Cinematic representations of illnesses, especially in Bollywood, often romanticise medical conditions for pathos.

In most of these films, characters are written not as patients but as props.

Cinema has played a role in raising awareness about such illnesses. But raising awareness is not the same as fostering understanding.

Cinema has always been drawn to human frailty. Tuberculosis once gave heroines a beautiful cough and a poetic death. Later, cancer entered the screenplay as the ultimate tragic trump card—hair loss, chemotherapy montages, the final farewell. When that lost its freshness, filmmakers reached for another devastating illness—dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. It comes preloaded with everything cinema thrives on. Memory, identity, love, loss! What could be more heart-breaking than watching someone forget who you are?

But as with all cinematic obsessions, there is a catch. In the rush to harness Alzheimer’s for guaranteed pathos, Bollywood often reduces the condition to a narrative convenience. Characters are written not as patients but as props—obstacles in a romance, metaphors for darkness, tools to wring out tears. And while this may deliver a high-voltage climax, it rarely does justice to the lived reality of dementia.

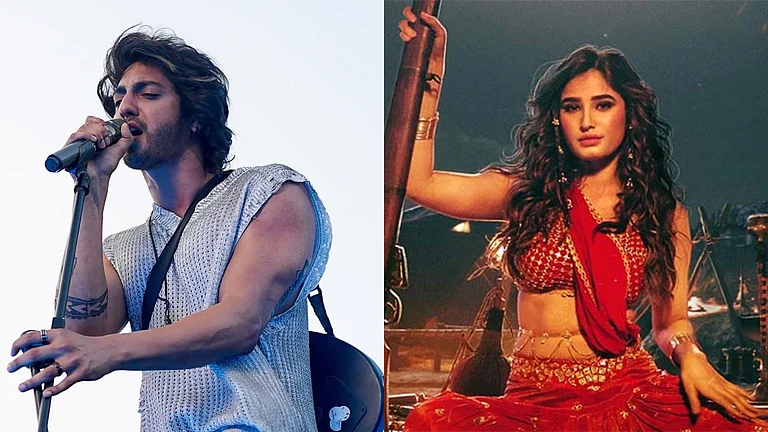

In Mohit Suri’s Saiyaara (2025), a tragic romance built around early onset Alzheimer’s, the heroine, played by a radiant Aneet Padda, is barely in her twenties. Medically, early onset Alzheimer’s refers to the disease diagnosed inpatients younger than 65, often occurring in the 40s and 50s. Any younger than that is extremely rare, with only a handful of cases reported worldwide. Yet in cinema, it has become strangely prolific—a perfect narrative device for heightening love stories with the ticking clock of memory loss.

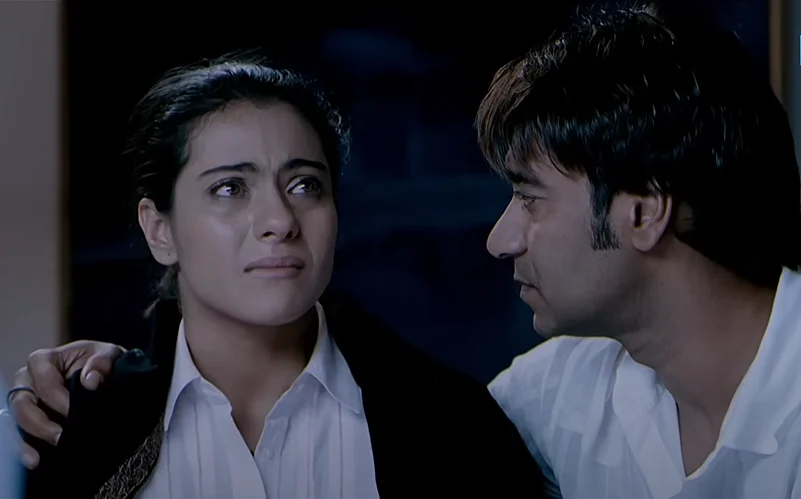

Saiyaara is not the first. Back in 2008, U Me Aur Hum cast Kajol as a young woman whose early onset Alzheimer’s endangers her marriage. Both films deploy the same “race against time” structure. Lovers must marry, reconcile, or cling to each other before the disease erases their bond.

