Fossils' 'Bishakto Manush' and Britney Spears' 'Toxic' became a sensation at the turn of the millennium.

In the era of mass-produced romance, both Bishakto Manush and Toxic are hymns to the love you didn’t ask for and can’t escape.

Fossils offer darkness as catharsis, while Britney sells the dance floor as salvation.

Let’s time travel to the early days of Y2K. Out in the world, the glitter of the millennium is just starting to rub off, leaving behind one heck of a hangover. Two songs drop, both about the kind of love your therapist warns you about—one from the brooding, rain-glazed bylanes of post-colonial Kolkata, the other from the relentless sparkle of American pop. On one side, Fossils’ “Bishakto Manush”, 2001, a potent Bengali rock lament; on the other, Britney Spears’ “Toxic”, 2004, pure pop confection laced with venom and violins.

The two tracks come across as musical fraternal twins, separated at birth and raised by radically different godparents.

Opening Scene: Love Bites…But Who’s Chewing?

Here, we’re not talking about just another heartbreak ballad. Fossils erupted from the Bengali underground with the sort of psycho-sexual poetry you expect from Kafka in a rehearsal room with Jim Morrison: “green veins,” “bluish lips like snakebites.” This is love as contamination, obsession as incurable disease, where the lyrics evoke a cityscape thick with betrayal and existential angst. Meanwhile, Britney shimmies into the club, high on a cocktail of maximalist production and Bollywood strings. She’s not just “addicted”; she’s swaggering about with it. Swedish hitmakers, a dash of 1980s Bombay, and voila—you’re on a rollercoaster through candy-coated ruin. The twist? While Fossils belt confessions from the cracked sidewalks of Kolkata, Britney’s global hit is built on a sample swiped from India, the world’s largest underground outsourcing gig.

Kolkata’s Renaissance (Now with Extra Volume)

Early 2000s Kolkata was a city mid-makeover. Stale Marxism, colonial inertia were suddenly old news. Electric guitars and existential dread filled a vacuum left by the dying embers of the 1970s rock revolution. Fossils were not factory-assembled industry plants; they were the moldy vinyl in your uncle’s attic, excavated by hungry youth desperate for anthems that sounded like home. What they did was fuse Western rock’s catharsis with local pain, language, and dark alleyways, birthing an attitude that was one part rebellion, one part nostalgia, and a generous dose of “Screw it, let’s play loud." Their music was a wet paint sign slapped on Kolkata’s cultural walls: “Keep Off, Unless You Get It.”

Meanwhile, In Britneyland: The Pop Machine Hums

Britney never had the luxury of being misunderstood. By 2004, she was pop’s Mona Lisa: enigmatic, commodified, and crying mascara tears in prime time. Her metamorphosis from Disney cyborg to subversive pop star was less Hollywood fable, more capitalist alchemy, where even existential breakdowns could be spun into platinum. “Toxic” burst forth as a perfectly engineered product, an “authenticity” so well constructed that you could see the scaffolding. Producers stitched together Bollywood strings, surf guitars, and dance floor euphoria, all while Spears breathes into the mic like someone about to hand you a poisoned rose. This was desire, shrink-wrapped and ready for consumer adoration.

How To Stage A Love Affair: Gothic Gloom Vs. Glittery Apocalypse

Forget puppy love. In the world of Fossils, falling for someone is basically clinical. Think fever chart, not Valentine’s card. This isn’t slow-dancing in the rain; it’s waking up with bite marks, metaphysical vertigo, and a suspicion you might be infected. Every lyric doubles as a psychiatric case file: love as viral load, desire as the symptom. The city isn’t just a setting; it’s a quarantine zone. Mahabharata’s “chakrobuho” isn’t here as a nice metaphor but a coded warning against the labyrinth of uncomfortable feelings and words spewed out by the throaty frontman. These aren’t polished rockers; rather, they’re the last survivors of an emotional apocalypse, black t-shirts sweat-stained from last night’s gig, eyes wild with whatever toxic prophecy they crooned into the sticky Calcutta midnight.

Britney: Addiction With A Smile And Glitter That Never Washes Off

Now cut to Britney: the original pop cyborg, slinging a beat so shimmery it could blind you at forty paces. In “Toxic,” addiction isn’t a crisis but the Pinterest goal. Who needs therapy when dependency sounds this catchy? Britney’s “zone” is not a place, it’s an algorithm: lips glossy, skin filtered, everything ready to go off or at least be manufactured into seventeen remixes. Her plea “Baby, can’t you see, I’m calling!” bears the double edge of a neon sign: both SOS and “open 24 hours.” This is the genius of Spears-era capitalism: empowerment and entrapment, gift-wrapped as self-care. You boom along to her tune, unbothered that the cage you’re dancing in is lined with feathers and gold.

