Raj and DK's The Family Man Season Three released on Amazon Prime on November 21.

The series, starring Manoj Bajpayee in the lead role, reimagines the spy as an ordinary man functioning inside a colossally corrupt and bureaucratic system.

Whereas Bollywood’s spy fantasy is built on hypermasculine bodies and women as decorative proof of the hero’s charisma, The Family Man subverts these tropes.

In The Family Man season three, Srikant Tiwari (Manoj Bajpayee) finally reveals to his son Atharv that he is, in fact, a spy. Atharv, a ballet-dancing, bullied boy, reacts exactly the way any Bollywood-bred teenager would, “Do you have a code name like Tiger, Lion, or Panther?” Srikant retorts that he works for the Intelligence Department, not a circus. It’s a throwaway line, but it effectively skewers Bollywood’s muscular espionage fantasy—currently, sustained by YRF’s spyverse.

The Family Man has always been less about espionage as spectacle and more about the inescapable systems they have to operate within. Here, the spy is an underpaid, overworked, constantly compromising middle-class man who gets stuck in traffic, cannot even get a home loan, and must reconcile with all these failures while tackling the bigger, darker failures that come with working for the state.

Srikant becomes the stand-in for what the creators Raj & DK and writer Suman Kumar (with sharply written dialogues by Suparn Verma) of the show are trying to convey—the world is painted in myriad shades of grey and nothing is as black and white as propaganda would easily have you swallow. In reimagining the spy as an ordinary man, who rolls his eyes at religious bigotry and notions of manhood, the show forces its audience to confront an uncomfortable reality: the people who protect our borders and intercept our crises are merely human. They are not infallible. They are functioning inside a colossally corrupt and bureaucratic system and even when they know it they cannot walk away on a whim.

Our cinema has historically been in love with the spy as national fantasy: the lone ranger, an undying patriot, who single-handedly and willingly risks his life every time to save the country. The Family Man punctures this bubble as it portrays Srikant drowning himself in tears, whiskey, and cigarettes as the burden of isolation bogs him down.

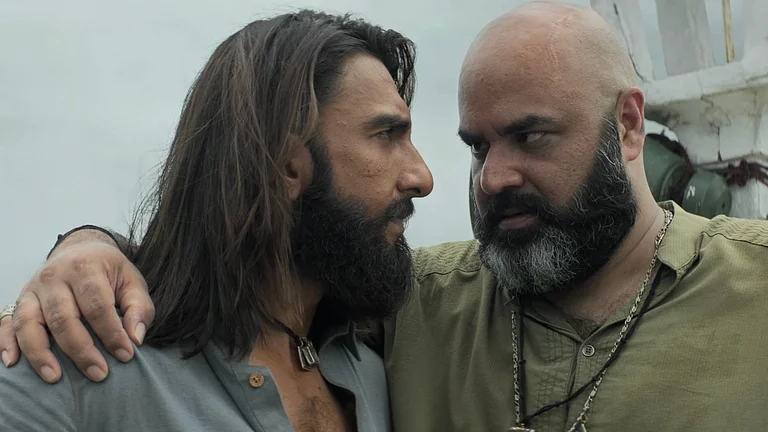

Whereas Bollywood’s spy fantasy is built on hypermasculine bodies and women as decorative proof of the hero’s charisma, The Family Man subverts these tropes. Srikant and his trusted partner JK (Sharib Hashmi) are effective spies because they can meld into the background. The women—Suchi (Priyamani), Zoya (Shreya Dhanwanthary), PM Basu (Seema Biswas), Raji (Samantha Ruth Prabhu)—carry emotional or tactical weight that destabilises the masculine monopoly that commonly foregrounds these stories. None of the women are presented as femme fatales. Even an underdeveloped character like Meera Eston (Nimrat Kaur) is not created to cater to the leery male gaze.

