Summary of this article

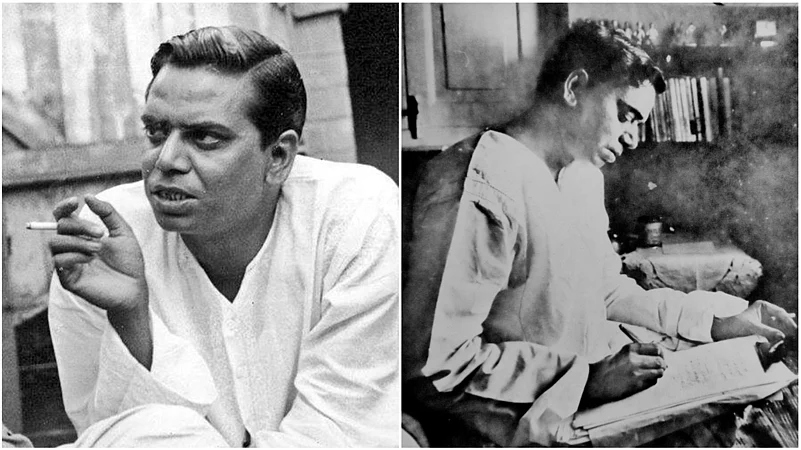

Poet and lyricist Shailendra passed away on December 14, 1966.

A member of IPTA, Shailendra's politics of being the voice of the oppressed was evident in his lyrics.

The songs he wrote brought to life truths that the world resonated with and found itself reflected in.

“Chhote se ghar mein gareeb ka beta,

Mai bhi hun maa ke naseeb ka beta,

Ranj-o-gham bachpan ke saathi,

Aandhiyon mein jali jeevan baati,

Bhookh ne hai bade pyaar se pala…”

These lines from “Dil ka haal suney dilwaala” from Shri 420 (1955) speak of class divides, lived experiences of poverty and its cyclical pain. They demonstrate Hindustani beautifully, with Urdu and Hindi idioms used one after the other. Shailendra, in his poetry and lyrics, had this unique ability to create layers of meaning by putting the simplest words together. The truths he told clearly in his lyrics have never been said as plainly and as comprehensibly before, or since. His politics of being the voice of the oppressed was evident, bringing to the fore various levels and complexities of oppression.

Shailendra’s identification of luck at birth also comes from his identity and struggles early in life. His deeply empathetic portrayal of oppression comes from his lived experiences as a Dalit progressive poet navigating life. As a welding apprentice in Central Railways, he came to Bombay and got involved with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Shailendra’s poetry and songs were simple but never simplistic and the folk nature helped them connect instantly. “Tu zinda hai, toh zindagi ki jeet pe yakeen kar, agar kahin hai swarg toh, utaar la zameen par’—a song that symbolises struggle, resistance, hope and defeating oppression to emerge victorious is one of the songs penned by him for IPTA.

His socialist thinking translated into his film lyrics as well. Some of the songs that have been written by Shailendra in cinema exhibit the ability to stretch from the reflective to the hopeful, from the touching to the rallying, all in the width of the same song. An extraordinary nature of his lyrics was that he would effortlessly move from the tiniest detail to the deepest philosophy, within a beat and the same idiom, keeping the layers of the meanings intact. For none of this did he rely on flair, similes or analogies, and neither on visual poetry or metaphors. He brought to life truths—truths that we chose to ignore, that privilege blinded us enough to miss, character arcs, their trepidations and fears, raw emotions wrapped in words, that the world resonated with, and found itself reflected in.

Awara (1951) saw the album divided between Shailendra and Hasrat Jaipuri. “Awara Hoon” carried the socialist truths in it—a hurt, pained, damaged, lovable and positive tramp spreading joy. The feelings carried the battered realities of an India waking up to its potential, but positive, and with values that radiated idealism and collective progress. It is important to note that one gets a glimpse of Shailendra’s immense range very early in his career—with Awara itself, as he writes Awara Hoon, and then the very romantic “Ghar aaya mera pardesi” and “Dum bhar jo udhar moonh phere” in the same film.

“Apni kahaani chhod jaa, Kuchh to nishaani chhod jaa, Kaun kahe is or, Tu phir aaye na aaye, Mausam bitaa jaaye, Mausam bitaa jaaye” from Do Bigha Zameen (1953) plays as Shambhu (Balraj Sahni) leaves his village for the unknown, merciless city where he has to go to earn money to save his land in the village. The juxtaposition of the lines, asking him to leave behind an imprint and consider a possibility of no return, recognise how brutal and difficult the journey that he is embarking on can be—that it can cost him his future and life. And yet the song speaks of flowers and birdsongs.

