Summary of this article

Tarkovsky’s Stalker, forged through production chaos, presents the Zone as a living, sentient landscape where a quest for desire becomes a meditation on fear, faith and human fragility.

The film’s toxic afterlife, marked by the deaths of its makers and echoes of disasters like Chernobyl, lends it an eerie prophetic quality about moral decay and authoritarian power.

Though rooted in Soviet imagery, Stalker resonates deeply in the subcontinent, where its vision of spiritual and psychological entrapment mirrors contemporary reality.

In 1979, Andrei Tarkovsky, the great Russian filmmaker, completed Stalker, the last film he would make in his homeland. The film was loosely based on a 1972 novel by the Strugatsky brothers called Roadside Picnic. As with Tarkovsky’s earlier film, the epic Andrei Rublev, this film, too, had a maddeningly difficult route to completion: the first attempt at making the film took almost a year, but the negative processing turned out to be flawed and the whole thing had to be re-shot; there are different versions that recount the parting of ways between Tarkovsky and his cinematographer; likewise, the script apparently changed considerably by the second attempt and, depending on who you believe, the film was either identical to the first version or completely different from it. In any case, despite the hugely bumpy journey, what finally emerged on the screen was one of the most powerful fiction films ever made.

The eponymous Stalker is a guide, a bit like a wildlife guide, who illegally takes visitors into a prohibited zone, sneaking them in past the military patrolling the perimeter, soldiers under orders to use terminal force to stop people entering this deadly area. Exactly why the zone is dangerous and out of bounds stays unclear through the film, but the uninhabited wasteland, littered with ghosts of rail lines, water channels and industrial plants, is booby-trapped with a number of lethal obstacles and physical phenomena that could have been brought about by human error on a massive scale, extraterrestrial activity or some other undefined agency. At the centre of the zone is a room. Each visitor is desperate to reach this room because it apparently fulfils their innermost desires once they are inside. In the film, Stalker takes two men, a scientist and a writer, into the deepest core of this post-apocalyptic maze.

This being a Tarkovsky film, there is no straightforward denouement to this wild take on the classic search for the Holy Grail. Suffice it to say that as the film unfolds, we understand that it is not only the human characters but the entire zone that is somehow alive; the possibly radioactive factory—skeletons, the streams covered with toxic foam, the dunes of unidentified material, any of it could be somehow sentient and able to interact in terrifyingly unexpected ways with the consciousness of the human protagonists. By the last sequence, you are back outside the zone, in a gloomy, dingy house in the village just outside the boundary: a little girl, the Stalker’s daughter, tilts her head and stares at some empty glasses on the dining table; the glasses begin to slide across the surface; a slow freight train passes somewhere outside the frame and for a moment you think it is the vibration from the rail tracks that’s causing the glasses to move but then you realise, no, it’s the girl who is slowly pushing them to the edge.

Like the stories about the Englishmen who opened Tutankhamun’s tomb, the filming of Stalker also has a spooky half-life that continues after the release of the film. Just a few years after its completion, Tarkovsky, his wife and various members of the crew die prematurely from cancers that were very likely triggered by the toxic exposure they faced on the actual, heavily polluted locations around the fraying, collapsing Soviet Union. Just a few months before he died in self-chosen exile in Paris, Tarkovsky witnesses the disaster that unfolds at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in his homeland, an event that many connect to the varieties of dark prescience they find in Stalker. At a deeper, less literal level, one can also see the film as a kind of anticipatory allegory for the rise of Vladimir Putin and this Russia ruled by obscene greed, cruelty and fear.

The palette of the film is the most un-subcontinental one you can imagine: brittle, cold greys and browns, dirty whites and even filthier blacks; a kind of sick blue light that pervades the spaces, the rain and semi-snow of the northern latitudes with the sun taken hostage by the brutal winter; the pallor on the Caucasian skin almost bleached of all human colour; and yet, something about the griminess of spirit, the desperation of people whittled away by overwhelming circumstances, the fact that the very air you breathe is a trap, all of this is somehow immediately recognisable and locatable in the tropical and sub-tropical environment of our land.

Why do I suddenly think of Stalker when I’m asked to imagine a fictional place that tells us something about contemporary India? Perhaps, because in it you can see the endgame of where the multiple-organ failure of a society might lead.

There is a Baul song with a repeated anchoring line that goes: ajob rongey banaiyechho guru, tomar ajob karkhana—with what strange colours you have made, O Guru, this incredible factory of yours. The song, addressing the preferred deity or over-riding spirit of one’s existence, actually celebrates life, and the karkhana referred to is the factory of the human body and also possibly the cosmos itself. But positive, celebratory words can suddenly spin on their axis and pulse with opposite meanings; the awe expressed in the ajob—ajeeb in many other languages—can turn into terror. In India and the subcontinent, today we find ourselves engulfed by a series of ‘factories’, imprisoned in a net of overlapping zones, physical, mental, and in the broadest sense of the word, spiritual—an ajob karkhana created by a collective anti-Guru.

Watching Stalker today, it’s obvious that many elements of the Russia we are seeing were already in place 45 years ago; the initial programming was crude, if you will, but the basic platform for the current network of tragedies was installed by the 1970s. Similarly, it’s clear that we in India didn’t get to this hellish place by some trick of magic—there were several forks in the road, for our leaders, for us, the people, while choosing those leaders, for micro-decisions we made in the smallest arenas of family and muhalla and the macro decisions at the state and national level that we accepted when they were made on our behalf.

