Periyar’s ideas on caste and equality are reaching Gen Z through social media and digital platforms.

Young people engage with his work to challenge inherited hierarchies and advocate for social justice.

His legacy endures as a method: question authority, demand dignity, and pursue equality.

Seyed Mubarak Abbas, now 30, first encountered Periyar’s ideas at around the age of twenty during the Kudankulam protests in Tirunelveli. Until then, although caste had quietly shaped his childhood, he had grown up without recognising it for what it was. He recalls being discouraged from speaking to certain people or visiting certain homes, including that of a Dalit friend he dearly wished to see. At the time, he did not understand why.

The protests changed this. They introduced Abbas to activists and community leaders who spoke openly about caste inequality and Periyar’s philosophy. Wanting to understand more, he began reading Periyar’s works, starting with Periyar Indrum Endrum (Periyar Today and Forever). For Abbas, it was the first book that brought everything into focus: the idea that no one is born superior or inferior, that no person is another’s subordinate, and that discrimination is not culture but wrongdoing.

His journey forms part of a wider trend. According to Vignesh Karthik K. R., author of The Dravidian Pathway and a postdoctoral research affiliate at Leiden University, younger Tamils are discovering Periyar in ways distinct from previous generations. For their parents and grandparents, he notes, Periyar was “a living presence or a recent memory… someone you either revered or denounced depending on your commitment to equality or to hierarchy.” Responses to him were often inherited alongside caste, gender roles and political loyalties. Today, however, Periyar reaches younger people through books, study circles, Instagram reels, YouTube snippets, memes, podcasts and subtitled speeches.

Political Climate And The Revival Of Interest

Mano Thangaraj, the 58-year-old Minister for Milk and Dairy Development and DMK MLA from Padmanabhapuram, observes that younger generations encounter Periyar very differently from earlier decades. “Millennials and Gen Z engage with Periyar mainly through social media, memes, podcasts and online debates rather than party meetings and books,” he said.

They relate his ideas to contemporary concerns such as gender equality, personal freedom, mental health and LGBTQ+ rights, and often read him alongside Ambedkar, feminist writers and global social-justice movements. Their engagement is issue-based rather than party-driven, particularly around caste, NEET and student politics. As Thangaraj put it, young people connect with Periyar by breaking away from entrenched caste, gender and racial assumptions.

Karthick Ram Manoharan, Assistant Professor at the National Law School of India University, offers a similar view. “Periyar’s popularity and reach are at an all-time high. For decades after his death, he was largely remembered only on special occasions, and intellectual engagement with him was limited. A key credit for the revival of interest in Periyar goes to Prime Minister Modi. The rise of the BJP has led progressive youth to search for other ideas. Periyar comes in handy.”

Vignesh observes that young people approach Periyar with curiosity rather than inherited reverence or inherited contempt. They “engage with a set of arguments,” he says, “testing them against their own lives rather than defending or rejecting a leader.” This shift is rooted in the social pressures they confront. Persistent inequalities linked to caste, gender and religion continue to shape access to education, workplaces, public spaces and even personal relationships.

Academics note that Periyar’s arguments are far more nuanced than the sensationalised fragments that often dominate online debate. Manoharan points out that while Periyar’s popularity is soaring, his subtler analysis of caste power often goes unnoticed. His iconoclasm, he argues, was not a gesture for shock value but a rigorous critique of caste and patriarchal structures. Periyar’s anti-caste positions may resonate strongly with youth in towns and cities, while his libertarian approach to marriage and sex may appeal to a more cosmopolitan audience.

For many, Periyar offers not just inspiration but a framework, a vocabulary with which contemporary injustices can be named. Yet the same digital platforms that have broadened his reach have also distorted him. Selective clips circulate easily, often deployed by those invested in preserving the hierarchies he opposed. As Vignesh notes, this has created a strange duality: wider access to his works but greater susceptibility to misrepresentation.

For Abbas, this questioning also unsettled family life. His changed understanding initially disturbed his parents, though they eventually accepted his views. When he moved to Chennai at 22 to work in a library, he connected with groups such as the May 17 Movement (a Tamil nationalist organisation) and the Thanthai Periyar Dravidar Kazhagam, deepening his commitment to anti-caste principles. Alongside this political awareness, he now runs the Karunai Ullangal Trust, an NGO he founded in 2015. It supports homeless and abandoned people and also helps cremate unclaimed bodies.

