It was in the 19th century that new theories about Indian languages took shape. Grammar and literary treatises of Indian languages were printed.

The Dravidian movement can take credit for using treadle printing machines—used locally only for printing wedding invitations—to print pamphlets and magazines.

Cinema, which arrived in Tamil Nadu in the 1930s as a modern, technology-driven art form, was used with remarkable effectiveness by the Dravidian movement leaders from the early 1950s.

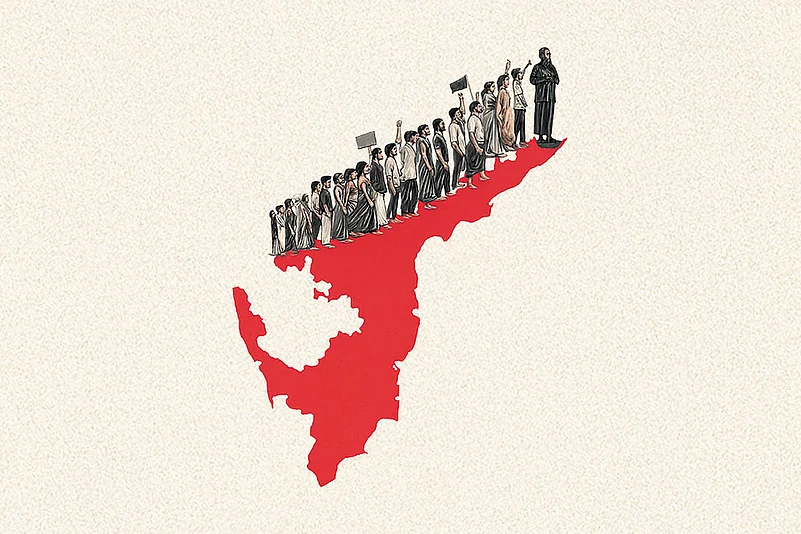

Thanthai Periyar launched the Self-Respect Movement in 1925 after quitting the Congress. It later evolved into the Dravidar Kazhagam (DK) and then the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). The All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) was also a continuation of that legacy. It is now nearly a 100 years since the movement was launched, and about 60 years since it first came to power. Today, the DMK, which rules Tamil Nadu, identifies its governance as the “Dravidian Model”.

The reason this century-old movement continues to remain so strong is the support and influence of the people. Through its ideology and its actions, the Dravidian philosophy has reached all sections of society ranging from scholars to ordinary citizens. How did this widespread reach happen?

In the latter half of the 19th century, a consciousness about gaining freedom from British rule began to emerge in India. When movements and protests for independence started rising, the British countered them with the argument that “Indians were not fit to govern themselves; they have no such historical tradition”. This claim was repeatedly asserted and propagated. As a response, a strong awareness arose among Indian scholars about their own history. It can be said that this period was, in every sense, a fertile moment for the formation of Indian history.

It was in the 19th century that new theories about Indian languages took shape. Grammar and literary treatises of Indian languages were printed. Discoveries of inscriptions and copper plates came to light. The architectural and sculptural wealth of temples and palaces began to be documented in the public sphere. Ancient coins were unearthed. Information about administrative systems was found. Using all these as evidence, scholars produced research to establish that India indeed had a long and rich history. Historical works began to emerge. Although those involved in writing Indian history did not pay much attention to the southern region, people from Tamil Nadu did not remain passive. There was abundant material to write separately about the Tamil language and about Tamil Nadu. Research studies and historical works emerged from this context.

Meanwhile, non-Brahmins educated in institutions established by the British began raising their voices demanding space and opportunities for themselves. The Non-Brahmin Movement, which began in 1917, and later evolved into the Justice Party, played a significant role in this regard. Keeping all this background in mind, the Self-Respect Movement made effective use of it.

Drawing upon the oppositional frameworks of Dravidian and Aryan, Dravidian languages and Indo-Aryan languages, Tamil and Sanskrit, and non-Brahmin and Brahmin, the movement shaped its ideological foundations. To take these ideas to the masses, public speeches became the primary tool. Stages were set up in simple, low-cost ways. Often, speeches were delivered even without a formal stage by standing at three-road or four-road junctions. Speakers would raise their voices and speak loudly, almost in the style of therukoothu (street theatre), so that people far away could hear them.

Using loudspeakers was an expensive affair in those days. Gradually, through public donations, arrangements for stages and loudspeakers began to take shape. A stage was not merely a place to deliver speeches; several elements came together to form what can be called a “stage culture”.