Boot Polish (1954), Shree 420 (1955), Jagte Raho (1956) are very interesting films to understand Shailendra’s socialist thinking and impact in cinema. It is fascinating to also note his range, his ability to juxtapose complete opposite genres to create absolute magic (classical with comedy) and understanding and use of folk. In Boot Polish’s “Lapak Jhapak tu aa re badarwa”, sung by the master of classical music Manna Dey, Shailendra has lines inviting the clouds to burst, to grow hair on bald heads! The layers of comedy and commentary become even more special when one notices the specificity of the song—set in a jail, with it being sung by a qaidi wearing 420 on his uniform (David). In Shree 420, it is the same person who gives us the great ballad of love “Pyaar hua iqrar hua hai” and the deeply political “Dil ka haal sune dilwaala” as well as “Ramaiya vastavaiya” that evokes the sense of folk and community and “Mud mud ke na dekh”, which is both the literal and philosophical, as steps have been taken by the protagonist on a road that will lead him to a different life. The texture of this song reflects the change in class of where it is being performed, as does the tempo and the music. In Jagte Raho, “Mai jhooth boleya” is a crucial song. A piercing commentary on the class inequality and on the privileged classes by the oppressed classes, it is wrapped in folk. An important political statement, it firmly keeps the gaze where it must stay—with the working class. All these films, and Shailendra’s lyrics, voiced the struggles of the working class, now eclipsed deliberately from mainstream Hindi cinema.

Shailendra’s interpersonal romantic songs also have varied shades, whether it was in intensity or imagery or even in mood. Be it “Yeh raat bheegi bheegi” from Chori Chori (1956) or the sublimely intense “Yeh mera deewanapan hai” from Yahudi (1958), or even “Khoya Khoya Chand” from Kaala Bazaar (1960), one can see the perceptible change in vocabulary of the expressions. His ability to bring opposites together and break meters, along with his trademark simplicity and his extreme vocabulary make him one of the most versatile and one of the greatest lyricists of Hindi cinema.

To say that Guide (1965) is a milestone of Hindi cinema is stating the obvious. A film that spoke of female desire, ambition, moving away from a marriage essentially because she was unhappy—the joy of liberation was all seen on screen beautifully. But it would’ve been incomplete without “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai” that encapsulated the liberation and the feeling of wanting to live for one’s own desires with such beauty and empathy. In “Piya tose naina laage re” that showcases both Rosie’s (Waheeda Rehman) dance prowess, increase in popularity and the passage of time, Shailendra deftly uses seasons and festivals. Weaving the idea of love, longing and waiting, keeping the song consistent through its changes, indicates his marvellous hold on the language and craft. “Gaata rahe mera dil” and “Tere mere sapne” are both beautiful romantic songs but with distinct flavours. While one celebrates the joy of love, the other promises the stability of it. Shailendra’s odes to the divine are also visible in Guide, with “Allah megh de” and “Hey Ram Hamare Ramchandra”. “Allah Megh De” brings into context the suffering of the poor without water. But the song that encompasses the philosophy of life, the character arc for Raju (Dev Anand) and reflects on the larger purposes and meanings of existence is “Wahan kaun hai tera musafir, jaayega kahan”. Each word, each line strings together immense depth and reflection with utmost simplicity.

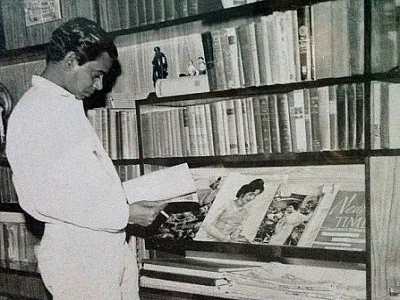

Shailendra produced Teesri Kasam (1966), a powerful adaptation of Mare Gaye Gulfam. The film failed at the box office then, but won a national award, and enjoys a cult status now. It was an empathetic take on prejudices, working class and idealism. But the financial loss of the film impacted Shailendra deeply.

“Jeena yahan marna yahan” from Mera Naam Joker (1970) marks the end of Shailendra’s life and career as a lyricist. It feels poignant and ironic that a song that wraps the philosophy of life and the stage, the circus and the circus of life in poignancy and hope marks the end of Shailendra’s life as well. But every line of this song is a befitting tribute to the man who gave us a world of words to express raw emotions empathetically. He encouraged us to see the world in its nuances, and yet with hope—not as it is, but as it could be. And despite all the complexities, to try and attempt telling the most difficult, harsh and complex truths simply.