August 4, 2025 marks Kishore Kumar’s 96th Birth Anniversary

Kumar, as a rebel in the industry, defied norms and carved his own niche

Kumar’s tumultuous life and legacy sustained beyond his death, giving rise to biopics and AI-generated song renditions

It’s a familiar arc—to scoff at parents clinging to their zamaane ke gaane, only to find oneself returning to the same tunes years later. But Kishore Kumar’s music doesn’t just signal nostalgia—it collapses time. It draws you back to the first moment you heard it, likely from a parent’s stereo, but it also disarms you in the now. There is power in its lingering, not just because of a romanticised past or lyrical depth alone; it’s the voice—one that accesses emotion at its barest. For generations of lovers, insomniacs and solitary commuters on public transport, he has become less a singer, more a companion. Listen to “Zindagi Ek Safar Hai Suhaana” (Andaz, 1971) or “Chala Jaata Hoon” (Mere Jeevan Saathi, 1972) and it’s impossible not to map your present onto it—joy, absurdity, restlessness and dread—all coexisting.

The cheer of his rhythm and whistle dances dangerously close to despair in perhaps a line like “Yahaan Kal Kya Ho Kisne Jaana.” Kumar doesn’t offer escape. The cheer stays on the surface, but underneath, it’s life as it is: unknowable, fleeting, oddly beautiful. A song like “Yeh Shaam Mastani” opens with the lightness of leisure, yet seeps into a quiet ache that betrays the mood it sets. “Kuch Toh Log Kahenge” may seem like an anthem of carefree surrender, but it leaves the listener with a quiet sting, an aftertaste of something unresolved. Even Kumar’s entry into music reads like a fable—his voice shaped not by talent alone, but by injury, by accident. As Ashok Kumar recalls, he wasn’t born tuneful. It was relentless crying after injuring his toe that shaped his breathwork, made space in his lungs, refined his voice. His pain quite literally carved his art.

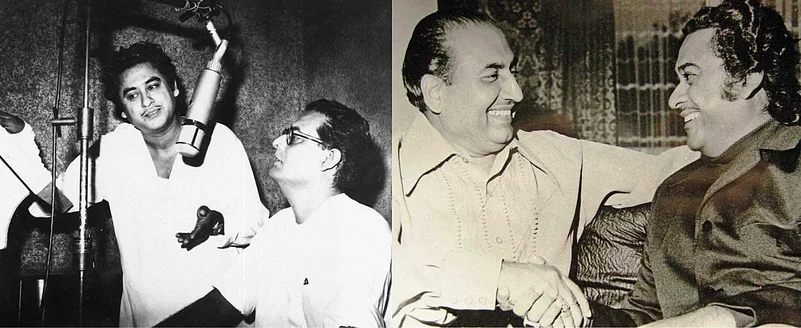

Ashok, an established actor himself, also coaxed him into acting in Shikari (1946), birthing his new identity—Kishore Kumar was no longer Abhas Kumar Ganguly. Amid several unmemorable roles, Kumar later collided with his comic brilliance in films like Ladki (1953), Naukri (1954), Rukhsana (1955), and Bhagam Bhag (1956), each sharpening his flair for mischief. However, one shouldn’t mistake his comedy for frivolity but rather a tool of subversion. What began as a feeble imitation of KL Saigal became the gateway to Khemchand Prakash, who gave Kumar his first major song in Ziddi (1948). It also marked the genesis of his lifelong bond with Dev Anand, who came to rely on him as his unmistakable singing voice. Though his heart was set on playback singing, his reluctant detours into acting, composing and direction sculpted him into one of the most eclectic forces in Indian cinema. But it was SD Burman who redirected Kumar from mimicry to invention, unlocking a raw, experimental sound that felt entirely his own. Influenced by Jimmie Rodgers and his yodels, Kumar found not just style, but self.

To be an artist, especially a memorable one, demands a distinct constellation of quirks, ideas, temperament, and skill that set one apart. Kumar stands as a relentless disruptor of the rigid machinery governing playback singing. From his flamboyant attire to his complete lack of formal training, he shattered norms, famously lending his voice to both male and female parts in “Aake Seedhi Lagi Dil Pe Jaise” from Half Ticket (1962). Kumar also wore his unrefined tendencies with pride in his music. A crack in the voice, skipped words, or improvised phrases—all added to a lived-in authenticity. Kumar is also notoriously known for turning up in disguises, sharp mimicry and climbing up trees to record songs. He never surrendered his madness to convention. His music never bowed solely to refinement; it reveled equally in playful chaos, evident in tracks like “Ek Chatur Naar”, “Eena Meena Deeka”, and “Hum The Woh Thi”. During the Emergency, Kumar declined to lend his voice to state propaganda. The government retaliated by blacklisting him, erasing him from All India Radio and Doordarshan. But Radio Ceylon refused to comply. His songs continued to play and sharpened public hunger. People tuned in with greater urgency, making his absence elsewhere even louder. When the Emergency lifted, the state couldn’t afford to ignore him anymore. Kumar hadn’t just survived censorship, he had actually rendered it irrelevant.

