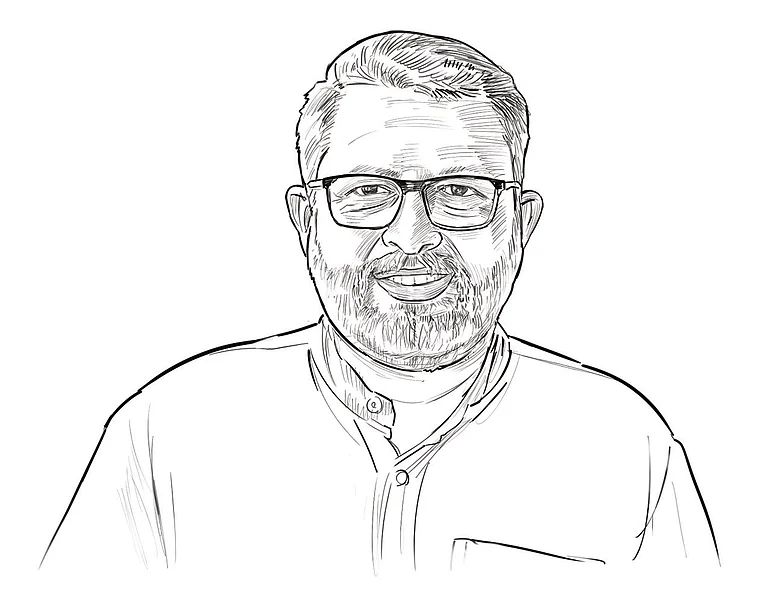

Angammal (2024) directed by Vipin Radhakrishnan, initially premiered during MAMI film festival in 2024 but is set to release theatrically in October this year.

The film has attained several accolades like “Best film”, “Best indie film” and “Best performance female” categories in New York and Melbourne.

In conversation with Radhakrishnan, the following interview unravels his craft and its inner workings.

Few films place their faith in a strong female lead, but that faint thread of hope finds a pulse in Angammal (2024). It is a work with heart, with fierce ambition, and the courage to confront what lingers in those who have refused to evolve with time. The logline of the film itself commands attention: a mother who resists wearing a blouse beneath her sari, urged otherwise by her doctor son, who clings to an image he must uphold before his future in-laws. The film sets out to explore far more than bodily autonomy. It reaches into the fragile textures that hold families together, where affection and resentment often coexist in unsettling harmony.

Angammal recently claimed Best Film at the New York Indian Film Festival, while also securing Best Actor (Female) and Best Indie Film at the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne. Its journey began with a premiere at the prestigious MAMI Film Festival, Mumbai, in 2024, where it was first celebrated for its sensitive approach and rare sensibility. In the process, Angammal has emerged as an important voice, a reminder that independent cinema can still anchor itself in tenderness, while leaving an indelible mark on the larger landscape. Set in the Padmaneri village, the landscape itself becomes paper, while its characters become the ink that stains it. The screenplay, adapted from a short story by Perumal Murugan, is carried into cinema by Vipin Radhakrishnan, who lends it his own sensibility, rhythm, and narrative voice. His Angammal is both homage and assertion, borrowing the bones of Murugan’s text while building a body entirely his own.

In conversation with Sakshi Salil Chavan for Outlook India, Vipin Radhakrishnan reflects on the delicate task of transforming a short story into a full-length screenplay, his view of the terrain contemporary filmmaking must now navigate, and the distribution struggles that still weigh heavily upon indie cinema.

Edited excerpts:

You initially came from an architecture background, before making a switch to filmmaking. What events and decisions in your path led to your directorial debut Ave Maria (2018)?

Like many Indian households, mine carried the expectation of medicine or engineering. I chose architecture, thinking it carried at least a fraction of creative license. But my real passion had always been tethered to cinema. As a teenager, I often bunked classes to slip into dark halls with friends, chasing that illicit thrill of watching films on a big screen. At that age, I didn’t yet have the courage to tell my parents that cinema, not architecture, was my chosen path. In Trivandrum, my exposure widened. Seniors would attend IFFK and I found myself swept into that world. We watched indie festival films, world cinema, and timeless classics, often pirated and passed around the hostel. That community of discovery cemented a belief in me: this was where I truly belonged. Architecture, however, was not wasted time. It remains the oldest and grandest of art forms, and it trained my eye for space, balance, and composition. Those lessons became the bedrock of my filmmaking, shaping the way I build shots and design visual rhythm. I assisted in films, co-wrote and then eventually directed my first, Ave Maria (2018). The journey has been quite fruitful as I’ve made my second, Angammal (2024), and am working on upcoming projects. Today, my parents have made peace with this choice. They see the momentum my films are finding, even if in their hearts, they still hope I will deliver a blockbuster one day.