So, here’s the punch: Fossils hand you a love affair that feels like a blackout in the fever ward, while Britney pours your poison in a designer glass, twirling all the while. Both offer the same thrill where one wants you to sweat it out; the other wants you to sparkle until you drop. This isn’t just about masculinity and femininity trading winks across the stage. It’s about where those stories get told: Fossils make the toxic lover a spectral anti-hero everyone in the room recognises; Britney’s “Toxic” is the male gaze swung back, refracting, becoming weaponised.

Institutions And Outsiders: Postcolonial Headbangs vs. Late-Capitalist Backflips

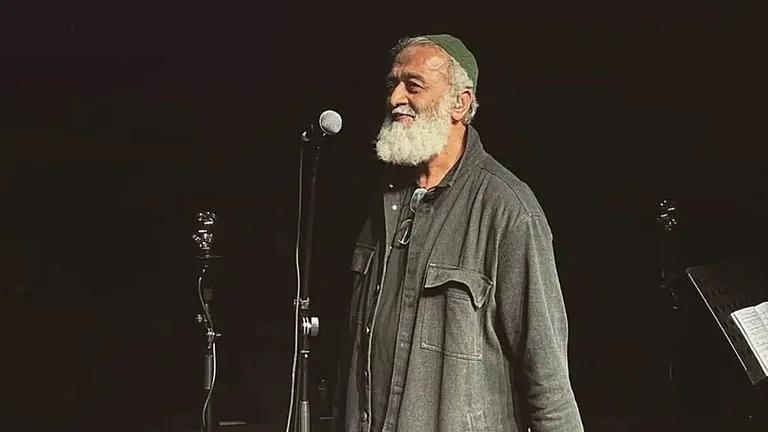

Fossils’ early days came out of grinding it out in dingy clubs, college fests, and local festivals with microphones held together by hope and duct tape. Authenticity was but a survival strategy: recording live and letting the tape hiss next to the guitar feedback. Bengali rock, long relegated to obscurity, became suddenly dangerous again in the best possible way. Britney, in contrast, is all about the performance of danger. Everything about her trajectory shimmers with the possibility of collapse. When “Toxic” lands, it’s not just a song, it’s a signpost for every argument about what happens when the pop machine consumes its stars, chews on them, then feeds them back to us, pre-digested.

Fossils’ rise was a resistance of sorts—Bengali lyrics, Kolkata stories, a big “No, thanks” to Western-style pop’s domination. Their music became a ragged border fence against cultural erasure; a soundtrack for a generation figuring out how to be global, Bengali, and pissed off, all at once. Britney? She’s the glittering beast that eats resistance for breakfast. Even as “Toxic” critiques the cult of desire, it’s already been monetised, branded, and sold back to us as empowerment. Call it late-stage capitalism’s biggest magic trick—sell the poison and the cure in a single track.

The Long Afterlife: Two Types Of Poison, Two Paradises Lost

Fast forward to now: “Bishakto Manush” has a legendary status. It is oft-quoted, imitated and sung along to. The rawness and weirdness have aged well. It’s a beacon for every garage band that thinks the local is enough because, sometimes, it is. “Toxic” sits on countless “best-of” lists and academic takes, but its legacy is tangled up with Britney’s public unravelling and her fight for personhood over persona. Her greatest hit is now a monument to the perils of stardom and the teeth of the machine that made her.

Final Bang: On The Art Of Loving Poison

Here’s the twist: you cannot un-hear either song. In the era of mass-produced romance, both Bishakto Manush and Toxic are hymns to the love you didn’t ask for and can’t escape. This isn’t eros mythologised; it’s desire metabolised. This is alchemy where poison tastes like revelation, where danger becomes the truth. From the alleyways of millennial Calcutta, Fossils pulls you into a confessional booth lit by neon and regret, insisting that to love is to court contagion, to dance with the ruinous. Britney, America’s glittered oracle, flips the narrative: if you can’t escape the toxin, why not make it a hit? Her version is a VIP lounge where damnation comes with a disco beat, so why not embrace the end in sequins?

But both, at heart, are con artists: Fossils offer darkness as catharsis, Britney sells the dance floor as salvation. Neither is telling the truth. Dark rooms and discos, after all, are both escape hatches from the same mundane, each a hall of mirrors where the poison is the point, and redemption is just another lyrical discretion. The real work isn’t surviving poison, but learning to sing its praises unblinkingly. In Bengali rock’s growl and global pop’s gloss, the most radical act is admitting the lie: beauty isn’t the antidote to danger; perhaps, it’s what makes danger survivable. And so we return: not healed, but haunted, not saved, but sanctified by the sheer, reckless act of singing along.

Tirna Chatterjee has a PhD in Cinema Studies from School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU. She currently works as an Associate Manager at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity.