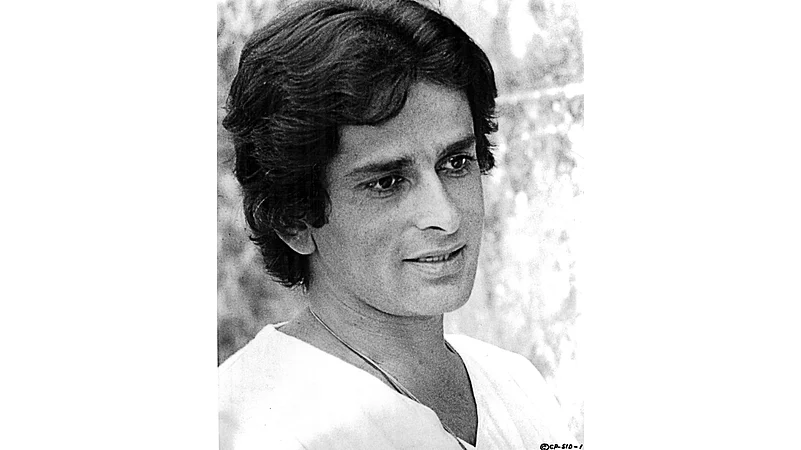

December 4 marks the 8th death anniversary of actor Shashi Kapoor.

His films with Merchant Ivory Productions mark a critical chapter in India’s cinematic history.

Prithvi theatre was established in 1978 by Kapoor and his partner, Jennifer Kapoor to honour the legacy of his father Prithviraj Kapoor.

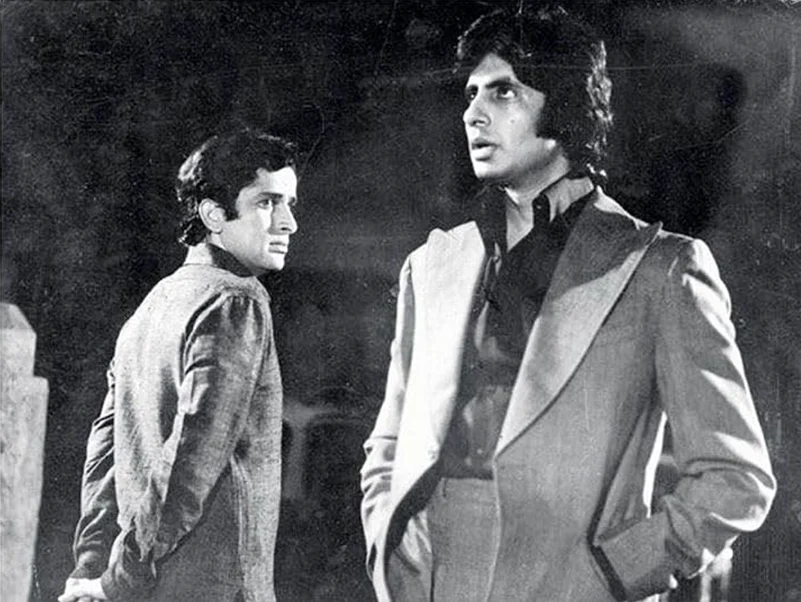

Would Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) have been the ‘angry young man’, had it not been for his righteous police officer brother, Ravi Verma reminding him why his turn as a criminal was problematic in Deewar (1975)? Or would the last exchange of gazes between Sudha (Rekha) and Mahendra (Naseeruddin Shah) in Ijaazat (1987) have the same poignant impact, had it not been for the love and charm of Sudha’s present husband entering the scene to pick her up, genuinely worried for his wife through a stormy night? Would Arjun Singh’s (Amitabh Bachchan’s) extreme loyalty and hilarity have engaged audiences enough, had it not been for Raja, the maalik he was so loyal to, in the mad mad Namak Halal (1982)? In all these dramatically different commercial films, Shashi Kapoor’s turns as Ravi, Raja and the nameless husband, amongst countless more, point at his charming presence and sophisticated craft. But more than that, they highlight the ability and confidence to appear in films of various kinds, produce some, and set them up in a way to spotlight others.

What changed through Kapoor’s illustrious and varied career is what he chose to draw attention to through his presence. In many commercial multi-starrers like Deewar (1975), Kabhie Kabhie (1976), Trishul (1978) and Kaala Pathhar (1978), he underscored the lead—like the angry young man, his discontentment with the realities of a failing and faltering system and the anger of the working class, amongst many others. When he played the moral compass of the society, he reflected the idealism that remained ingrained in the country and the ambition of a nation that still saw its future in a collective, based on values of togetherness, secularism and empathy. When he played the role of a privileged individual, he did so with a backstory, as a part of the system that benefited from the oppression of the underprivileged and recognised it. However, at every point, Kapoor’s characters remained empathetic and soft. Usually on the right side of the moral compass, on the right side of rules, he was the conformist—the one who still had hope from the idealism once worshipped. He was soft with women, charming and disarming.

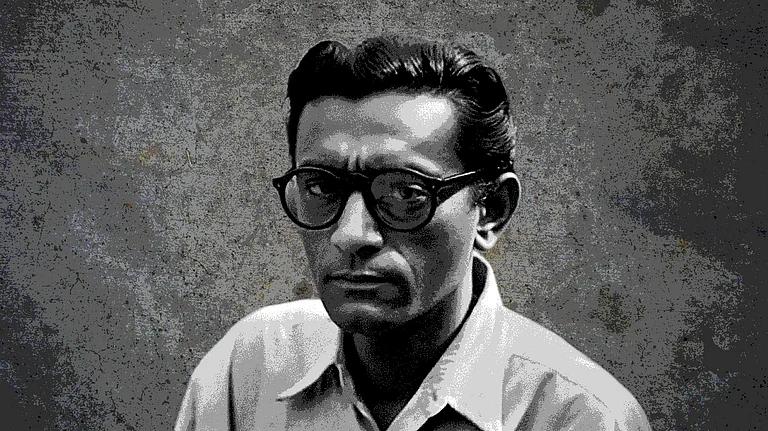

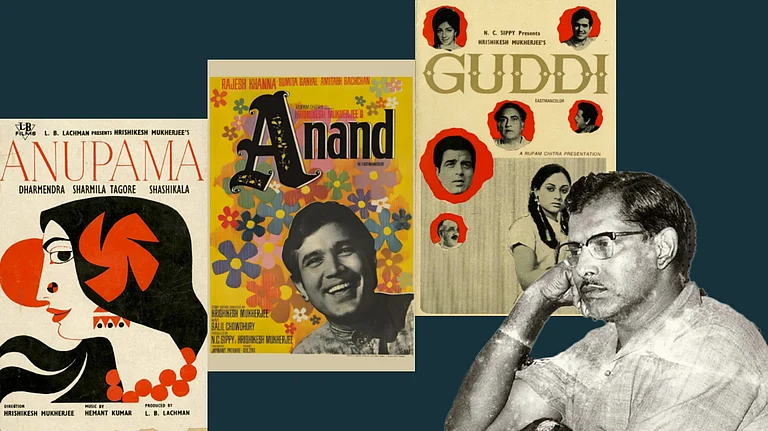

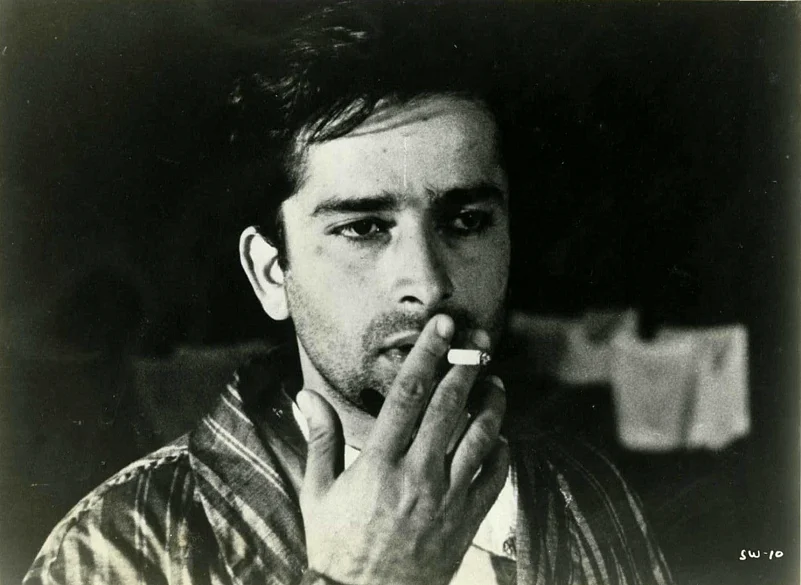

In his films with Merchant Ivory Productions—through which it can easily be argued that Kapoor was India’s first crossover star—he spotlighted the stories themselves. The films, which may not have otherwise been created as they were, mark a critical chapter in India’s cinematic history. Be it The Householder (1963), Shakespeare Wallah (1966) or Bombay Talkie (1970), these films had distinctive styles of storytelling, nuanced screenplays and detailed set designs, while being embedded in the artistic socio-political realities of the time. Collaborations with artists like James Ivory, Ismail Merchant, Satyajit Ray, Subrata Mitra, Ruth Jhabvala, the films were beautiful stories of nuanced human emotions, woven through delicate artistic narratives. Shakespeare Wallah, in particular, traces the travels of a theatre troupe performing Shakespeare in post-colonial India, set in the context of the rise of cinema, highlighting the struggles of art, performances and love in the context of changing cultures and expectations. These collaborations also drew artists of varied sensibilities together, bringing a distinct flavour to films never seen before or since.