You’ve mentioned that the screenplay was deeply influenced by your stay in Padmaneri village. Were there any particular incidents, individuals, or details from that experience that directly shaped the film?

The concept of the “Uchchimala” winds originated in Padmaneri village. It was never written into the script or the short story, but simply living there transported me into another time. We stayed for three months, meeting people whose presence seeped into the screenplay. Their gestures, their stories, and even their silences shaped the rhythm of our characters. I remember the women dressed in saris without blouses—their appearance reaffirmed Angammal’s character both in texture and in spirit. Padmaneri itself carried a strange duality. A corner shop ran UPI payments, yet the streets, the houses, the lives unfolding there still belonged to the 90s. That tension between the old and the new gave the film its essence. The wide shots of fields and mountains were not aesthetic choices but lived realities, capturing a population still tethered to nature.

One summer evening, a hill in the distance caught fire. The blaze spread across the horizon and in that moment, the landscape itself became otherworldly. That vision of a mountain burning, real yet fleeting, gave me the language to push the story toward magical realism. It felt less like invention and more like a translation of what was already alive around us.

In Angammal, you didn’t simply translate Perumal Murugan’s short story to screen—you layered it with your own, at times even conflicting, narrative voice. What creative challenges did you face in balancing fidelity to the source material with your own interpretation, and how did you navigate them?

From the very outset, I was clear that I did not want the film to slip into a preachy register. Stories about autonomy often risk being reduced to “issue cinema,” but Angammal attempts to resist that bracket and instead grow into a reflection on the entanglements of self, family, society, and nature. The short story we began with had no names, no Uchchimala winds, not even the ending that eventually shaped the film. Those choices emerged from our attempt to root the narrative in the geography we were working within. The village itself carried a voice, offering characters and conflicts that could never have been conceived in isolation. Every figure in the film was given their own frailties, burdens, and flashes of redemption.

Take Geetha Kailasam’s Angammal, for instance—she moves like the Uchchimala winds, elemental and untamed, and yet the film asks you to see her in her greyness, not as an archetype but as a force capable of stirring empathy. For me, true acceptance lies in seeing someone in their rawest form and still recognising it as love. If I imagine myself in Pavalam’s (Saran Shakthi) position, I too would have wrestled with the dissonance between a rapidly modernising India of the 90s and a mother still rooted in her soil. I wanted to create a world for these characters without judgement, where each of them could stand with their contradictions intact—received not through verdicts but through understanding.

After massive wins in New York and Melbourne, Angammal will hopefully soon see a pan-India release. As a filmmaker, marketing doesn’t come as naturally as storytelling does and distribution for indie films is quite a feat to accomplish. What kind of roadblocks have you encountered while working towards taking the film to a larger audience?

Fortunately, our film continues to reach a certain segment of the commercial cinema audience. For that I owe a great deal to director Ram, a towering name in the South film industry. He encouraged us to make the film we truly wanted to, so long as we had something purposeful to express, and connected us with production houses in Tamil Nadu that responded to our vision. We were fortunate too, that the Malayalam industry welcomed the sensibilities we wanted to experiment with. Now we are seeking partners who can help us expand the film’s reach across India.

Yet, the most persistent obstacle in distribution remains the question of who the star is. Even on OTT platforms, the fate of a film is pushed further into the cycle depending on the names attached to it, rather than the merit of its story. Angammal rests on the shoulders of Geetha, our female lead. She isn’t a superstar in the conventional sense, though she has played mothers to several of them. As a solo performer, this was her first outing and that freshness drove her to deliver a remarkable performance. But in marketing and distribution, conviction and strategy matter as much as capital. A film like Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine As Light (2024) stands as a rare instance, where vision and strategy transformed the reach of independent cinema. With the backing of Rana Daggubati’s Spirit Media, its release ensured not only international acclaim but also wide visibility within India.

Seasoned professionals in the distribution business should not surrender to the absence of a star. The challenge is to think differently, to market the story itself in a way that compels audiences into theatres. Indie cinema, even when allotted screens, depends heavily on word of mouth or sheer luck to draw viewers in. What’s missing is a structural process—an inventive, thoughtful approach to marketing that can frame strong films without superstars for the audiences who would embrace them. That is the area I am interested in exploring. The risk is not in indie cinema, but in the unwillingness of stakeholders to make that extra effort. Even festival films that gather international acclaim face the same issue when they come home.

You’ve spoken about not wanting Angammal to remain within the “festival film” bracket, but instead to connect with a wider pan-India audience. How do you see audiences from different contexts engaging with it?