Politicians Recount Their Own Encounters With Periyar

Politicians, too, observe a generational shift. Sasikanth Senthil, Congress MP for Tiruvallur, recalls that while growing up near Chennai he was more aware of class than caste, only later realising that caste was the deeper obstacle to equality. His engagement with Periyar began in the early 1990s when he encountered Dravida Kazhagam booklets of Periyar’s speeches. One that stayed with him was Pen Yen Adimai Annal, which set out the intertwined nature of patriarchy, caste and religious ritual. Periyar, he says, “was the first to articulate how patriarchy is enforced through caste and sustained by religious ritual, and to oppose all three on the same plane.” What impressed him most was that Periyar’s writing in the movement newspaper Viduthalai was simple, grounded and driven by the belief that nothing mattered more than self-respect.

These themes echo in the broader political landscape. Kalanidhi Veeraswamy, MP for Chennai North, notes that “many young voters have little sense of the history or significance of Tamil Nadu’s Self-Respect Movement.”

This concern has prompted Deputy Chief Minister Udhayanidhi Stalin to initiate outreach programmes explaining the movement’s legacy. At these meetings, a familiar question recurs: how many of your parents or grandparents had access to education? The answers often reveal why affirmative measures were introduced and why they continue to exist, Veeraswamy explained.

Dravidian Policies That Carry Periyar’s Legacy

Dravidian parties have carried Periyar’s ideas forward through policies on social justice, caste reform, rationalism and women’s empowerment. According to Thangaraj, “they institutionalised his principles through reservations, anti-caste laws, language rights and state-sponsored welfare schemes”. His ideas continue to shape public life through events, discussions, statues and school textbooks, and party leaders often draw on his writings in debates and manifestos. This sustained political, cultural and educational engagement, Thangaraj said, has kept Periyar relevant across decades.

Current government schemes continue this trajectory. Initiatives such as the Puthumai Penn Thittam, extended to boys through the Tamil Puthalvan Thittam, provide monthly support for higher education. The New Entrepreneur-cum-Enterprise Development Scheme (NEEDS) helps first-generation entrepreneurs launch businesses. The Valarthu Kattuvom Thittam offers subsidised loans for new enterprises. Rural women receive additional support through initiatives such as the Tamil Nadu Rural Transformation Project, which includes a matching-grant component, and through platforms like the TN-RISE Women Start-up Council, which aims to empower rural women entrepreneurs.

Free bus travel for women is designed to enhance mobility and economic autonomy. Combined with steady economic growth, these policies are presented as evidence of a sustained commitment to social progress.

Historical Roots Of Social Transformation

This struggle, rooted in the efforts of the Justice Party and sharpened by Periyar’s critique, transformed Tamil Nadu’s social landscape. Veeraswamy pointed out that where Dalits were once barred from certain streets, Periyar argued that if religious texts sanctioned inequality, then those texts, and the gods behind them, must be scrutinised.

His instruction was simple: educate yourself, and ensure others can be educated too. This legacy shaped leaders such as K. Kamaraj, Veeraswamy noted, whose expansion of schooling underpins Tamil Nadu’s ongoing commitment to education. Today, the State remains a strong advocate of universal education, supported by mid-day meals and a significant welfare net. Its 69 per cent reservation policy also stems from this historical commitment to equity.

For many young readers, Periyar’s appeal rests on three qualities, says Vignesh Karthik. First, he believed no authority was beyond questioning, including his own. He revised his views when challenged and rejected followers who merely echoed him. This resonates with generations wary of grand narratives.

Second, his language was clear and accessible. He conveyed rationalist ideas through short essays, sharp humour and everyday examples. He did not write as a distant thinker but as someone interpreting ordinary village and working-class life, making him unusually approachable.

Third, he was clear about what he opposed and what he aimed to build. He saw caste, patriarchy and religious authority as structural systems rather than isolated prejudices, and sought solidarities among oppressed groups.

What makes him challenging is that he demands more than symbolic dissent. His critique extends to family, marriage, inheritance, temples, festivals and the notion of a benevolent community. Taking him seriously, Vignesh explains, means examining one’s own comfort and complicity, not merely condemning external wrongs. This kind of self-reflection is far harder than liking a post or sharing a quote; it requires ongoing awareness and a willingness to change.

At the heart of this political culture stands Periyar, whose most important contribution to modern Tamil social and political thought was his radical effort to rehumanise those dehumanised by caste. He diverged from many contemporaries by insisting that caste could not be dismantled without confronting patriarchy, religion and inherited social norms. Political freedom, he argued, was insufficient; only a social revolution grounded in personal autonomy could transform society.