Several people would sit on the chairs placed on the stage. Everyone associated with the event would be given a place on the stage. Each speaker would first name every person seated there along with their designation, addressing them respectfully as avargale. Likewise, whether a person spoke or not, they would be honoured on stage with a ponnadai (ceremonial shawl) in appreciation of their contribution.

These practices continue even today on the Dravidian political stage. Other political parties, knowingly or unknowingly, have also felt compelled to adopt such conventions. Today, if such practices are followed in literary events or academic conferences, they are often viewed with sarcasm or criticism. One must understand that this attitude itself is a result of the influence of Dravidian stage culture. Why are chairs provided for everyone on the stage? In a society divided by caste hierarchies, the stage becomes a space of equality. Everyone involved in the event receives some form of recognition. Even though it may be just a low-cost piece of cloth, it takes on the symbolic meaning of a ponnadai. At a time when many caste groups were not even allowed to drape a cloth over their shoulders, the ponnadai became a powerful marker of dignity.

The respect conveyed to each person, addressed as avargale, is also noteworthy. In contrast to the Congress party, which was dominated by landlords and zamindars, the Dravidian movement gave prominence to ordinary people. Meetings would run for two to three hours. Before the main speaker arrived, several local leaders would speak. Their speeches would combine Dravidian ideological positions with local issues. Many people became seasoned speakers through this platform. These speakers emerged as one of the strengths of the Dravidian movement.

Periyar started the Self-Respect Movement only at the age of 46. He lived till 94. Having founded the movement, he spent nearly 50 years of his life continuously speaking in public spaces. It is said that he addressed more than 10,000 meetings. Every year, he spoke at more than 200 gatherings. He organised his entire daily life around this commitment. When his wife Nagammayar passed away, he wrote that “a major obstacle has been removed”.

Periyar did not want a separate house of his own, nor did he wish to live permanently in one place. He wanted to always be on the move. As long as Nagammayar was alive, these wishes could not be fully realised. After her death, he lived exactly as he wanted. Travelling, speaking at meetings, and staying in whichever town he happened to be, and this became his everyday routine.

If Periyar alone addressed so many meetings, one can safely say the total number would run into lakhs when we count the speeches delivered by the next generation of leaders. Bernard Bate, an American anthropologist, conducted research exclusively on Dravidian political oratory and has written extensively on the subject.

The Dravidian movement actively encouraged reading. At every meeting where Periyar spoke, low-cost pamphlets were sold. These were small booklets, usually 10 pages or fewer, containing one or two essays. They were easy for people to buy and easy to read. Pamphlet sales eventually became a part of all Dravidian movement gatherings. The organisation created space for a wide range of people to take up responsibilities. In every village, there would be one or two office-bearers. Even those without an official role earned the respected title of thondar (volunteer).

In the tradition of Tamil devotional literature, the word thondar meant “slave”, and thondu referred to servitude. The Tamil Lexicon, produced in the 1930s, gives “slave” as the meaning for both words. But the 1992 edition of the Cre-A Modern Tamil Dictionary records how their meanings had shifted: thondar now meant “a person who works in a political party or social organisation without pay”, and thondu meant “service performed selflessly, without expectation of benefit, for the welfare or growth of something”.

Clothing too played a role. Periyar made the black shirt and black towel identifiers of the Dravidian movement.

This shift or evolution in meaning was brought about by the Dravidian movement. It cannot be seen merely as a linguistic change. It was the Dravidian movement that transformed the meaning of the word thondar, making it refer to someone who works for the movement with ideological commitment. Expressions like “he is a Self-Respect Movement thondar”, “a Periyar thondar”, or “a Dravidian Movement thondar” became common. Even today, some elders are honoured with the title “Periyar perun-thondar” (great volunteer of Periyar). At the local level, the identity of being a thondar came to be regarded with great respect.

When leaders or speakers travelled to a village, they would stay in the homes of thondars; even if they stayed in a lodge, they would visit a thondar’s home for at least one meal. There are still families proudly saying, “Periyar stayed in our house,” “Anna ate in our home,” or “This is the place where Kalaignar sat.” This practice brought not just the individual, but the whole family into the movement’s activities. In the protests led by Periyar, his wife Nagammayar and his sister Kannammal also participated. Speaking about the toddy shop picketing agitation that Periyar organised during his time in the Congress, Mahatma Gandhi remarked, “That struggle in Erode is in the hands of two women.”

