Summary of this article

December 3 marks the 95th birth anniversary of French New Wave auteur Jean-Luc Godard.

Godard was never a cosy consensus figure but a splinter under cinema’s skin.

What makes Godard enduring isn’t just his politics, but the way he understood politics as an artistic grammar.

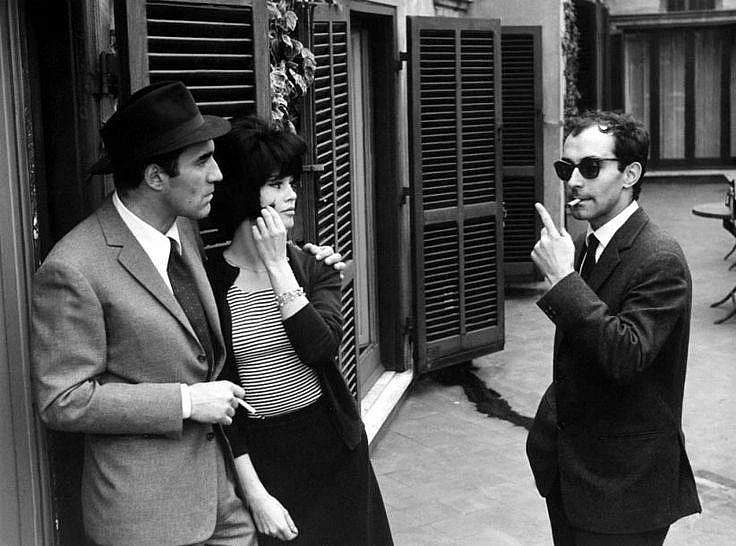

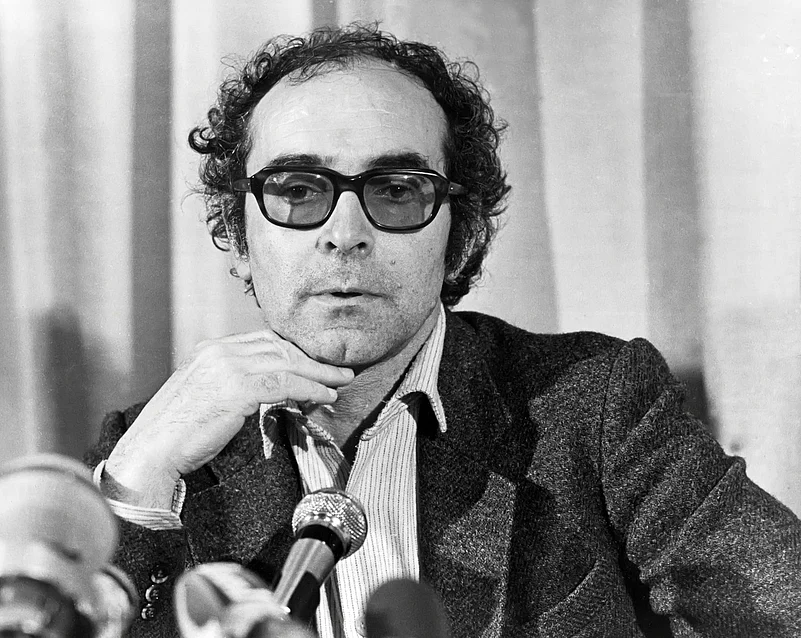

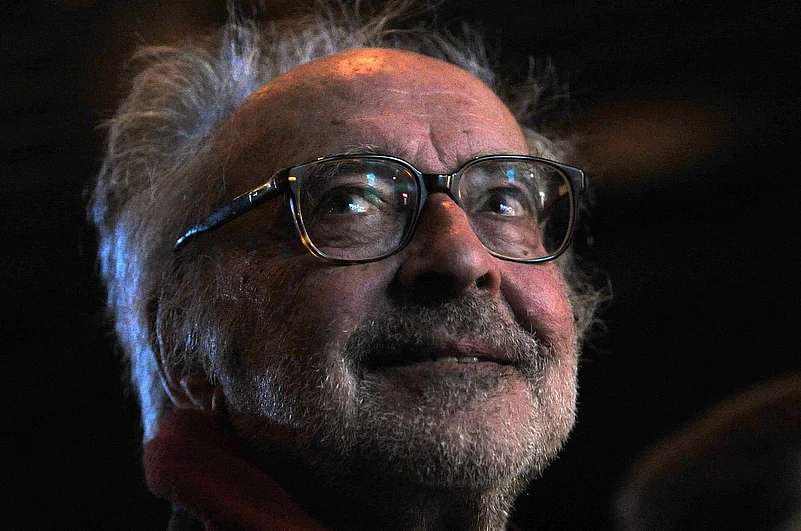

French New Wave pioneer Jean-Luc Godard died just as he lived—like a maverick. On September 13, 2022, at the age of 91, Godard chose to dip out of this realm voluntarily with the aid of an assisted suicide procedure, which is legal in Switzerland where he lived. From the renegade auteur, this felt like one last revolutionary act—a final jump cut to go out of the frame. Even his death had to make a statement.

