Summary of this article

"Fa9la" is a Bahraini rap song from Dhurandhar.

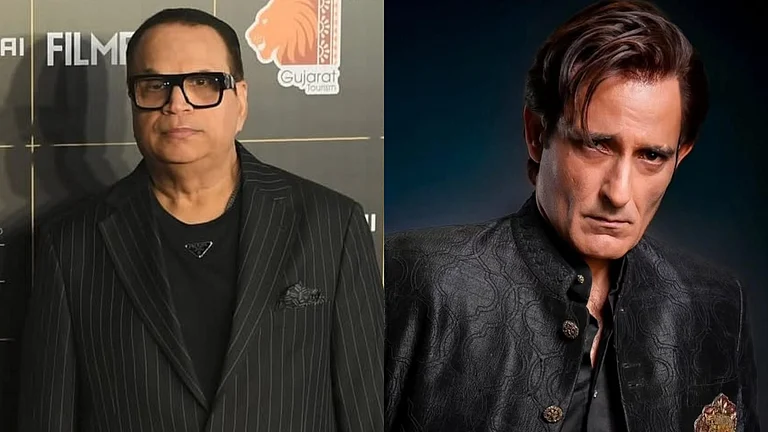

The song introduces the entry of the character Rehman Dakait, played by Akshaye Khanna in the film.

With "Fa9la", Dhurandhar, which was meant to be a saffron-saturated morality tale, has instead become an accidental advertisement for Bahraini rap.

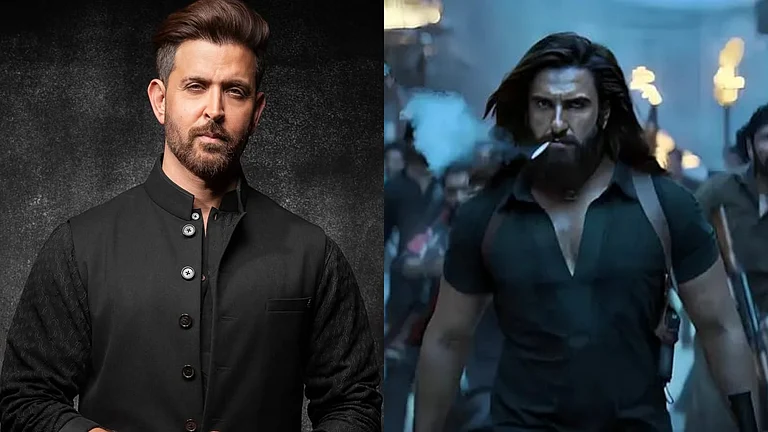

Bollywood has always been adept at creating over the top villains. Sometimes they’re moustache-twirling caricatures; sometimes they’re misunderstood poets; sometimes they’re Ravan-Joker combos. But with Dhurandhar, the propaganda machine seems to have pulled off its most unintended magic trick yet. In trying very, very hard to demonise the Muslim villain, it has accidentally…made him cool. Like, Animal–Bobby Deol Persian-song cool. And the internet cannot resist a cool villain.

What was meant to be a saffron-saturated morality tale has instead become an accidental advertisement for Bahraini rap. The film’s big bad boy Rehman Dakait, played by Akshaye Khanna with his signature “one expression fits all occasions” minimalism, enters to a deliciously slick Arabic track titled “Fa9la” by Flipperachi. Faasla means separation, distance. Ironically, the only thing this song is separating audiences from is the filmmaker’s intended message.

Let’s unpack this slowly, because the layers are funnier than the film.

The propagandists behind Dhurandhar detest Arabic. They want the script gone, the language gone, the people who speak it gone. So naturally, they picked…an Arabic Bahraini track to soundtrack their villain.

Filmmakers: This will show he’s evil. Audience: “Bro, where can I stream this song?” Instagram: “Here are 500 reels thirsting over the villain.”

Bollywood has pushed the Hindi film hero so far away from adab, from qawwali, from the sensuousness of Urdu and Arabic rhythms, that the villain now gets the better playlist. The hero gets patriotic EDM. The villain gets Bahraini flow, Arab beats, and the confidence of a man who knows he is more memeable.

Audiences, being culturally starved by nationalist sanitisation, gravitate to the cool guy. If the hero can’t flirt, can’t smoke, can’t drink, can’t listen to “foreign” music, can’t cheat unless it’s justified by ‘Papa trauma’ and can’t appear morally messy, then the villain becomes the only character allowed any cinematic pleasure.

Ranvijay in Animal (2023) cheated on his wife, but it had to be wrapped in the justification of filial obsession. Meanwhile Abrar and Aziz were allowed to be unrepentant womanisers. Because heroes can't just cheat, there must be a tragic backstory, a ritual cleansing and a national interest explanation. But the Muslim villain? He gets to enjoy life without footnotes.

The very discourse meant to warn us, “This is Islamophobia”, has unexpectedly found fans. Yes, the caricatures are there. Yes, the film has a clear ideological thrust. And yet, everywhere online, one sees the Animal-effect repeating itself: reels, edits, fans 'stanning' the highly caricatured Muslim villain—the forbidden fruit principle.

Tony Soprano. The Joker. SRK in Darr (1993). The aforementioned Abrar. You can demonise them, but you cannot make them uncool. Bollywood’s latest attempt at moral engineering seems to have forgotten one rule of pop culture: Villains are almost always cooler than the heroes. Especially when you give them better music.

Let us pause to appreciate the cosmic comedy of “Fa9la” (yes, spelt with a digit, like all Gulf rap). A Bahraini Arabic song is now viral across India. A language the right-wing ecosystem fears, mocks, and occasionally fantasises about banning is now blasting through gym speakers in Noida. The Hindutva project may have accidentally become an ad agency for the Arab world.

Give it a month, maybe less, and you will inevitably see a wedding video from Lahore, Karachi or Islamabad—the groom’s cousins doing a choreographed entry to “Fa9la” from Dhurandhar; Pakistani kids dancing to the soundtrack of an Indian anti-Pakistan, Islamophobic film. History shall repeat itself: first as tragedy, then as wedding choreography.

Audiences in India and Pakistan do not even understand Arabic or Persian. But post-Animal and now Dhurandhar, they know one thing; these languages sound cool. They feel rebellious. They feel luxurious. They feel like everything the sanitised hero is no longer allowed to be.

When you strip the “hero” of all cultural richness, no poeticism, no sensuality, no linguistic range, and hand all the masala, swagger, pleasure and rhythm to the villain, the audience has no choice. They will follow the pleasure. They will follow the music. They will follow the character who looks like he’s allowed to live. The unintended by-product of propaganda filmmaking is that sometimes, it becomes propaganda for the wrong side.

Bollywood keeps trying to tell us: “Look, he’s the villain because he listens to Arabic rap!” But the viewer replies: “Okay, but…where can I download this track?”

Dhurandhar wanted to show us the danger of the Muslim antagonist. Instead, it has given him a fanbase. And an Arabic banger of a theme song.

The film tried to create fear. The internet created thirst.