In September, US started to increase its presence in the Caribbean.

US President Donald Trump saying the operation had one aim: to stop cocaine flow to the United States of America.

However, experts say, the script is familiar, and reeks of political motives

When the American military started assembling in the Caribbean in September of this year, United States President Donald Trump said the operation had just one aim: to stop the flow of cocaine before it reached the US. However, the missiles struck boats off Venezuela’s coastline, killing over 80 people in less than 30 days.

When a US aircraft carrier strike group entered the region, it became evident that this was not a policing mission against drug traffickers. It increasingly looked like a pressure campaign against Venezuela itself.

Trump has said that Venezuela is the “lynchpin” of the drug trade emanating out of Latin America.

But the US deploying naval destroyers, a missile cruiser, amphibious assault ships, MQ-9 Reaper drones, F-35 fighter jets, and the aircraft carrier USS Gerald Ford looks less like intercepting speedboats and more like a state-on-state campaign.

“First, the US destabilised Latin America on the grounds of supporting dictatorships, and destabilising democracy, and in the name of war. First, the war on communism; then, the war on corruption, waged in Brazil. Now it is war on drugs,” says R. Viswanathan, who served as the Indian Ambassador to Venezuela from 2000 to 2003.

Hari Seshasayee, a co-founder of Consilium Group and Asia-Latin America Expert for the United Nations Development Programme, says, “It is a farce to say this is a war on drugs.”

Are The US Air Strikes Off The Coast of Venezuela Crimes of War?

On September 2, 2025, US drones attacked an alleged drug boat in international waters. A second strike reportedly followed minutes later. The White House denies ordering the strike, but the international law experts are alarmed. The second strike had killed the survivors of the wreckage as well.

In any armed conflict, wounded combatants and shipwreck survivors are protected under the Geneva Conventions. Killing them is a potential war crime.

The US Congress, too, grew uneasy. The American House and Senate Armed Services Committees launched inquiries into the strikes. Even Republicans such as Rand Paul have said that the US air strikes on alleged drug boats were “outrageous.”

Fighting Narco Terrorism, or A War Without Congressional Authority?

Yet, the US continues to expand its Caribbean operations. “The US Air Force presence in the Caribbean is the largest it has ever been since the 1960s,” says Seshasayee.

The White House says it is engaged in a “non-international armed conflict” against “narco-terrorists”, transforming drug smugglers into enemy soldiers, giving Trump a cover of sorts to wage war without congressional authorisation.

“Trump learned something very early in his life, which he has deployed very often. This is that stories are often more powerful than facts, and they are more captivating than facts,” says Seshasayee, adding that the US president “makes these stories and sells them as stories,” with people “buying them because it is hard to get facts.”

Cartel de los Soles

At the centre of all this is Cartel de los Soles. Unlike the name suggests, Cartel de los Soles is a loose term used for corrupt Venezuelan officials accused of involvement in crime. By formally designating it a terrorist organisation, the US has effectively recast the Venezuelan state as a terror group—and its president, Nicolás Maduro, as a cartel boss. It is a dramatic escalation, one that transforms political hostility into a justification for lethal force.

Publicly, Washington claims the campaign is defensive—self-protection against drugs reaching American streets. Privately, the operation tells another story. Trump has personally called Maduro and urged him to resign and flee the country. When Maduro refused, Trump declared Venezuelan airspace “closed”. The US president has also authorised CIA operations inside Venezuela.

Maximum Pressure 2.0?

This is not the first time the United States has used economic or military pressure to try to dislodge the Venezuelan government. During Trump’s first term, “maximum pressure” relied heavily on sanctions and diplomatic isolation. Venezuelan oil exports were stopped. Juan Guaidó was recognised as the interim president.

Could this be the same strategy, but bolder and militarised?

Organised criminal activity is a genuine issue in the Americas, and Venezuela is indeed used as a transit route for Andean cocaine, but are missiles and carriers the most effective way to fight drug trafficking?

