Summary of this article

The “missing woman” is an old crime-fiction trope that has seen a resurgence in recent Hindi cinema and streaming television.

In these mainstream pieces of fiction, the uniformed police officers are the primary, moral agent capable of restoring order.

These texts valorise the police at a moment when empirical data and lived experience suggest a far more troubling reality.

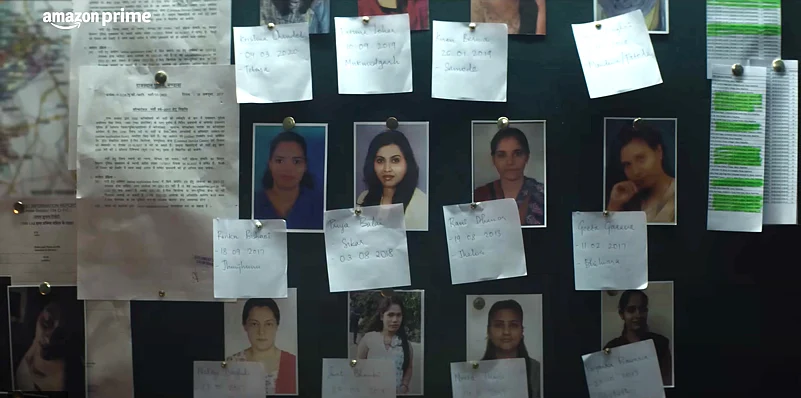

Article 15 (2019), Kathal (2023), Dahaad (2023), Laapataa Ladies (2023), Search: The Naina Murder Case (2025) and Delhi Crime season three (2025) may tell different stories but share two defining motifs. The “missing women” trope operates as the stories’ central catalyst. And in each case, resolution is routed through the figure of the imandaar (honest) police officer, positioned as the moral centre of the story. This officer is invested with the authority to restore order, often through exceptional individual action.

The “missing woman” is an old crime-fiction trope that has seen a resurgence in recent Hindi cinema and streaming television. However, instead of digging deeper, these stories have mostly used the missing women to drive a narrative about good vs. evil and individual heroism vs. systemic collapse. Neither are the young women the focus of these stories nor do they probe the intersections at which these crimes become possible. Everything from poverty to the unlikely culprit of climate change has contributed to the rise of sex trafficking in India. In these mainstream pieces of fiction, you will instead find the uniformed police officers as the primary, moral agent capable of restoring order. In doing so, these texts valorise the police at a moment when empirical data and lived experience suggest a far more troubling reality.

This reassurance is particularly discordant when placed alongside empirical data. According to The Hindu, more than 13.13 lakh girls and women went missing in India between 2019 and 2021, with Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal accounting for the highest numbers. Among the Union Territories, Delhi recorded the highest numbers of missing women and girls in this timeframe.

These figures alone complicate the image of an efficient, responsive police force. They become even more damning when examined through the lens of trafficking, climate vulnerability and caste.

The Myth Of The Police Saviour

Crime fiction has long relied on the fantasy of the police as protectors. They often stand between ordinary citizens and total lawlessness—in the absence of vigilante heroes that is. This fantasy, widely propagated in Western media through the “good cop” versus “bad cop” dichotomy, operates as a form of soft propaganda. It reassures viewers that institutional violence is aberrational rather than structural and that justice is ultimately delivered by the state.

In the Indian context, where policing has historically been intertwined with class, caste and gender hierarchy, political power and communal violence, this fantasy becomes even more ideologically loaded.

In post–George Floyd America, this mythology has at least been partially interrogated in Hollywood. The comedy series Brooklyn Nine-Nine (2013–2021) attempted a self-reflexive turn, especially in its final seasons. Central characters confronted police brutality, racism and homophobia within the force; two protagonists ultimately quit the squad. Such gestures were imperfect and belated, but they signalled an awareness that popular culture could no longer uncritically celebrate law enforcement.

In Hindi cinema, any such comparable self-critique is nearly non-existent. Sandhya Suri’s Santosh (2024), which is still awaiting release in India, is a rare exception to this rule. Not only does Santosh highlight how power gets complicated at the convergence of caste, class and gender, but it also depicts a rare kind of moral ambiguity in its protagonist sans any glamorisation.

In the recent past, mainstream Hindi crime dramas have doubled down on the police procedural as moral reassurance. To their credit, Kathal and Dahaad complicate the saviour trope by casting “double minorities” at their centre. Sanya Malhotra’s Mahima Basor and Sonakshi Sinha’s Anjali Meghwal are not only women but Dalit officers navigating institutions designed to marginalise them. These narratives acknowledge that caste and gender shape both who goes missing and whose cases are deemed worthy of attention. In Dahaad, the victims are overwhelmingly poor, lower-caste women, rendered disposable by both patriarchy and caste hierarchy. Such intersectional framing remains rare in Indian popular fiction, which often treats gender violence as an abstract moral problem rather than a structurally produced one.

However, even these ultimately rely on the police as the locus of agency. Article 15 offers a sharp analysis of caste hierarchies in rural India, but Ayushmann Khurrana’s Ayan Ranjan, who is upper-caste, English-speaking and morally awakened, reinscribes the saviour trope. His “not seeing caste” upbringing is portrayed as realism, yet the story still places transformative power in the hands of a privileged outsider rather than within the community that has been brutalised.

In Delhi Crime season three, vulnerable young women are framed as prey for opportunistic criminals. Structural questions—who is rendered vulnerable, why disappearances cluster around certain regions, classes, gender and castes, and how institutional apathy enables this injustice—remain absent.

The result is a mere morality play that reassures viewers of police competence. The oppressed remain objects of rescue, instead of agents who are capable of driving justice.

Dismantling Through Data

A 2022 reporting by The Fuller Project (in association with The Wire) underscores how disappearances of young women is not merely a criminal issue but a structural one. In the Sundarbans, one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions, thousands of girls go missing each year, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Cyclones, flooding, river erosion, and soil salinisation have decimated traditional livelihoods, pushing many families into precarity, which in turn has led to a rise in trafficking. Climate change, as health economist Barun Kanjilal notes, produces “ripple effects” in which minors on the fringes become most vulnerable.

The Indian state frequently points to a dense architecture of legal and technological interventions to signal commitment to women’s safety. These include post-2012 and 2018 criminal law amendments prescribing harsher penalties, time-bound investigations and trials in rape cases, alongside techno-solutionist measures such as the pan-India emergency helpline (112), Safe City surveillance projects, and a national database of sexual offenders.

However, the persistence of mass disappearances and low conviction rates exposes the limits of our system. Here, the myth of the police saviour collapses entirely. West Bengal’s trafficking conviction rate stands at a staggering 1.9 per cent. Activists and survivors consistently accuse police of failing to register cases properly. Crucially, climate activists argue that trafficking in regions like the Sundarbans cannot be addressed through policing alone. Treating trafficking as a law-and-order problem obscures its roots in climate injustice, migration, as well as economic dispossession.

Crime dramas that isolate trafficking from these socio-economic-environmental contexts reproduce this policy failure at the level of culture. The missing women trope in Indian crime drama could, in theory, foreground structural injustices and institutional complicity. But in practice, these stories repeatedly retreat into the comfort of the simpler police procedurals. Thereby, they risk becoming cultural alibis for a system that continues to fail the most vulnerable.