And yet—just as someone with adult memories of the Soviet Union may argue about Russia—India is a very different country and society from 50 years ago. Looking ahead, what the current regime has sowed over the last ten years (and, in fact, what has been sowed since Babri in 1992 and Gujarat in 2002) isn’t going to disappear any time soon. The zones of violence and division that have now become common, especially (but not only) in northern and western India, will mutate and metastise before they—one day—get flushed out of the societal system.

In the meantime, whenever anyone around me speaks wistfully about the collapse of radioactive Hindutva—something we desperately need in order to survive as a human society—I ask them to undertake an exercise: let’s say a new government comes to power, one that meets the minimum requirement of rejecting the weaponisation of religion and ethnic identity. What else do you think would change under this new regime? And what do you think would survive from these darkest of times?

At its heart, Stalker is a film about love and anti-love and how both reside in every human being. How much do you love yourself?

For instance, can we imagine a government that’s willing to interrogate and fundamentally shift the definition of economic ‘growth’ from the accumulation of ‘wealth’ at any cost to the delivery and protection of daily necessities to the poorest in the country? Can we see leaders who would be willing to dismantle the elaborate systems set in place to decimate critics and opponents? Can we see them treat the environmental meltdown as the critical emergency it is and yet as something which needs addressing on a long-term war footing? Can we imagine a central or state government putting a sharp cull on private automobile use and strictures to contain the pollution of rampant construction, or give up the gains from deforestation and mining to restore their land to Adivasis? Can we see any Indian politician in power ever reigning in the obscenely rich and taxing their wealth to raise, say, the percentage of money spent on public health and education? Can we imagine a government that will reduce the surveillance mechanisms on ordinary people, that will reduce its own immoral reach and power over ordinary lives? Can we imagine a team that is willing to hold themselves, their police, their soldiers and their staff accountable, bypassing the protections of crimes committed in the “course of duty”? The answer, of course, is that with or without the Hindutva-merchants, it is difficult to imagine a near future where political selfishness doesn’t hold sway over the often counter-intuitive, possibly unpopular ideas that would lead to greater public good.

Whether it’s a north Indian city being gassed by winter smog or a drone shot of a hyper-beautiful Xanadu-type private zoo made for a budding oligarch, whether it’s the mountain ranges of garbage you find outside Kolkata, the ugly white foam on water-bodies in Bengaluru or the ghostly emptiness of a post-pogrom muhalla in North-East Delhi, whether it’s a woman jumping onto an airline counter and screaming for a refund or the sight of opaque-eyed Rolls Royces and Lamborghinis bumping through city slums, it’s clear that we live in surreal times where fully realised dystopian spaces, crippled natural environments and ugly human actions all keep short-circuiting into each other.

In this scenario, why do I suddenly think of Stalker when I’m asked to imagine a fictional place that tells us something about contemporary India? Perhaps, because in it you can see the endgame of where the multiple-organ failure of a society might lead. And perhaps because in its unflinching vision, you find pointers to the way out.

At its heart, Stalker is a film about love and anti-love and how both reside in every human being. How much do you love yourself? At the other end of that weighing scale, how much do you love others? To be found vibrating between this love and anti-love are a person’s real, innermost desires. They need to be confronted honestly, dark and terrifying though they may be. While the zone is a very real, very vividly realised physical place, it is also a metaphor for the soul. As in a lot of Tarkovsky’s work, the film is an exploration of the individual’s relationship to themselves and to ideas and concepts of something larger than the self, whether it’s a notion of the divine or of the universe itself as a magical entity. Today, as we struggle to push back against poisonous ideas of the divine, even as we struggle to find love and sahanubhuti to navigate our very harsh realities, the film does what the very best art should–it presses sharply on our pain points and briefly manages to release them.

This article appeared as ‘Navigating the Nation Factory” in Outlook’s 30th anniversary double issue ‘ Party is Elsewhere ’ dated January 21st, 2025, which explores the subject of imagined spaces as tools of resistance and politics.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

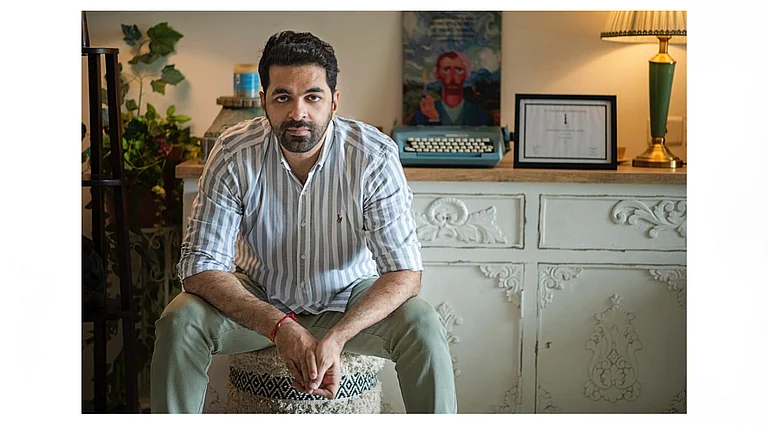

Ruchir Joshi is a writer, columnist and filmmaker based in Calcutta