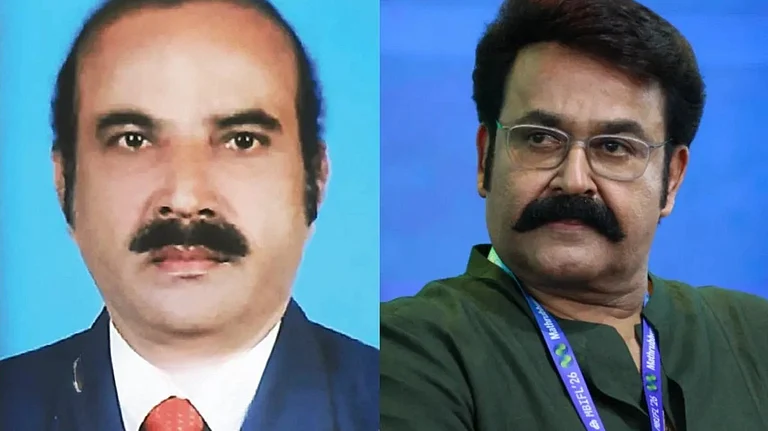

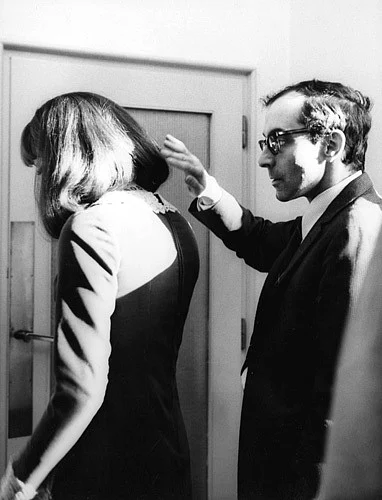

As the world marks his 95th birth anniversary, the temptation is to return to the familiar images: a man with an expression of perpetual impatience, the jaunty insolence of Breathless (1960)—the film that would go on to transform the language of global cinema—and the incandescent heartbreak of Pierrot le Fou (1965). But the Godard that matters now, in this age of algorithmic filmmaking, is the one who saw his art as something inherently political, something that could shake the world out of its complacency and build a better one. His spirit lives on in the filmmakers who continue to go against the grain, creating experimental stories for social media platforms, challenging the attention economy.

