that the “Ishwar” that Hindus worship or “Allah” that Muslims worship was one and the same in a bid to project Hindus and Muslims not as warring factions but as a unified front fighting on the same side for freedom of India.

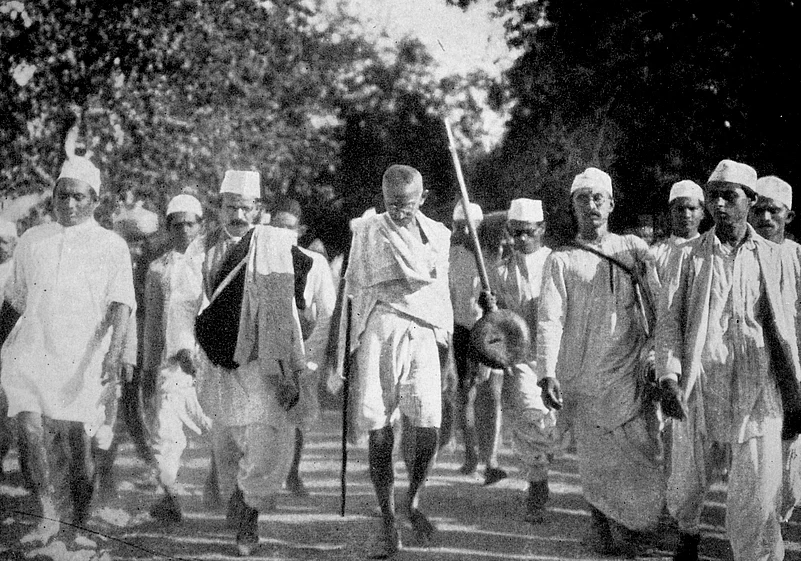

The song was sung during the 1930 Dandi March led by Gandhi and his innovation was readily accepted by the masses.

Through such innovations, Gandhi managed to provide a new vision of Ram, the Hindu deity at the forefront of national Hindutva political narratives in India since the turn of the 20th century. In the 2015 paper titled ‘Apne Apne Ram: God in Politics’, researchers Navneet Sharma and Pradeep Nair write that the image of Ram projected by Hindutva icons like MS Golwalkar was an out-and-out “Hindu god”. As an incarnate of Vishnu, Golwalkar’s Ram is the most important of the Hindu mythology triumvirate on Earth, consisting of the Creator (Brahma), Preserver (Vishnu), and Destroyer (Mahesh/Shiva). Gandhi’s Ram however “stands out as a benevolent king/or the philosopher king whose rule accommodates every different being of his populace”, Sharma and Nair note. He was "secular, divine, and spiritual”.

In literature and correspondence authored by Gandhi, he repeatedly stressed the secular nature of the "Ramrajya" (Ram's empire) that he had been demanding as opposed to the British Raj. In a February 26, 1947 dispatch in Harijan, for instance, Gandhi categorically reiterated that people should not “commit the mistake of thinking that Ramrajya means a rule of Hindus”

“My Ram is another name for Khuda or God. I want Khuda Raj which is the same thing as the Kingdom of God on Earth,” Gandhi wrote.

Gandhi’s iteration of Ram Dhun not only fired the imaginations of Indians during the Indian freedom struggle but also in later phases of India’s political development.

A clear indication of the popularity of the bhajan’s verses can be traced in the repeated usage of the song lyrics in Bollywood films, one of the biggest drivers of behaviour change in India with the power to attract and influence the masses. This was especially true in the post-partition era.