Revered playback singers such as Mohd. Rafi and Mukesh projected a masculinity marked by refinement, passion, stoicism, or swagger. Kumar, however, introduced a refreshing vulnerability—one that embraced silliness, desperation, self-deprecation, and lovesickness without losing its verity. In a song like “Humein Tumse Pyaar Kitna”, it is quite plainly Kumar’s raw heartbreak and its unravelling. In lively numbers like “Chhod Do Aanchal” or the playful “Ek Ladki Bheegi Bhaagi Si”, he remains unmistakably himself while fully surrendering to the emotional tides. This blend of candidness and charm feels like a precursor to the performative vulnerability in many male pop singers today, though those efforts often lack Kumar’s depth and impact.

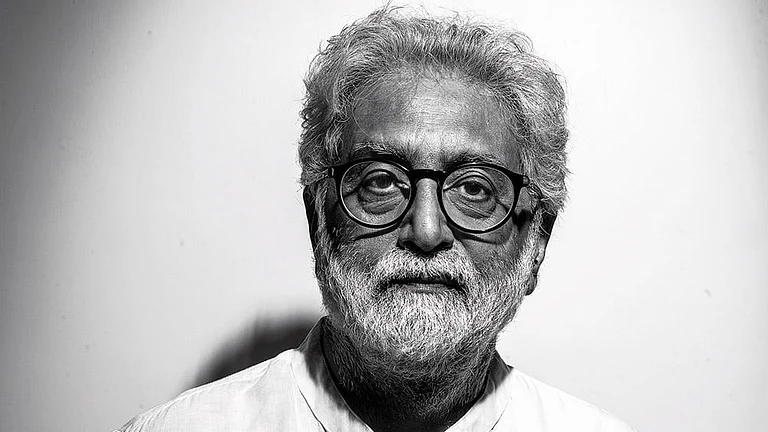

For a singer who crafted an entire lexicon of love and loss, Kumar’s own romantic life unfolded with equal abandon: chaotic, volatile, and never textbook. Kumar’s multilingual repertoire in Assamese, Bengali, Marathi and more gave his music a cultural texture that reached beyond Hindi cinema. It drew in regional listeners, each finding something familiar in his voice. That reach thus contributed to building him up into a pan-India icon. Much like his rebellion against industry norms, he refused to package his personal life into neat timelines or tidy resolutions. Each marriage unlocked a new version of him. Ruma Guha Thakurta was musically attuned to him, but his eccentric rhythm proved difficult to live with. Madhubala, his most iconic partner, brought to the relationship a fragility shaped by illness and longing—the same aching softness that would later echo in his voice. With Yogeeta Bali, the union felt momentary, like a refrain that didn’t quite fit the composition. His final marriage to Leena Chandavarkar, despite its visible dissonances, endured. Through them all, Kumar remained defiantly uncontained. His tumultuous life has long haunted director Anurag Basu, compelling him to return to it over and over. A biopic on Kumar remains the filmmaker’s most elusive yet persistent dream. It isn’t just the story of a man—it’s the impossible task of capturing chaos, brilliance, and defiance without flattening it.

Kumar suffered a heart attack in 1981 and spent half a year confined to bed. But true to form, he was back on stage soon after. In Assam the following year, a tarot reader declared publicly that he had only seven years left. That’s exactly what he got. On October 13, 1987, while planning a birthday party for his brother Ashok Kumar, he collapsed around 4:30 in the afternoon and died instantly. He was 58. Hours earlier, he had joked about his own death to Leena, as if rehearsing a final punchline. His last act, perhaps, was still rooted in instinct — to gather everyone and leave them laughing.

Across more than two thousand six hundred songs, Kumar’s legacy lives on, but maybe not in the way it should. For many new-age listeners, his music has moved beyond fandom practices into the realm of unnecessary artistic alterations. Kumar’s voice, now fed into AI models to “perform” renditions of tracks like “Saiyaara”, “Kaun Tujhe”, or “Ajab Si”, has become something users can summon on demand. The pull lies in hearing what “Channa Mereya” or “Kesariya” might have sounded like in his tone—because he could have, and he would’ve done it better. There’s a strange kind of power in being able to direct his voice anywhere we please, but what exactly are we commanding? These AI-crafted vocals often hover in the uncanny valley: eerily close, never whole. For tech creators and record labels, it’s novelty, virality, clickbait. But what gets lost in this simulation is the very core of what made Kumar magnetic. What once flowed from a place of instinct and imperfection is now reduced to code. The artist no longer leads; the audience does. Despite the bastardisation of his voice, perhaps his vast body of work is already enough. His voice carries its own weight, and maybe it needs to be left alone, remembered as it was. The constant urge to commemorate an artist often turns into exploitation, dulling their legacy instead of honouring it. A voice like Kumar’s doesn’t ask for reinvention. It demands to be heard, not reworked, and certainly not reframed into some forced intimacy that strips away the mystery.