A Movement That Evolves Across Generations

Thangaraj notes that the endurance of the Dravidian movement lies in its ability to adapt Periyar’s core principles—social justice, rationalism and self-respect—to changing social needs. “Beyond policy, the movement has lasted a century because each generation has reinterpreted these ideas,” he says.

From anti-caste mobilisation in the 1920s to welfare reforms in the 1970s, linguistic pride in the 1980s and today’s emphasis on inclusive development, the movement has continually reshaped itself. Thangaraj adds that cinema, literature and public debate have reinforced its values far beyond party politics. Its strength, he says, lies in its capacity to renew itself while remaining rooted in Periyar’s vision.

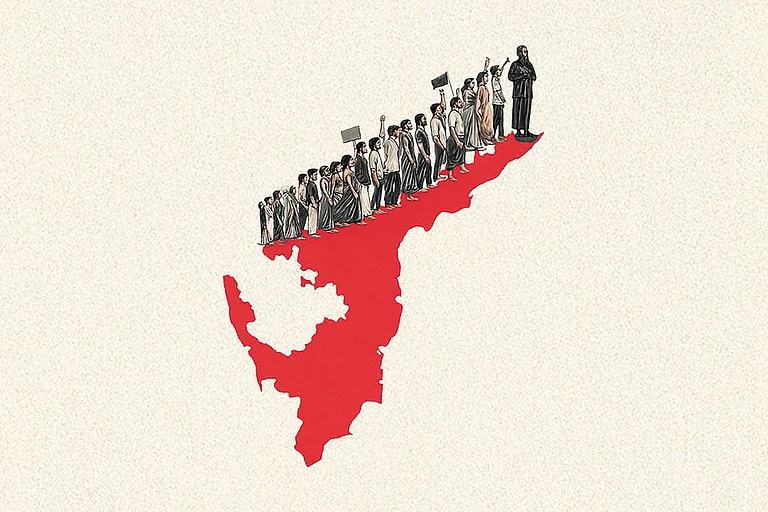

The Self-Respect Movement took shape in 1925 after Periyar’s break with the Congress, driven by its reluctance to confront caste or support proportional representation. From the outset, the movement articulated its principles clearly—rationalism, egalitarianism, anti-caste politics and the rejection of Brahminical authority. As K. Veeramani, president of the Dravidar Kazhagam, notes, its clarity stood in contrast to political groups that formed parties before defining their values.

Key Interventions and Political Developments

Throughout the late 1920s, Periyar and his colleagues intervened in major national debates: the Devadasi system, child marriage, the age of consent and the controversy generated by Katherine Mayo’s Mother India, a book that sharply criticised Indian society for its treatment of women and Dalits.

Periyar’s political leadership reshaped the early non-Brahmin movement. After taking charge of the Justice Party in 1939, he renamed it the Dravidar Kazhagam (DK). The DK became the ideological core of the Dravidian movement, advocating atheism, rationalism and the rejection of Brahminical dominance. Its refusal to participate in elections, however, led to the 1949 split, when C. N. Annadurai founded the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). Annadurai believed reform required engagement with India’s federal structure, a shift that helped shape modern Tamil Nadu.

Institutionalising Periyar’s Vision in Governance

Successive Dravidian parties—the DMK and later the AIADMK—carried elements of this legacy into governance. Although they moved away from the DK’s explicit atheism and anti-Brahmin rhetoric, they embedded social justice into State policy. Reservations expanded opportunities for backward classes, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Welfare programmes such as the mid-day meal scheme improved literacy, nutrition and social mobility. Initiatives like the Periyar Samathuvapuram were created to foster inter-caste harmony. Every district has at least two Samathuvapurams, and they have helped reduce caste divisions.

Tamil Nadu’s strong public distribution system, high school enrolment and assertive federalism all stem from this tradition.

Yet many inequalities the Self-Respect Movement sought to dismantle remain. Caste violence continues, and caste pride has re-emerged across communities. The struggle for substantive equality is unfinished, even though the Dravidian movement has undeniably weakened caste barriers and expanded avenues for dignity, education and mobility.

Periyar’s legacy endures not simply because he led a movement but because he offered a method: question every hierarchy, reject inherited authority and insist that dignity, reason and equality belong to everyone.

Manoharan warns that Periyar’s anti-religion stance, unsparing and uncompromising, sits uneasily in today’s national climate. “His views would be dangerous to express openly today.” Without the mass movement that once backed him, he adds, rationalist questioning becomes “just a difference of opinion.”

For young people like Abbas, Periyar is a voice that expanded his imagination, sharpened his political awareness and reshaped his understanding of himself and the world he inhabits.