Dev Anand was born on September 26, 1923.

In his early cinema, he dabbled in the noir thriller genre.

His experimentative streak was seen in many of his films, prominently Guide and Jewel Thief.

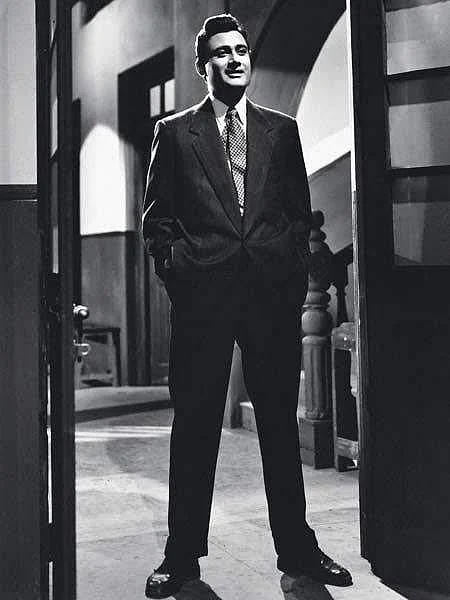

“Baazi dekhi hai tumne? Dev Anand ismein ek number ka juaari hai...kya kamaal ka karta hai woh, aur kya kamaal ka ladta hai, dikhaun kaise? Aise, jhoolte jhoolte, saamne se jitne chahein lampat kyun na aa jaayein, majaal hai koi uske baalon ka style bigaad de!” says a genuinely starstruck Dev, in Vikramaditya Motwane’s lovingly melancholic Lootera (2013). But that is the iconic style, the charm of the soft smile that not only created a fan base but also a significant chapter in commercial Hindi cinema—a new genre, off the beaten track.

Dev Anand’s initial protagonists weren’t conformists. Neither were they reformists changing oppressive systems, nor were they villains who created these systeams. He wasn’t the melancholic, reflective poet epitomised by Guru Dutt, nor was he the socialist voice of consciousness built by Raj Kapoor. Anand, instead, was an impish rogue—the one who flirted with the law, for his own gain; the one who protested the oppression of the system by using it to his advantage; by pushing power, as power watched itself being pushed. The noir genre was born with Anand, where grey characters played with boundaries of systems, recognising their power hierarchies and immense imbalances, which were fought against by being outsmarted. The rebellion was in being the loveable outlaw which gave Anand his unique identity that formed the definitive narratives of the 1950s and early 1960s commercial Hindi cinema landscapes, alongside the likes of Dilip Kumar, Dutt and Kapoor.

His early work Baazi (1951), directed by Dutt, was the first that set the tone for the genre. As the lucky gambler Madan, Anand infused the character with charm, humanity, empathy and style. The moody lighting of the film and the design of the narrative gave audiences a taste of noir. It was followed by Jaal (1952), again a Dutt film, which had stunning track shots, the trademark Dutt flair for visual poetry and the very stylish, yet good-for-nothing Tony, played with panache by Anand. C.I.D (1956), directed by Raj Khosla and produced by Dutt was a crime thriller that many count within the genre of noir. However, the key difference here was that the rogue was now the upholder of the law as the righteous inspector. We see Anand switch over to the role of the hero, while the genre of some of the films remain the same.

Taxi Driver (1954) produced under Navketan films and directed by Chetan Anand, is another important film in Anand’s repertoire. While the films being created by Dutt were creating a genre and persona, Taxi Driver, interestingly borrowed from the same characteristics of Anand as a hero—the trademark charm, panache, gait and style—but set him within the world of a relatable common person. And yet, the altruistic Mangal (hero) goes to visit a seductive club dancer every evening. These definitions of relationships that defied ideas of stereotypes and put humanity first, were crucial for social understanding and propelling conversations forward. Kala Pani (1958) and Kala Bazar (1960) follow the crime thriller genres. While Kala Pani has the protagonist again on the right side of the law, Kala Bazar explores what unemployment does and how difficulties push youth into crime. A meta film, it explores the temptation of what feels like a lucrative black market of film tickets, and his love interest becomes the moral compass that wakes his conscience to his own corruption.

Apart from the genre of the crime thriller, Anand was synonymous with romance and music. Irrespective of the genre of films—whether comedy, drama or even noir—his films have had songs that have stood the test of time. Whether it is “Yeh raat yeh chandni phir kahan”, whose visual poetry is etched in celluloid and in the minds of listeners and cinema lovers alike, or “Tadbeer se bigdi hui”, or “Abhi na jaao chhor kar” or “Chhor do aanchal”, the list is just endless. Almost every film of his has had incredibly memorable songs that are synonymous with his presence.

Dev Anand’s experimentative streak in his early work continued across many successful films that mark his career through the 1950s, well into the 1960s. However, when focusing on his ability to experiment and take risks, there are two films that must be specifically looked at—Guide (1965) and Jewel Thief (1967).

Guide (1965) is a landmark film on many accounts. It was a feminist film, where a woman chooses her love for dance over the idea of being with a man, is exuberant in her liberty and freedom and expresses that joy with “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai”, with its exceptional choreography. Waheeda Rehman’s performance in the film is for the ages, as is Dev Anand’s. But before we look at him as an actor in Guide, it is critical to appreciate him as a producer. To have chosen a script such as this and despite many exits from the project, to have stayed with it and ensured the film was completed, would’ve required conviction.

To represent a woman with agency, revelling in her choice of leaving a man (albeit encouraged and guided) in a patriarchal society like India, would have been a brave decision to take. As a hero, he is essentially an enabler throughout the film, who ends up renouncing life as he knew it. This was nothing like what Dev Anand had been seen as before. “Yahan kaun hai tera” lingers in audience’s minds long after it is over, with Anand’s face etched in memory. Guide changed the way characters were thought of. It gave an alternative of how women could be represented and what relationships could look like on screen. It needed a brave producer with vision, who could evaluate the strength of a story for it, which Anand had.

The second film is Jewel Thief (1967). It is often argued that many Hitchcockian influences shaped this film, along with other popular films from Hollywood. However, as one of the earliest heist films of Hindi cinema, it was yet another novel experience for audiences—a film with a tight screenplay, taut performances that kept the suspense going, and choreographies that are still etched in Hindi cinema’s hall of fame. Anand’s most critical films have had his female leads share an equally important part in making those films significant—and that too is an important reality of these films.

An artist remembered for his style, substance, panache and experiments, Anand was also invested in the politics of his country. As an active citizen, he opposed the Emergency and later also formed his own political party. As we remember Dev Anand, it is crucial to remember him as a conscious artist, who carried his political expression in art, and as a citizen, in life.