Iranian actor Homayoun Ershadi succumbed to cancer on November 11.

He was 78 years old and had worked with the likes of Abbas Kiarostami and Dariush Mehrjui.

His prominent films include Taste of Cherry (1997), The Kite Runner (2007), Ágora (2009) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012).

The last couple of days have been strange and surreal. While watching The Perfect Neighbor, my partner and I got a call from his mother that she is going to be hospitalised the next day. As a patient of Chronic Kidney Disease, this has happened before but it felt different this time. She suffered a cardiac arrest minutes after stepping into the hospital and we spent the rest of the day in daze. We live 7000 kilometres away from home and there was little we could do except rely on various relatives for updates on how she is responding to treatment.

Like two people moving sluggishly through unwanted, unwarranted, pre-mourning, we kept each other fed, watched movies and shows to keep our minds off darker thoughts, and then we got to know that Homayoun Ershadi has passed away. At the age of 78, Ershadi succumbed to cancer. He breathed his last on November 11, 2025.

It took us down memory lane. We got talking about Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry (1997), Ershadi’s debut film. We had watched the film sometime during our Film Studies Masters course.

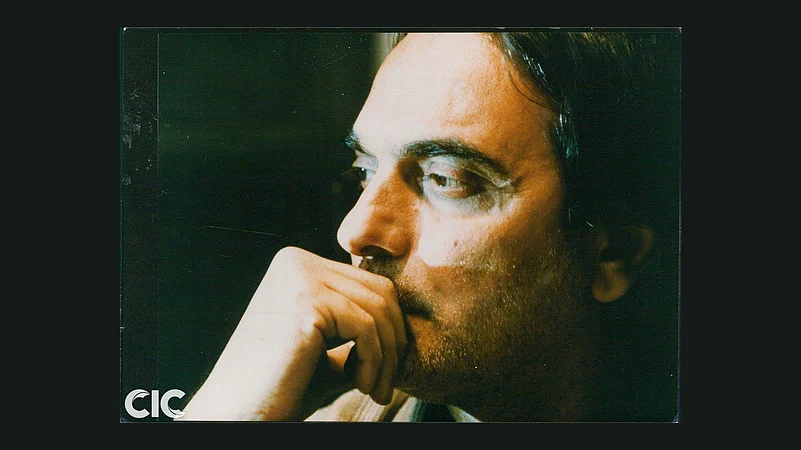

Kiarostami noticed Ershadi by chance, when he was stuck in traffic in Tehran, Iran, and was immediately struck by his face—the quiet sense of dignity and melancholy it carried.

Kiarostami was known for his intuitive casting process: he often chose non-professional actors based on a certain presence rather than performance ability. When he saw Ershadi, he reportedly thought his expression and demeanour perfectly embodied the character of Mr. Badii, a middle-aged man calmly preparing for his own death in Taste of Cherry.

It’s hard to think of another actor whose career began so late and yet felt so complete from the very first performance. Ershadi, an architect by profession, became an emblem of a kind of cinematic interiority that Kiarostami had been refining for years. The camera lingered on his face until it became a landscape of its own.

In Taste of Cherry, Ershadi barely speaks. He drives through the arid hills outside Tehran, offering strangers money to bury him after he kills himself. What remains with the viewer is Ershadi’s stillness, the way his eyes seem to carry the weight of countless unspoken stories.

In the film, it is never revealed why Ershadi’s Badii wanted to take his own life. When my partner first watched it, he really wanted to know Badii’s back story. Now he knows “the why” doesn’t matter. It never did.