Bajpayee’s Srikant is an anomaly too. He is an everyman operative who is perennially exasperated. He is too broke to afford either suave or sexy as a personality crutch. His team is brilliant but chronically stretched. Watching him scramble between meetings and missions, you realise the show is making a larger institutional critique. The Indian state’s covert machinery isn’t glamorous; it’s underfunded and perpetually dysfunctional. It breeds paranoia from working inside a system that is leaky, heavily politicised, and structurally unreliable.

It’s a world where patriotism isn’t a chest-thumping impulse. Most espionage narratives operate on what theorists call security state exceptionalism—the idea that the state’s violence is inherently justified or righteous because it is protecting the nation. The Family Man quietly questions this by frequently making visible the procedural overreach, surveillance creep, and unconstitutional shortcuts taken by TASC (Threat Analysis and Surveillance Cell).

In season one, when the attack is being orchestrated by rogue agents from Pakistan and ISIS, The Family Man could have easily leaned into anti-Islamic rhetoric and jingoistic sentiments in alignment with the mood of an increasingly divided nation. But the series approaches it with more nuance. It treats Kashmir as a political ecosystem where there is generational impact of militarisation. It criticises the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which gives special powers upon the Indian army in “disturbed” areas. It doesn’t romanticise the insurgents but contextualises them on the basis of historical causality rather than moral absolutism.

This is a show where a Kashmiri Muslim soldier gets to be angry when his loyalty toward the nation is questioned. It does not soften the brutalities that shaped the hardened rebels the state now has to fight. It also does not shy away from pointing out the duality of human nature; both sides have blood on their hands. One person’s freedom fighter often stands branded as another’s terrorist.

Season one portrayed how the 2002 Gujarat riots, the current-day cow lynchings, and the branding of dissent as “anti-national” can give birth to agents of chaos who want to push back. While some become radicalised and pick a gun (the likes of Moosa, Sajid, and Raji in season two), others choose idealism as their weapon of choice (Kareem Bhatt). Much like Kareem, and the likes of Umar Khalid and Gauri Lankesh, even idealistic dissidents cannot find justice in a system adamantly operating with its own set of flaws.

The show doesn’t announce its politics loudly, but reveals the system as it is: multi-layered, disorganised, and more influenced by political mood swings than strategic stability. Here, most of the time evil is not banal or cartoonishly villainous. It is often the product of political and state violence.

The Family Man season three does not have the finesse of the second season, nor season one’s levity. Even the political landscape of Nagaland plays to a familiar tune to the second season of Pataal Lok (2020-2025). But what it lacks in novelty, it makes up for in the simmering dread of a world on the verge of spiralling further.

The multi-billion-dollar military-industrial complex—the main antagonist in season three—is rarely explored in the Indian context with any kind of honesty. But The Family Man lingers on the uncomfortable truth that patriotism, when present at the nexus of politics and late-stage capitalism, is not an unambiguous virtue. Every character thus becomes automatically compromised by the institution they serve. Even when the “good fellas” give in to moments of doubt, they soothe themselves like children that they are doing it all for the greater good. The show knows how to spin the needle of empathy towards critique when portraying its heroes and plays around with the notions of cyclical violence with equal deftness.

Even its form is used as critique. Unlike Bollywood spy productions that fetishise slickness, The Family Man often uses handheld cameras, available light, and location-heavy shooting. As opposed to Bollywood’s choreographed ballet of violence, the series often opts for long takes, imperfect movements, and occasionally off-screen violence. The fight sequences captured through handheld cameras especially feel more lived-in. You can feel the effort and exhaustion. You can hear it in the huffs and puffs.

The makers rely on parallel editing, reinforcing the idea of a chaotic India as a state of perpetual simultaneity, where no one truly has a full picture. Where Bollywood spies get swelling orchestral themes, The Family Man frequently uses diegetic silence to underline the loneliness of covert work.

By grounding espionage in exhaustion rather than spectacle, The Family Man quietly rewrites the genre. By stripping the spy of glamour and placing him squarely inside the machinery he cannot outrun, the show reminds us that national security is a messy, morally compromised grind that devours even its most celebrated heroes whole. It’s a sobering endnote, but The Family Man makes it a damn fun ride.