Not only Periyar’s family, but the families of Dravidian movement thondars too were actively involved in the movement. It became common for an entire family like husband, wife, and children to attend public meetings or conferences together. My father-in-law was a devoted volunteer of the movement. For conferences held in different towns, he would take the entire family along. He showed no particular interest in visiting temples or attending family functions. Party events always received priority. In March 1967, C. N. Annadurai was sworn in as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu. In 1968, celebrations were held to highlight the achievements of the first year of his government. My wife was born in March 1968. Believing that Annadurai’s government was shining like a radiant kingdom, my father-in-law named his daughter “Ezhilarasu” (beautiful/just ruler). Later, when she was admitted to school, the headmistress changed it to “Ezhilarasi”, saying that “Ezhilarasu” was also a boy’s name. This name is not just about an individual, it stands as a sign of how deeply the Dravidian movement had entered family life.

The daily routine of a Dravidian movement thondar included reading. He would subscribe to some magazines, and some others would arrive for free. These magazines would be spread out in the front veranda of his house. Anyone could pick them up and read. For those who could not read, the thondar or someone else would read aloud. After printing facilities improved, a type of “large-print books” emerged in Tamil. Popular folk stories and songs would be printed in large letters. Even someone who had learned only basic reading could manage them. In those days, when there was no electricity, these large-print books helped people read under the light of an oil lamp or lantern. The Dravidian movement nurtured and expanded this culture of one person reading while many gathered to listen. Even today, the DK continues to publish small booklets, which are sold at public meetings.

At this point, I feel compelled to share a personal experience. In the 1970s, when I was a school student, the person who encouraged me to read newspapers was my father. He was an ardent supporter of Anna. When M.G.R., after leaving the DMK, founded the AIADMK, my father joined it. At that time, in our village, only one house received daily newspapers. It belonged to a thondar who had participated in the anti-Hindi agitation and dedicated his entire life to the Dravidian movement. The house was a small structure. It was a thatched hut in the middle, surrounded by a fence of dried malangizhavai (Indian ash tree) shrubs. Under a neem tree, stones were arranged for people to sit. On a stone slab, a pile of newspapers would be placed. All of them were DMK-aligned magazines and publications, filled with strong criticism of the AIADMK and M.G.R. Yet my father encouraged me to go there and read. He himself did not know how to read a single letter. Sometimes, he would accompany me and ask me to read out the headlines. From those alone, he would launch into fierce critiques. If others happened to be there, heated arguments would break out. Through reading and listening in this manner, I gradually developed an interest in politics.

Not only in private homes but also in certain public spaces, reading became a shared activity. In small towns and rural centres, tea shops and barber shops that emerged during that period served as reading hubs. In many villages, the Dravidian movement was even colloquially referred to as the “barber’s party”. In several places, padippagam (reading rooms) functioned. These were small spaces where various newspapers and weekly magazines, often donated by someone, were made available. Anyone could walk in, read, and leave. They operated almost like mini-libraries.

Even if there was a place to read, a person to read aloud, and many gathered to listen, there still needed to be material to read. Under the title “Dravidian Movement Magazines”, several compilations and studies have appeared in Tamil. Reading them reveals that during the 20th century—particularly before the DMK came to power—those in the Dravidian movement had published hundreds of magazines.

The Dravidian movement can take credit for using treadle printing machines—used locally only for printing wedding invitations—to print pamphlets and magazines. Most people know publications like Kudi Arasu, Viduthalai, Dravida Nadu, Nam Naadu, and Murasoli. But if one were to list out others like Pagutharivu, Manram, Nayaru, Thaay Naadu, Kural Malar, Kural Murasu, Ina Mozhakkam, Munnani, Theeppori, Theechudar, Puduvai Murasu, Mullai, Kuyil, Kalaimandram, Kathir, Thani Arasu, Nagara Dhoodhan, Sindhanaialan, Porvaal, Pudu Vaazhvu, Thennagam, Arappor and Thozhan, the list would be endless. Every leader known within the Dravidian movement has, at some stage, either run a magazine or served as an editor. These magazines not only published ideological articles and news reports, but also detailed the leaders’ schedules and summaries of their speeches. After reading such announcements, groups of young people would cycle to nearby towns to participate in the meetings. These gatherings included cultural performances and plays as well. In some meetings, even weddings were conducted. A public meeting was not merely a place for speeches: it functioned as a cultural stage with many components.