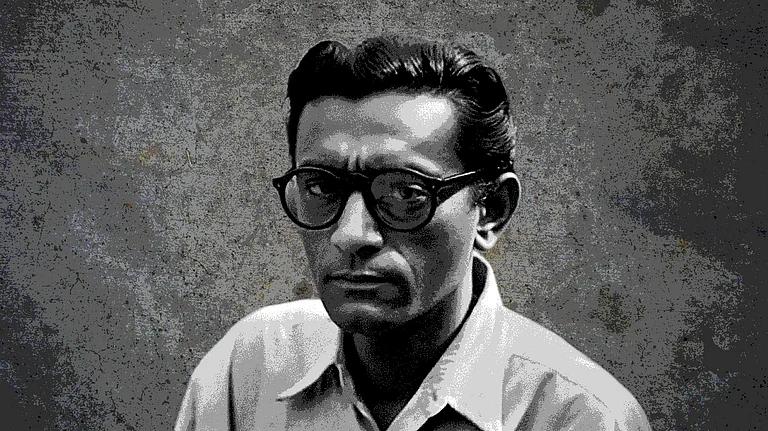

After Taste of Cherry, Ershadi moved from a seismic debut into an international career, appearing in Iranian, European and American productions. His very next performance, in Dariush Mehrjui’s The Pear Tree (Derakht-e Golabi, 1998), remains one of his most acclaimed. In it, he played Mahmoud, a writer looking back on his youth and his first love. The film is often considered one of the high points of 1990s Iranian cinema, and Ershadi’s collaboration with Mehrjui, a pioneer of the Iranian New Wave, cemented his place within that tradition. Mehrjui, a vocal critic of Iranian state censorship, was brutally stabbed to death in 2023.

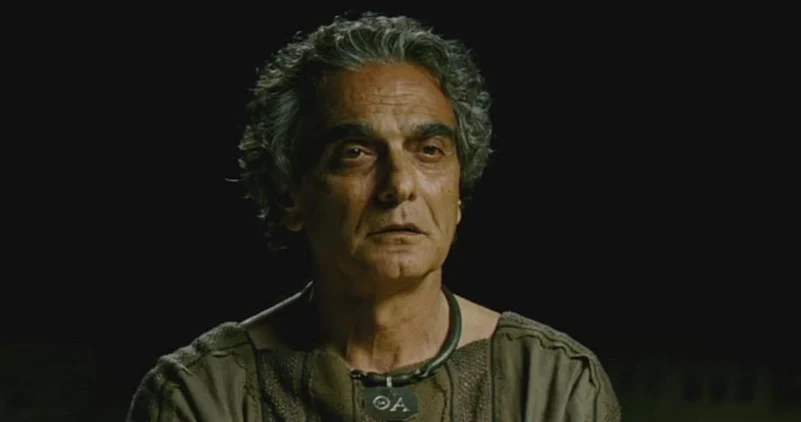

Ershadi’s career extended across continents: he appeared in Marc Forster’s The Kite Runner (2007) as Baba, Alejandro Amenábar’s Ágora (2009) as Aspasius, and Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (2012). These roles confirmed what Kiarostami first noticed: Ershadi’s on-screen presence which became his signature, even when he was working in small or supporting parts. His was an acting oeuvre defined by a rare kind of gravitas.

Seeing Ershadi

In 2018, American author Nicole Krauss wrote a short story called Seeing Ershadi, published in The New Yorker. It’s about two women whose lives are quietly transformed after seeing Ershadi in Taste of Cherry. One has a father dying of cancer. Both are haunted by the same image: Ershadi’s face behind the car window, composed yet filled with feeling, as if he has already made peace with the inevitability of death. For the daughter, he becomes a mirror for what she cannot yet accept—the slow disappearance of her father. For the other woman, he becomes a symbol of serenity, the possibility of dying without resistance.

Watching Ershadi, you understood what Kiarostami meant when he said that cinema was about looking, not showing. Reading Krauss’s story this week, after hearing of Ershadi’s passing, felt like closing a circle. His life had begun with a chance encounter in traffic, and his cinematic afterlife continues in the way we remember his quiet, steady, melancholic gaze.

Taste of Cherry ended ambiguously. We never saw Badii’s death, nor did we find out whether he chose to live the next day. Now I sit here with this ambiguity in my heart as we wait for more news from miles away. I sit here with thoughts of home, Ershadi, and the Taste of Cherry.