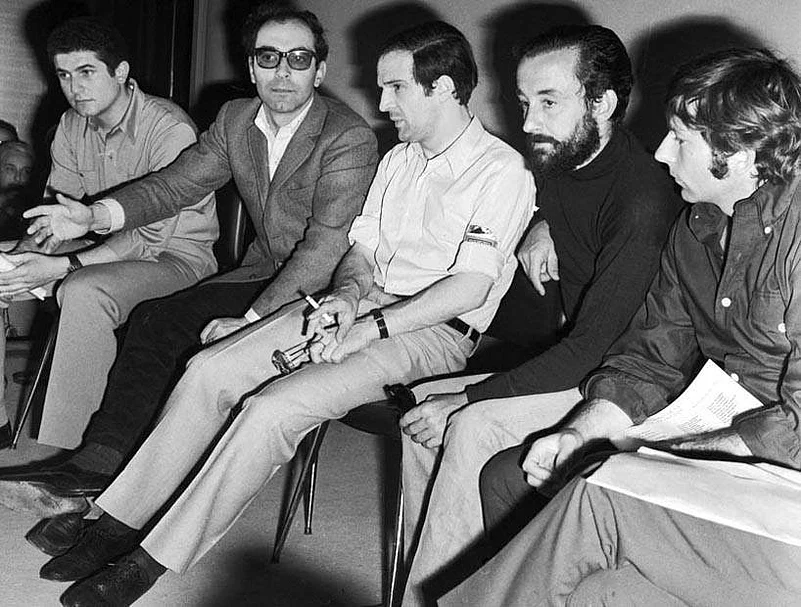

In the years leading up to 1968, Godard had already begun to abandon the flirtatious cinephilia of his early period for something angrier. That decade marked Godard’s political second birth. His so-called Maoist turn was really an anti-imperialist pivot, a furious attempt to prise cinema away from the soft power machinery of the West. But nothing prepared audiences for the moment when a coalition of filmmakers (including Godard and François Truffaut) shut down the Cannes Film Festival as a protest in solidarity with striking workers and students. Cinema, he insisted, could not go on as if the world weren’t on fire. And nothing captures this better than his turn towards Palestine, which brought on accusations of anti-Semitism. He would later clarify that his criticism of Zionist zeal had nothing to do with something as heinous as anti-Semitism.

Across films such as Here and Elsewhere (Ici et Ailleurs, 1976), Godard’s engagement with the Palestinian struggle was markedly ahead of its time. Not in the sense that he was the first filmmaker to want to depict it, but that he scrutinised not just the politics of the region, but the politics of representing it. It is a film that flickers between sympathy, agitation, despair, and shame—an artist horrified at the ease with which he could aestheticise someone else’s suffering.

Of course, reverence for Godard was never universal. For all his militant rhetoric, Godard was hardly immune to the contradictions of a bourgeois radical. He denounced Western imperialism while still moving through its cultural capitals. For every acolyte, there was a filmmaker or critic left nursing a grudge. Truffaut, once a close comrade, famously severed ties after Godard dismissed Day for Night (1973) as bourgeois pap. To this insult, Truffaut returned with a 20-page letter, which contained scathing criticism toward Godard’s political cinema.

In Laura Mulvey’s reading, Godard was a director whose films lay bare the very structures of visual pleasure that feminist film theory would then dismantle. While she critiqued the eroticised framing of and the performative melancholy projected onto his female characters, Mulvey also credited Godard with creating the conditions for feminist spectatorship.

Essentially, Godard was never a cosy consensus figure but a splinter under cinema’s skin—a director who invited love, irritation, and frustration in equal measure.

In an era when geopolitical tragedies are dissected on social media with the breezy detachment of unboxing videos, Godard’s anxiety about representation is almost ancient and practically alien. His question—who has the right to speak for whom—continues to haunt cinema.

What makes Godard so enduring today isn’t just his politics, but the way he understood politics as an artistic grammar. He was, after all, cinema’s great grammarian. He was the man who attempted to pick apart the syntax of images and rearrange the pieces into new sentences. Godard had an almost eerie instinct for locating the fractures of his time and then widening them on screen.

Godard, in his eighties—when he made Goodbye to Language (2014)—was still misbehaving; still searching; still convinced that images could be made to reveal their own deceit. For him, cinema had to be as alive as the moment in which it was made and often, just as unpleasant.

To watch Godard today is to encounter an artist who believed that films should not simply show the world but shake it. And in a cultural moment when art is increasingly treated as a consumable rather than a confrontation, Godard’s ferocity feels even more necessary. To him, the idea that cinema merely be reduced to entertainment and escape was anathema.

He left of his own volition, but his cinema refuses to leave us alone much to the chagrin of film students and cine-neophytes who fail to find rhyme or reason beyond pretension in the great Godard and his lifelong crusade to make every frame an argument—a provocation rather than an escape.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power.