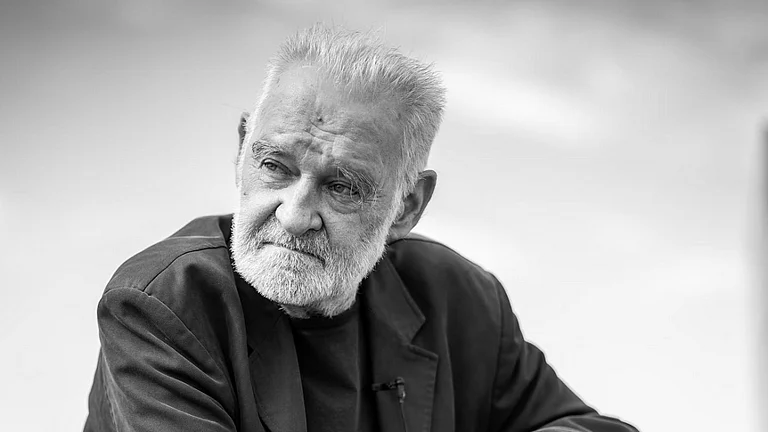

Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr died on January 6, 2026 at the age of 70.

He was an artist who practiced the transformative capacity of cinema as an instrument of defiance and creation.

Tarr leaves behind not merely a body of films but a way of thinking cinematically about ‘Being’ as something that unfolds, erodes, and persists under time’s pressure.

“For each time, and each time singularly, each time irreplaceably, each time infinitely, death is nothing less than an end of the world.”

-Jacques Derrida, 2005

To mourn is never just to register an absence, rather to confront the disappearance of a singular world, even when the works they made, the thoughts they set in motion and the forms they shaped continue to live among us. To mourn Béla Tarr, then, is not to grieve a life, but to harbour that something that is greater than the person; something outside of us, within us. What remain are the traces of a way of seeing, a way of thinking, a way of time, a way of cinema.

“I have my own manias,” Tarr said in a 2023 interview with Scott Foundas, “like seeing the face as a landscape…” Indeed, Tarr’s cinema was never actually about faces as psychology, nor landscapes as backdrop. Faces were terrains eroded by time; landscapes were moral climates; both were subject to duration, exhaustion and an unrelenting measure of history. With his death at 70, cinema loses a director, indeed, but also one of its last uncompromising metaphysicians—an artist for whom film was not storytelling, but an ethical and ontological wager; an artist who practiced the transformative capacity of cinema as an instrument of defiance and creation.

Across decades, Tarr’s work became an increasingly stripped and severe, yet operatic and arresting cinema. Each film removed another layer of narrative reassurance, another illusion of progress, until only bodies, time, and “something else” remained. This was not minimalism as taste but necessity. When he announced The Turin Horse (2011) as his last film—a decision not born out of exhaustion, but of philosophical completeness of sorts—it seemed he had said what needed saying. The rest was silence, archive, pedagogy, and increasingly, installation art; cinema's dissolution into phenomenology.

Long before “Slow Cinema” became a curatorial disposition, Tarr had already committed himself to duration as a political and aesthetic position. Across Sátántangó (1994), Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), The Man from London (2007) or The Turin Horse, Tarr shaped a cinema of attrition and accumulation. His long takes were not intended to redeem despair or aestheticise ruin, but to stay with details that will reveal themselves through and in time. He deliberately evacuated narrative in favour of attention, replacing action with repetition, allegory with atmosphere, meaning with presence(ing). Whether a whale arrives in a truck or a father and daughter persist beside a horse that will no longer move, the end does not arrive with announcement or rupture, but seeps in gradually, through malfunction, decomposition and the cumulative failure of things.

His black and white world is steeped in, yet beyond the threshold of stylistic mannerisms—it is a demand placed upon us, the viewers, insisting on a form of attention that refuses to be calibrated to reward. When/ever he refused to cut, cinema reached what Rancière identified as its most radical capacity—not to represent time or symbolise waiting, but to enact duration itself. Yet, Tarr’s cinema, though severe, was never cruel. His characters were never saved or transformed; rather, they were to endure. Their dignity rested not in progress but persistence, in the stubborn continuation of life when history had exhausted all its promises. No moral humanism but existential fidelity: a commitment to remaining, even as nothing happens, so many times over, and ever so slowly.

What Tarr leaves behind, then, is not merely a body of films but a method, a way of thinking cinematically about ‘Being’ as something that unfolds, erodes, and persists under time’s pressure. In a world colonised by images, dictated by acceleration and distraction, he insisted that cinema’s task is not to entertain, console, or resolve, but to arrest, to detain us within the image, and to make felt the weight of existence that cannot be skipped, summarised, or escaped and to be left with or leave with something magnificent, something beautiful, something profound, something unnameable.

Politically uncompromising, Tarr scorned Hungarian state power, the complacency of facile left-wing rhetoric and the seductions of nationalism. In his final decade, he turned from traditional features towards expanded cinema. In 2017, he created Till the End of the World at the EYE Film museum in Amsterdam—an exhibition that was part film, part theatre-set and part installation, built from found footage, fragments of his movies, props and a specially shot scene, assembled to give voice to millions who are denied dignity in Europe’s refugee crisis. In 2019, he made Missing People, a series of performances and installations involving 250 people experiencing homelessness in Vienna, where the urban site itself became a living tableau. Tarr spoke publicly in support of Gaza. His film.factory in Sarajevo, a city still marked by war, rejected cinema-as-careerism in favour of collective responsibility and in these expanded practices, Tarr refused compassion as consolation, insisting instead on art that remains austere, disquieting and true.

He is survived by Ágnes Hranitzky, his partner in life and work since 1978 and by the collaborators who made a cinema that have shown us ways to see. He is also survived by the seven-hour-and-twenty-five-minute fact of Sátántangó, by the whale in the truck, by the horse’s slowness, by takes that refuse to cut, by faces treated as landscapes, by a door that closes for what feels like hours, by cinema transformed into philosophy, by the insistence that time is the material of art, that slowness is a form of resistance, and that ‘Being’ reveals itself only to those willing to stay and stare. And, as a scholar of cinema who studies boredom as method, affect, and premise, I hold Béla Tarr as a lesson in thinking through images, through time, through cinema itself.

Tirna Chatterjee is an independent researcher and writer and has a Ph.D in Cinema Studies from School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU. Her thesis looked at boredom as a method for doing Cinema History.