1. Dharmendra’s song sequences were defined by subtlety and emotional gaze rather than dance, relying on close-ups and understated physicality to create intimacy.

2. His musical appearances trace his evolution in Hindi cinema—from shy newcomer to romantic hero, action icon, and eventually the sentimental patriarch.

3. His death at 89 has renewed appreciation for his most memorable song moments, including his quiet, haunting presence in Khamoshi (1969), which showcased his ability to evoke longing without dominating the screen.

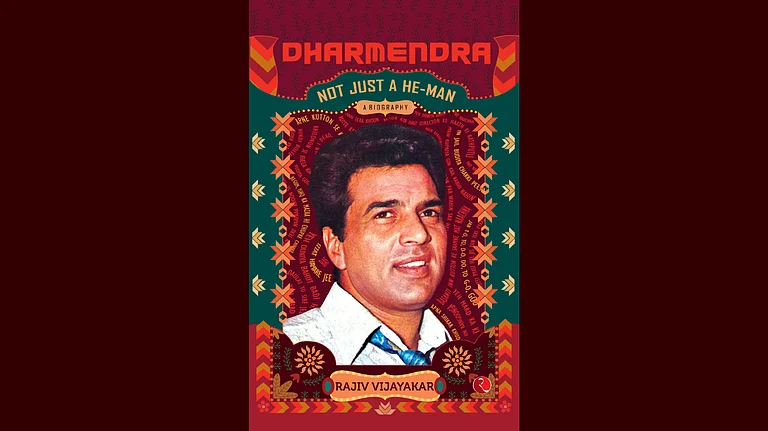

Unlike his contemporaries, Dharmendra was never a dancer in the classical filmy sense. He didn’t thrust like Jeetendra or glide like Dev Anand nor did he woo with Dilip Kumar’s tortured longing. Instead, songs on Dharmendra played out like scenes interrupted by music where the gaze did most of the work. Directors often framed him in close-ups, letting the softening of his eyes do most of the heavy lifting. Even in the rare moments of exuberance, it was the looseness of his body, not precision, that seduced audiences. This subtlety made his song sequences feel intimate.

For an actor remembered primarily for his physicality, his songs can easily map the man Hindi cinema made of him—from the shy Bimal Roy find of the early ’60s, to a romantic lead, to the action star who became a national obsession, to the ageing hero who endured stretches of irrelevance. In the recent decades, Dharmendra finally graduated into becoming the sentimental patriarch in the public consciousness.

News of his death, at 89, has reopened an archive of melodies and memories for old fans and young. When I asked my parents what their favourite Dharmendra songs were, both of them named “Woh Shaam Kuch Ajeeb Thi” before adding that it primarily belonged to Rajesh Khanna and Waheeda Rehman. Still, they insisted, Dharmendra’s presence left an impression. Written by Gulzar and composed by Hemant Kumar, this one was sung by Kishore Kumar. Dharmendra’s appearance in Khamoshi (1969) was striking. He was playing the part of a barely-visible emotional cipher. For an A-list male star to take such a quiet, almost ghostlike role was unusual in an era defined by showmanship and ego. His face appears and disappears like a memory, establishing early on that Dharmendra could evoke longing without dominating the frame.

By the 1970s, when he had become the industry’s definitive everyman-adonis, his songs expanded in scale. Sholay’s (1975) “Yeh Dosti” stands as Hindi cinema’s ultimate ode to friendship. In a song defined by its buddy dynamic, Dharmendra’s expressiveness, his easy warmth, his physical immediacy anchored the mood. Written by Anand Bakshi and sung by Kishore Kumar and Manna Dey to R.D. Burman’s rollicking composition, the five-minute song sequence took a staggering 21 days to shoot. Ramesh Sippy kept re-shooting parts of the film, including this song, which became a cultural anthem. Intriguingly, the dialogues of Sholay overshadowed its music at the time, leading to the release of vinyls featuring only spoken lines, an oddity in Hindi cinema at that time.