Every leader known within the Dravidian movement has, at some stage, either run a magazine or served as an editor.

Clothing, too, played a role in helping the Dravidian movement reach ordinary people. Items like the veshti (dhoti), shirt, and towel, which earlier were worn only during festivals or family events, became everyday attire. Periyar made the black shirt and black towel identifiers of the Dravidian movement. After the DMK was founded, veshti and towel woven with black and red borders, the colours of the party flag, became symbols of party identity for its cadres.

A new phrase, karaivetti (bordered veshti), even entered Tamil vocabulary. Expressing condolences on the death of a DMK volunteer, Tamil Nadu Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin wrote on Facebook (August 12, 2025): “I am saddened to hear of the passing of our pure-hearted comrade Sakthivel anna, who tied the black-and-red karai-veshti and brought many ashore.”

Even today, the karai-veshti remains a party symbol. Following the DMK, other political parties in Tamil Nadu too have adopted this karai-veshti culture. Speaking openly about everything is a trait shaped by Periyar. Wearing a veshti and towel that openly display one’s ideology and affiliation can be seen in this light. One could even say that the karai-veshti gave a kind of authority to ordinary people.

Among the current generation of Dravidian movement members, a different kind of change is visible in clothing. Some young ministers wear pants and shirts. Udhayanidhi Stalin often wears trousers and a white T-shirt bearing the “Rising Sun”, the DMK’s electoral symbol. Some individuals have even filed a case in the High Court arguing that he should not attend government functions wearing a T-shirt with the party emblem. Whatever the court’s decision may be, this situation stands as evidence that the Dravidian movement continues to regard clothing as a marker of identity.

Drama, cinema, and modern literature also played major roles in the spread of the Dravidian movement. Drawing upon the richness of ancient Tamil literature, the movement constructed ideas of Tamil greatness and antiquity. At the same time, it used modern literary forms to disseminate its views. Annadurai wrote several novels, plays, and more than a 100 short stories. The DMK’s former chief M. Karunanidhi’s contribution was equally significant. Writers like S. S. Thennarasu and T. K. Sreenivasan focused extensively on modern literature. Critics often dismissed or categorised these works as “propaganda literature”. Though opinions differ about their literary merit, no one can deny that they greatly aided the movement’s activism.

The plays written by these authors were staged widely. Numerous theatre troupes emerged. Productions by celebrated actors like M. R. Radha and N. S. Krishnan were especially important. Many individuals even ran their own drama companies. Bharathidasan’s play Iranian Allathu Inaiyatra Veeran (Iraniyan or the Matchless Hero) was banned by the government. M. R. Radha staged Keemayanam, a parody of the Ramayana written by Tiruvarur Thangarasu. That too was banned. Defying the ban, he continued to stage the play under different titles.

Cinema, which arrived in Tamil Nadu in the 1930s as a modern, technology-driven art form, was used with remarkable effectiveness by the Dravidian movement leaders from the early 1950s. Sensing the enormous reach and influence of cinema, members of the movement became deeply involved in it. Films for which Annadurai and Karunanidhi wrote stories and dialogues were released. In the 1950s, Karunanidhi became one of the most celebrated story and dialogue writers. The film Parasakthi, written by him and introducing Sivaji Ganesan, created a major controversy. Attempts were even made to ban it.

Hero-actors like K. R. Ramasamy, S. S. Rajendran, and M.G.R. strongly voiced Dravidian movement ideas in their films. Between 1950 and 1970, the influence of the Dravidian movement in the film industry was immense. Heroes were given names like Udhayasooriyan (Rising Sun) and Kathiravan (Sun). Scenes featuring the DMK flag appeared. Song lyrics contained indirect praise of the Dravidian movement.

M. R. Radha’s famous play Raththa Kanneer was made into a film, filled with rationalist dialogues. A film in which M.G.R. acted was titled Kanchi Thalaivan with reference to Annadurai. M.G.R appeared in a song sequence starting with the line “Naan paditthēn Kaanjiyilē” (I had studied in Kanchi). Cinema became a major instrument to spread the ideas of the Dravidian movement. Thus, the history of how the Dravidian movement became a powerful mass movement is vast. To understand its many dimensions, one must explore written documents. But those alone are not enough; extensive field research is also essential.

(Views expressed are personal)

This story appeared as An Equal Stage in Outlook’s December 11 issue, Dravida, which captures these tensions that shape the state at this crossroads as it chronicles the past and future of Dravidian politics in the state.