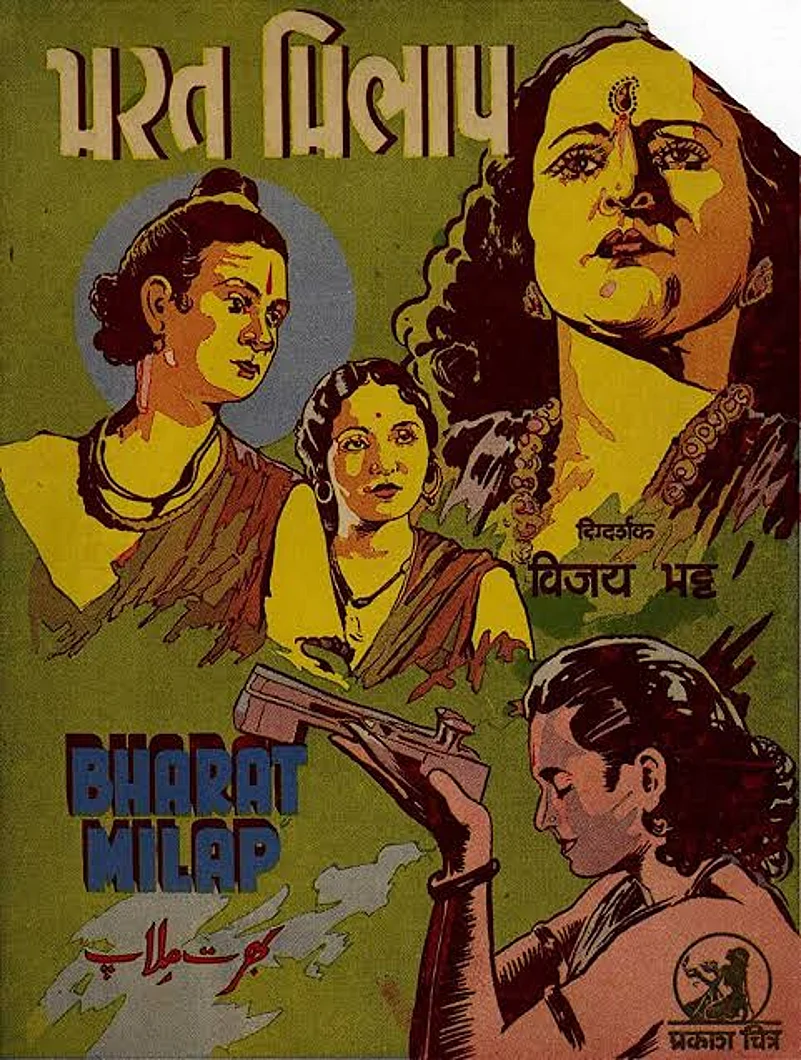

One of the earliest versions of the song used in Bollywood appeared in the 1942 film Bharat Milap. Since then, it has appeared several times in films like Shri Ram Bhatt Hanuman (1948), Jagriti (1954), Purab Aur Pashchim (1970). Millennials were also exposed to the song when actress Rani Mukherjee’s swanky, college-going Tina sang Gandhi's bhajan to impress Shah Rukh Khan’s Rahul in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998). In it, director Karan Johar even featured a remixed, funk rap version of the song in the second half of the film. Sung by the second female lead, Kajol, the song symbolises a moment of “homecoming” of the older Rahul and perhaps the use of the bhajan is meant to evoke the imagery of Ram returning home from vanvasa and finally becoming one with his beloved Sita.

The fact that the bhajan made it to a film about a college romance and coming of age featuring a love triangle, a Muslim actor as the lead at a time when capitalism and globalisation were knocking on India's doors perhaps points to the universality of the bhajan and its wide cultural appeal and acceptance. It's also a nod to the international market for the song. In the film, Johar shows a group of zonked-out hippies sporting peace signs that are signing the song. It's perhaps a nod to its popularity during the "flower power" movements for peace in the 60s and 70s in Western countries like the US and UK. This is evident from the fact that Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram made it to the 1964 album named "Strangers and Cousins" by iconic American country singer and social activist Pete Seeger.

Juxtaposition of 'Ishwar' and 'Allah' in Bollywood songs

Gandhi’s innovation may have inspired several generations of lyricists that emerged in India in later decades as the Indian film industry matured. Following independence and the bloody partition, Hindu-Muslim relations became one of the central themes of films and after a tense decade, the initial stream of films that were produced post-partition reflected a strong sense of Hindu-Muslim harmony. It was as if the writers were trying to soothe the bleeding cracks of a nation divided on religion with the balm of poetry and the comfort of a shared future of peace and love.

Such optimism is clear in lyrics like ‘Tu Hindu banega na Musalmaan banega, insaan ki aulaad hai; insaan banega”, written by Sahir Ludhyanvi for the 1959 film ‘Dhool Ka Phool’ made a decade after the partition emphasized the importance of humanity over religion.

Ishwar and Allah have been juxtaposed several times by others. Filmmaker Deepa Mehta’s critically acclaimed Earth (1999), features the song “Ishwar Allah”, composed flawlessly by AR Rehman, in which lyricist Javed Akhtar questions the need for communal disharmony in India. The film evokes the disquiet of the Partition era to reflect on questions and prejudices that continue to divide communities between India today.

The juxtaposition also shows up in Pukar (2000) when Lata Mangeshkar sings the soulful lyrics written by Majrooh Sultanpuri, “Hey Ishwar, ya allah, ye pukar sun le”. Appearing in the climax scene of a film that glorified a wrongfully accused Indian army man, who works alone to bring down a terrorist plot by Pakistani agents, the song perhaps tries to invoke communal harmony in the aftermath of the Kargil war, a call for peace to both communities by calling on the gods of both people. Even in the rather short-sighted film about Indo-Pak rivalry which reductionists pitch not as a geopolitical struggle but as a fight between Hindus and Muslims, the song stands out as a boastful reminder of India’s secular credentials.