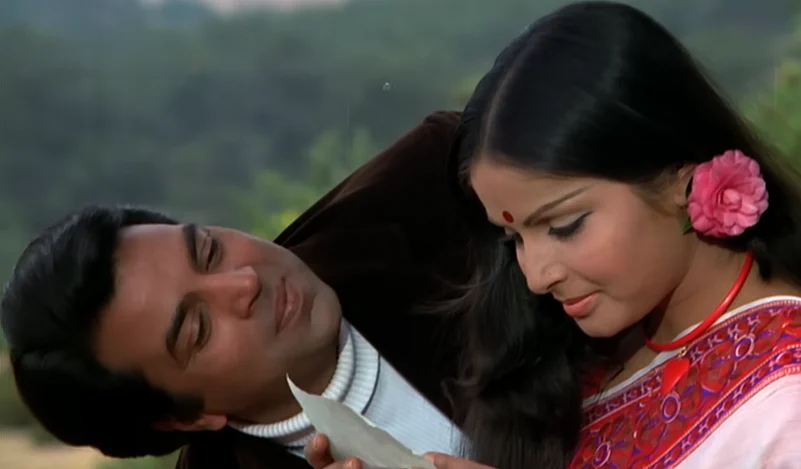

Dharmendra’s most enduring romantic imprint lies in songs like “Pal Pal Dil Ke Paas”, the floating Kishore Kumar ballad from Black Mail (1973). Composed by Kalyanji–Anandji, the track frames him amid pine trees and soft light, his face open in a way few macho stars allowed themselves to be. There was a reason Dharmendra became the fantasy of millions. This was long before he re-branded his image to become Bollywood’s “He-Man”.

Even his lighter songs, like “Aaj Mausam Bada Beimaan Hai” from Loafer (1973) or the rain-soaked playfulness of “Ab Ke Sajan Saawan Mein”, from Chupke Chupke (1975) show a performer who could turn a buoyant tune into an expansive emotional mood board. His tenderness revealed itself without any threats to his masculinity. In that sense, Dharmendra adapted himself throughout his 65-year-long career as both a product and creature of the times he lived through.

A glimpse of his comic ease—that flourished so easily in films like Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke—found another manifestation in Pratigya’s (1975) “Main Jat Yamla Pagla Deewana”, where Mohammed Rafi’s spirited vocals turned Dharmendra into a folk hero, all swagger and laughter. The song’s success was such that it spawned a comedy franchise, co-starring his sons Sunny Deol and Bobby Deol, decades later. Then there is “Kisi Shayar Ki Ghazal”, a wistful gem from Dream Girl (1977). Anand Bakshi’s lyrics, combined with Laxmikant–Pyarelal’s composition, give Dharmendra one of his most reflective romantic songs. By 1977, he was a fully-formed icon, but this track reveals a man nostalgic for a softness the industry had begun to deny him.

The late ’70s captured Dharmendra in more melancholic hues. “Hum Bewafa Hargiz Na Thay” from Shalimar (1978) is a heartbroken lament, and Kishore Kumar’s aching voice suits Dharmendra’s restrained performance. Shot during a period when his career was wobbling—caught between leading man stardom and the changing grammar of the industry—the song feels like an elegy for a hero ageing before he was ready for it.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Dharmendra’s image shifted dramatically. As Bombay cinema hardened into action-driven narratives, Dharmendra became their chosen poster boy. Films like Dharam Veer (1977), The Burning Train (1980), and Batwara (1989) foregrounded his brawn over his ability to emote with restraint. The industry had discovered that his physicality could carry entire films, and so it leaned on it until it calcified into typecasting. During this phase, the songs picturised on him morphed as well. Dharmendra’s understated presence of the ’60s and ’70s was subsumed under the weight of his action-hero persona.

By the 1990s and early 2000s, Dharmendra’s presence in mainstream cinema had diminished, though he remained a cultural fixture. He was no longer expected to be the romantic lead or the action hero, but he had become a relic of the past performing himself.

Taken together, Dharmendra’s songs form a parallel biography to his cinematic journey. They chart his shifts, his contradictions, his transformations. They show a performer capable of tenderness, mischief, melancholy, nostalgia, and joy. In the early years, they revealed a gentle, attentive lover. In the action era, they become sparser, more functional, almost in conversation with the industrial demand for masculine spectacle. In the final decades, they return to the emotional reservoirs he had always drawn from. The juxtaposition of his early romantic imagery with his later action persona and the eventual return to vulnerability illustrates how incomplete it is to view Dharmendra only through the lens of physicality.

It was only in late-career works like Life in a… Metro (2007) and Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahaani (2023) that Hindi cinema rediscovered the softness he always possessed. In …Metro, Dharmendra plays an ageing poet rekindling a lost romance. The songs accompanying his storyline, particularly the recurring “In Dino”, conjure the emotional interiority his mid-career films often sidelined. Meanwhile, in Rocky Aur Rani, his character Kanwal stumbles across his memory through music: the smitten gaze he turns toward Shabana Azmi’s Jamini during “Abhi Na Jao Chhod Kar”, the gentle, old-world longing that the film repeatedly channels through classic melodies. While we are yet to see him in Sriram Raghavan’s Ikkis (2025), slated for release on December 26, we will carry an image of these moments. They resurrected the memory of a romantic Dharmendra of decades past; older, yes, but still luminous.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power.

This story appeared as Jat Yamla Pagla Deewana in Outlook’s December 11 issue, Dravida, which captures these tensions that shape the state at this crossroads as it chronicles the past and future of Dravidian politics in the state.