The measure of a film that transcends boundaries of geography, culture or even personal circumstance lies in its fidelity to character. The story I have pursued is born from the women who shaped me—the mothers and grandmothers who left behind indelible imprints on the generations after them. In cinema, matriarchs are rare; yet, within Indian homes they have always been the quiet force—single mothers, widows, sisters and wives carrying entire worlds on their shoulders. Their forms shift, their vocabularies change, yet their strength persists, asserting itself in everyday gestures of survival and identity.

India itself carries this history in fabric. Before colonial intrusion, saris were worn blouse-less, only later refashioned by western influence. Even today, many women embrace that older freedom, a reminder that tradition often lies in what is seen as forgotten. Angammal grows out of that space: a film dedicated to protecting the right to live, express and exist without dilution. It holds close the idea that one is lovable precisely as they are. For those who have watched their mothers and grandmothers age gracefully in the garments of their choice, the film will feel both familiar and moving.

Yet Angammal resists the solemn weight it could have carried as a niche festival film. Instead, I have threaded its narrative with humour, pauses of relief, moments of sharp tension and spaces for quiet reflection. It is a complete experience—one that allows different audiences to enter at different points, without dictating how they must feel. My only hope is that it touches those open to it, that it reaches the hearts willing to listen.

In India, commercial film budgets often revolve around star power, with most of the resources channelled toward the star while the crew is left to compromise. This disparity not only reduces fair pay but also weakens production value, often at the cost of storytelling. What, in your view, needs to shift for audiences in India to start choosing better films?

Filmmaking is and has always been a labour of love, even when that devotion remains invisible to the viewer. What ultimately appears on screen is born of a collective faith—a group of people who believed in a story enough to shape it with their craft and, at times, their own hard-earned money. Once, making a film was painstaking, often limited by the weight of analog tools. I learnt from senior sound mixing engineer T. Krishnanunni that to create something as simple as an echo, one had to resort to practical ingenuity like recording inside a cave. Today, with digital ease, the same can be achieved by pressing a button, and entire films can now be shot on a phone. This shift has been witnessed by technicians who have seen both eras, carrying with them a layered wisdom. I hold my team in the highest regard. My editor, Pradeep Shankar—who also worked on my debut Ave Maria and several Malayalam films—lent his sharp eye to this project. My DOP Anjoy Samuel; and Firoz Rahim, carried the film forward as producers along with Shamsudeen Khalid and Anu Abraham (who are based in Qatar) purely out of their sheer belief in the narrative. This was also the first time that celebrated Malayalam singer Mohammed Maqbool Mansoor composed music, working in close sync with sound designer Lenin Valapad. Each person contributed not only skill but faith, and it is that faith which breathes life into cinema. Change can only be real when such collaborators receive their due, not just through monetary respect, but through visibility and the recognition of audiences who affirm their work.

Any film that comes into being eventually has to be sold, and in most cases, familiar faces make that easier. Too often, scripts are designed with a star in mind, their preferences shaping the very fabric of the narrative, which flattens the possibilities of storytelling. What we don’t see enough of is the kind of directorial command that exists in certain industries, like South Indian film circuits or even Hollywood, where the filmmaker carries the weight of bankability on their own name. There, the star becomes secondary because the director is the true draw. That’s the shift we need across India, to move towards films that feel worth stepping into a theatre for, where the director and the story eclipse the machinery of stardom. Though some may disagree, it feels like the only way forward.

As a filmmaker and an artist, are there certain themes or questions you feel destined to keep returning to, or do you allow each film to chart its own path? On that note, what’s next for you?

This is only my second film, and I still see myself as fairly new in the directorial chair. Each story, I believe, carries its own pulse, and I allow it to reveal itself in whichever thematic form it wishes to take. Perhaps with time and more films behind me, I will set out to deliberately explore specific themes or questions. For now, even bringing a film into being feels like a remarkable feat in itself. With Angammal, I had the privilege of working alongside seasoned actors, an incredibly skilled crew, and a cast that brought extraordinary texture to the narrative.

When I first entered filmmaking, I dreamed of collaborating with big names, and in truth, I still do. Not because of their fame, but because of their sheer craft as performers. That remains an aspiration: to consistently surround my films with the finest talent, regardless of whether the project is a guaranteed box office success. Results vary for countless reasons, but I believe wholeheartedly that an investment in excellence will always bear fruit on screen.

Commercial cinema too, when made thoughtfully and sensitively, can resonate in striking ways. People often warn against chasing both mass and independent sensibilities, but I’ve never believed in that divide. A film like Dangal (2016) spoke across borders, finding its most devoted audience in China, while addressing women’s empowerment, patriarchy, sport, national identity, and the delicate bond between a father and a daughter. My instinct is always to serve the story in the most honest way possible. That remains my compass. At present, I am working on an upcoming Malayalam project, a more commercial film. I want my work to live in spaces where the largest audiences gather, and yet I want to bring to those spaces the kind of storytelling that carries weight, soul, and craft.