Seshasayee points out that, “Cocaine is produced in a very specific region where the Amazon meets the Andes, and that goes across Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Venezuela does not have the Andes mountains and the Amazon meeting in the same place. No one produces cocaine in Venezuela...and the amount that goes through it is very small.”

What is different about Venezuela is not its drugs, but its politics.

Counter productive mission objective?

Maduro’s government is known to be authoritarian and corrupt. Since taking power, the regime has exiled millions of Venezuelans and crushed any dissenting voices. But there is no evidence that Maduro personally directs drug shipments or controls prison gangs across continents. Nor is Venezuela a key player in fentanyl production.

Viswanathan points out that if regime change is the US mission, then the current tactics are counterproductive. “The Americans are driving the Maduro and his government against a wall. They are afraid of holding free and fair elections because if they do that, the next day they will all either be killed or sent to American jails,” he says.

The Rubio Factor

Within the Trump government, the person pushing for this is Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

In September, Rubio laid out the president’s brazen policy of destroying what the US believes are narcotics-laden speedboats heading from the Caribbean to the country. “Blow them up if that’s what it takes” said Rubio in fluent Spanish, referring to foreign criminal and drug-trafficking organisations during a press conference alongside the minister of foreign affairs of Ecuador in Quito. That week, the US launched the campaign of Caribbean speedboat attacks that has now claimed more than 80 lives.

“The problem is caused by Marco Rubio,” says Viswanathan, pointing out that Rubio’s family was exiled from Cuba. “The exiled Venezuelans, Cubans, and other Latin Americans are rich people, and Rubio wants to please them and prove to them that he is the hero and he could be the next president,” the former ambassador adds.

Oil Wells In Venezuela

What Venezuela does have is the world’s largest known oil reserves. While production has collapsed under sanctions and mismanagement, the prize remains more than 300 billion barrels of oil.

US firms once dominated Venezuela’s oil sector, but “the US has lost influence in Latin America and China has gained influence,” points out Seshasayee.

International Response And Latin American Memory

Internationally, the response has been lukewarm. The UK and Colombia have said they will not share intelligence on narcotics with the US. CARICOM declared the Caribbean a “zone of peace”. The leaders of Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia have publicly rejected US military intervention. CELAC, excluding the US and Canada, has made this an agenda item.

Maduro's biggest supporters, China and Russia, are, however, silent. They will not expend political capital for Venezuela's defence says Seshasayee; "They have more important things to discuss with the US President."

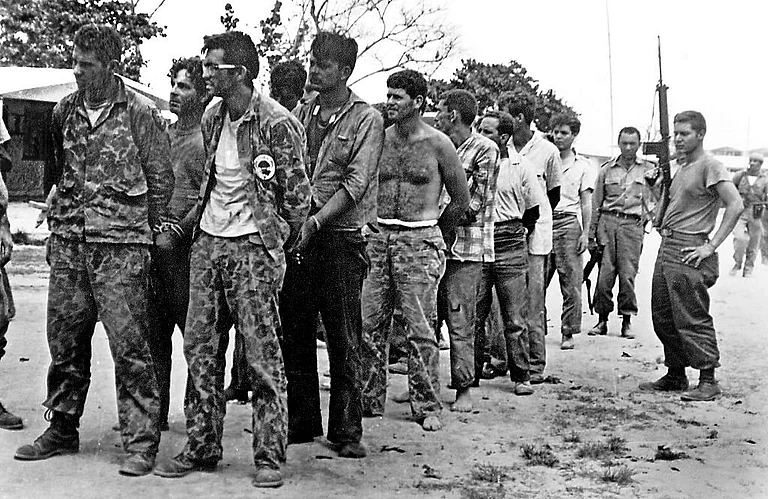

Within Latin America, there are rumblings against US actions. Latin America remembers, says Viswanathan. It has not forgotten Panama in 1989, Grenada in 1983 and the Cold War covert operations, he adds.

The danger now is escalation by accident or design. The US possesses enough firepower in the Caribbean to launch a Libya-style air campaign or targeted assassinations.

Trump has not yet declared war, but the signs are there.