Such instances of communal harmony in popular, mainstream Bollywood songs and lyrics are fast disappearing from Hindi films. In fact, both Ishwar and Allah have been replaced by vociferous volleys of “Jai Shree Ram” or "Jai Mahadev" as exhibited by Hans Raj Hans and countless Bollywood songs of this year. The 2022 film Ram Setu featuring Hindutva poster boy Akshay Kumar in a desi Indiana Jones-like avataar (only the Arthurian Holy Grail is replaced by legends of Ram) contains a song called “Jai Shree Ram” (yes, it's that direct) by lyricist and screenwriter Shekhar Astitwa.

The suggestively named song “Kesariya” in the Ranveer Kapoor-starrer Hindu fantasy fiction extravaganza Brahmastra (2022) also contained songs heavy with Hindu mythological imagery. While the song is yet another iteration of the same old love song and dance sequence between the hero and the heroine, Kesariya adds unnecessary Hindu overtones to the song by adding visual motifs of temples, Hindu ritual practices taking place in the backdrop of the holy city of Varanasi, a politically and religiously significant city in India and the site for a new mandir vs masjid fight after Ayodhya.

Not just Allah, but even other indicators of Muslim identity such as Urdu words and sounds are slowly fading out of Hindi songs.

Several artists including lyricists like Gulzar and singers like Asha Bhonsle have spoken in media interviews about the decline in correct Urdu pronunciations and sounds in songs and films. It is said that singer Lata Mangeshkar took lessons in Urdu so that she could pronounce the words and produce the epiglottal sounds associated with Urdu with precision. Irrespective of the artist's religious background, the proper usage of Urdu was seen in Bollywood as part of artistic integrity.

In the paper “My name is Khan… from the epiglottis: Changing linguistic norms in Bollywood songs”, Rizwan Ahmed notes how the usage of proper Urdu words and pronunciations declined in the films that were produced by Bollywood in the 90s onward. While there is no provable correlation, the decline in artists’ exhortation of Urdu and its specificities in favour of more Hindi-ised sounds and words coincides with the rise of ultra-Hindu nationalism in the country.

Today, popular Bollywood singers like Shreya Ghoshal, Arijit Singh, Alka Yagnik (those has been around for decades) are more inclined to sing Urdu words in the Hindi phonetic style. The decline of Urdu pronunciations and the importance of the language in film lyricism reflects the overall decline in the Urdu language in India, which has in recent decades suffered communal onslaughts due to its unwitting association with one community.

In truth, a repertoire of lyricists that worked in the golden period of the Indian film industry post-independence include lyricists and poets both Hindu and Muslim who were adept at both Hindi and Urdu. Actors prided themselves in having knowledge of Urdu literature and legends like the Abbottabad-born Manoj Kumar would write their scripts in Urdu. Such religious and cultural intersections, confluences and synergies in popular art and culture are fast becoming a thing of the past.

Hindutva and the Underground Music Movement

In the years since 2014, the country has seen the rise of alternate, crude, ultra-religious musical subgenres of "underground music" like “Hindu trance”, “Hindu trap”, “Hindu pop” and others that are today played across the public events and celebrations such as Kanwar yantras, election rallies, and even Hindu satsang events. Sociologists, political commentators, and art historians have construed this trend as a direct attack on the secular nature and history of Indian lyricism and music. Easily classified under the wider umbrella of “Hindutva pop” or "saffron pop", these soundtracks mix techno and dance beat with violent and communal lyrics invoking inter-community violence and hate. The songs frequently feature heavy invectives against Pakistan, amplify the supreme power of Hindu gods like Ram, and use problematic communal slogans and catchy hooks to captivate audiences.

Produced with a pitiably low budget as opposed to Bollywood songs, these songs are disseminated via internet platforms and often contain calls for violence against minorities hidden under the sheen of pop dance beats. Singers like Sanjay Faizabadi and Laxmi Dubey command large fan followings by performing such content.

Recent songs by Bollywood seem to show that the industry is now trying to catch up to these regional and "underground" music trends. Instead of putting its weight behind its secular historical background, Bollywood also seems to be legitimizing these perverse and politically motivated songs by making their own musical versions of soft religious propaganda disguised as an innocent Bollywood "song and dance" sequence. Case in point are songs like Ram Setu's "Jai Shree Ram" or "Shiva theme" from Brahmastra.

The current trends in music are indicative of the erosion of the secular notions of the Ganga Yamuna tehzeeb, a composite confluence of Hindu and Islamic influences, sensibilities and mannerisms that shaped what we understand as “Indian art" and defined the country's artistic aesthetic and cultural ethos. Once an epitome of harmony and synthesis, Bollywood music and lyrics have become yet another arena for majoritarian religious muscle flexing. While aiding the visions of Hindu grandeur projected by the current dispensation, songs in Bollywood today are in their own way adding to the invisibalisation of Muslims and erasure of their cultural contributions to the identity of India.