Kapoor’s commitment to staging stories transcends mediums. As a producer, he was brave and brought to screens myriad visions of various directors for audiences. Creating alternate cinema would have needed brave producers to believe in the vision of its storytellers—those willing to have conversations that were away from the convention, from stories of the angry young man, or those of nation building. The stories Kapoor produced were aesthetically different and artistically courageous. He produced and starred in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1979) and Kalyug (1981), Govind Nihalani’s Vijeta (1982) and Girish Karnad’s Utsav (1984). Each of these films again point to exceptional collaborations, stemming from the world of theatre, with the likes of Girish Karnad, Satyadev Dubey, and of literature with Ismat Chughtai. The texts themselves were unconventional and bedrocks of theatre, whether it was Mrichhkatika that Utsav (1984) was based on, or Vyasa’s Mahabharata for Kalyug (1981). A dramatically different film he produced was 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981), which marked the debut of Aparna Sen as a director—a completely new distinct voice that went on to shape crucially the narrative of Bengal cinema, and by extension Indian cinema.

The metaphor of spotlighting is most apt for his greatest physical contribution to the world of theatre. A theatre space is most crucial for performers, practitioners and lovers. Prithvi theatre is not only a bastion of what spaces for theatre must look and feel like, but also what spaces for arts must enable—experimentation, free thought, festivals, free flowing of imagination and ideas, spaces for collaboration and community. Prithvi theatre was established in 1978 by Kapoor and his partner, Jennifer Kapoor. A testimony to Kapoor’s ability to honour legacies is to have named it Prithvi theatre as an extension of his father, Prithviraj Kapoor’s legacy who had founded the original Prithvi theatres. Over years, Prithvi theatre was turned into that essential oasis of the performing arts in Bombay by relentless efforts of Sanjna Kapoor, Sameera Iyengar and their team, which is now continued by Kunal Kapoor.

Kapoor was a truly consummate storyteller, who chose to spotlight others over self—other actors, narratives, stories. He chose to experiment as an actor, bring to the world stories seeped in art, and alternative narratives that needed canvases. In his choices, one can see the deep influences of theatre and literature and the tendency of bringing to the fore new voices. Artists who bring other artists to the fore, create stages and build these ecosystems are critical. Their contributions become legacies beyond their individual contributions as performances because they become enablers. To truly honour Kapoor’s contribution to the world of cinema, theatre and art, our society must create more artists.