The illness becomes, essentially, a new villain replacing the conservative parents, the caste system, or the scheming in-laws of earlier Bollywood melodrama. For today’s multiplex audience—urban, liberal, financially comfortable—those old conflicts no longer carry the same weight. Alzheimer’s steps in as the new impossible obstacle.

But here is the problem. In these films, the patient’s inner life is barely explored. What we get instead is the caregiver’s anguish. We watch the lover suffer as he “loses” his partner, but the camera rarely lingers on what it feels like for the woman herself—the disorientation, the flashes of clarity, the quiet humiliations. The story is told not with her but around her.

Black (2005) takes a different track. The director, Sanjay Leela Bhansali turns dementia into an operatic vision of disability and darkness. For Amitabh Bachchan’s teacher figure, Alzheimer’s becomes the second darkness, a metaphor for the erasure of self. Bhansali, the aesthete, uses the disease as symbol rather than condition. It is grand, moving and visually striking. But hardly accurate! The clinical realities of Alzheimer’s—the wandering, paranoia, incontinence, the slow erosion of executive function—are absent. Instead, we get a metaphysical loss of identity.

This is not to say metaphor has no place in cinema. But when metaphor replaces detail, the result is a glossy, almost glamorous suffering—attractive in its theatricality, divorced from the daily indignities of the illness.

In Sudheesh Sankar’s Tamil film Maareesan (2025), Alzheimer’s is reduced to a narrative scapegoat. Vadivelu’s character Velan has the disease when he first meets the thief played by Fahadh Faasil. But the “twist” reveals Velan was faking it all along. Alzheimer’s is used not as a condition but as a cheap gimmick, a bait-and-switch for shock value. Worse, Velan turns out to be a cheat and a killer, reinforcing the damaging stereotype that people associated with dementia are dangerous. By the time the film reveals that it is actually Velan’s wife who had Alzheimer’s, the damage is done. A serious neurodegenerative disorder has been reduced to a plot device, stripped of sensitivity or insight.

Among films from across the world, Still Alice (2014) gave us a different kind of protagonist. Julianne Moore’s linguistics professor narrates her own unravelling. We see her confusion, her terror, her attempts at control. The focus is not on the family’s grief but on her subjective experience. The result is a film that generates empathy not through manipulation, but through intimacy.

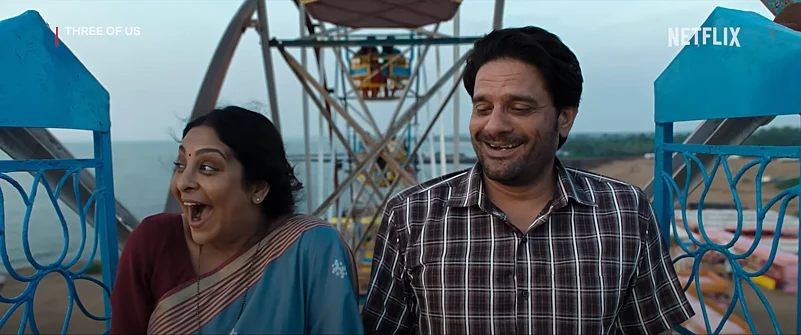

Sometimes cinema does get it right. Avinash Arun’s Three of Us (2023) is a film that doesn't lean into melodrama or simplify Alzheimer’s into a tragic obstacle. It treats Shailaja’s (Shefali Shah) experience as something messy—she sometimes struggles, loses recent memories, feels guilt and longing, and is aware of her own fading agency.

Unlike Saiyaara or U Me Aur Hum, Three of Us doesn’t turn dementia into a “villain” to be defeated by love. Instead, the illness becomes part of a reflective journey, one that involves loss, yes, but also acceptance, nostalgia, and grief treated with tenderness.

Pushan Kripalani’s Goldfish (2023) is another honest Indian film about dementia. Deepti Naval plays a mother with the condition and Kalki Koechlin, her estranged daughter. What makes Goldfish remarkable is not only Naval’s sensitive portrayal, but the community that surrounds her. The film situates dementia not as a private tragedy locked in a nuclear household, but as a collective reality. The neighbours—fellow immigrants in London’s South Asian enclave—step in with their awkward kindness. It is messy, sometimes comic, often frustrating. In other words, it is real.

Dr Harish Shetty—a Mumbai-based psychiatrist who deals with patients suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s—insists that community is vital in dementia care. Patients fare better when there are many people to support them, not just one overburdened spouse. In films like U Me Aur Hum or Saiyaara, the patient is left with a single “super loving” partner—an idealised but isolating scenario. Goldfish breaks that pattern, showing that illness need not always be borne by individuals alone, but can also be dealt by networks of care.

In real life, dementia is rarely the solitary, romanticised journey cinema makes it out to be. Families fracture under its weight. Children fight bitterly over wills and caregiving duties. Spouses seethe with resentment at the unrelenting demands of looking after a patient. These are the everyday realities Dr Shetty encounters in his practice. And yet, in Saiyaara, the patient’s parents conveniently step aside, abandoning their daughter to a near stranger, who spirits her away to an isolated house she is unfamiliar with. It is the very opposite of what professionals recommend. Dementia care, Dr Shetty stresses, thrives on familiar spaces and networks of support, not the fantasy of one self-sacrificing individual in splendid isolation.

In Saiyaara itself, there is one detail that rings medically true. Padda’s character recalls her past lover with far more clarity than her present partner. Neurologists confirm this is typical: in dementia, the most recent memories erode first, while older ones often remain intact for much longer. It’s a rare moment of accuracy in a film otherwise shaped by fantasy.

But then comes the silence around another clinical truth—sexuality. Dr Shetty points out that sexual desire is often the first faculty to fade in dementia, and with it, the ability to give meaningful consent—which makes Bollywood’s recurring trope of “tragic love stories” culminating in marriage deeply problematic. When Padda’s character in Saiyaara marries her suitor despite already showing signs of decline, the film frames it as a grand victory of love. Yet medically and ethically, this raises red flags. Can someone in the throes of cognitive impairment truly consent to lifelong partnership? By romanticising such unions, cinema risks normalising what, in reality, is a consent gap.

If Bollywood is still learning how to handle dementia, theatre sometimes does better. In The Father, Florian Zeller’s devastating play staged in India with Naseeruddin Shah, audiences experienced the disorientation of dementia from within. Sets shifted, characters blurred, timelines dissolved, mirroring the protagonist’s fractured mind. Shah’s performance, Dr Shetty observed, was deeply studied, attentive to detail. Unlike the glossy shorthand of film, the stage offered fidelity to psychological truth.

To be fair, cinema has played a role in raising awareness. Just as TB in old films, or cancer later, introduced audiences to illnesses they may not have otherwise discussed, dementia on screen has spotlighted the condition in public conversation. That is no small achievement. But raising awareness is not the same as fostering understanding.

The danger is that Alzheimer’s becomes shorthand for tragedy, stripped of complexity. The condition is framed as inevitable decline, with little exploration of the many years patients may live with dignity, humour, and agency. We do not see families adapting, communities stepping in, care structures evolving. We see only the tearful goodbye.

Mainstream cinema loves a glossy overview. It loves glamour even in suffering. But dementia is not glamorous. It is chaotic, unpredictable, demanding. If filmmakers truly want to tell these stories, they must move beyond melodrama and consult the experts—neurologists, psychiatrists, caregivers, who know what the illness entails. They must give patients their subjectivity back, rather than making them satellites orbiting the caregiver’s pain.

Alzheimer’s is not just a script device to replace outdated tropes of caste opposition or parental disapproval. It is a lived condition, affecting millions of families. To reduce it to a cinematic obstacle is not only lazy storytelling; it is a disservice to those navigating it in real life.

If filmmakers choose empathy over narrative crutches, they may illuminate not just what it means to forget, but what it means to care. After all, as Elizabeth Bishop reminds us, the art of losing isn't hard to master.

Samina Motlekar is a screenwriter and former advertising film producer based in Bombay.