Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh—formed in November 2000—mark 25 years with sharply different development outcomes, despite similar aspirations for self-governance and cultural recognition.

Mineral-rich Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh lag behind resource-poor Uttarakhand in per capita income, literacy, poverty reduction, and investment climate due to political instability, corruption, Naxalism, and weak administrative systems.

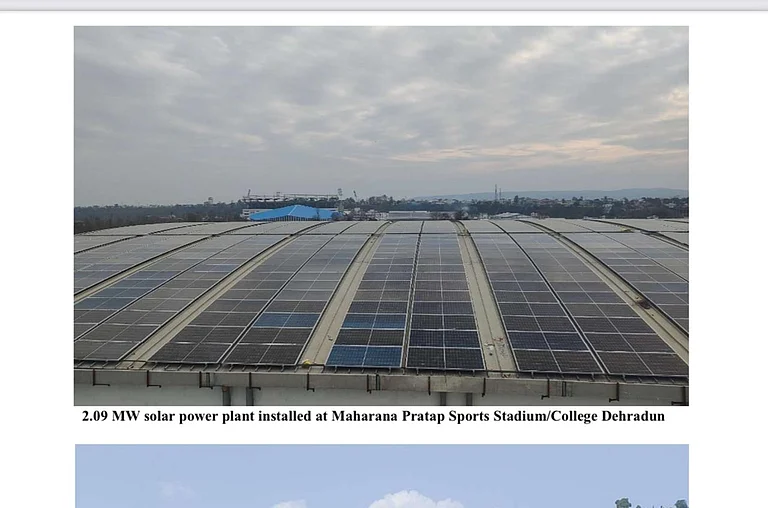

Uttarakhand’s relative success stems from stable leadership, tourism- and hydropower-driven growth, and stronger governance, though it still struggles with migration, disaster management, and widening regional inequality.

Calling November the “mother month” of new states is no exaggeration. Of India’s 35 states and union territories, 14 were born or reorganised in this month. Seven new states—including Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh—were created; three emerged through reorganisation; three became union territories; and Puducherry’s transfer to India also occurred in November. The three new states born in this month needed self-governance not only for development but also to preserve their distinct cultural identities. Geographically and culturally different from their parent states, these three are now celebrating their silver jubilee as November begins. Celebrations are essential, but self-introspection is even more critical. In these 25 years, all three have made considerable progress—Uttarakhand especially. Yet failures are no less significant. For Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in particular, the key question for reflection is: despite abundant natural resources, why have these states lagged behind Uttarakhand amid disasters and political instability?

All three were formed amid regional aspirations and equal hopes for development. Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh are both rich in minerals—Jharkhand with coal, iron, and uranium; Chhattisgarh with vast reserves of iron, bauxite, and coal. Yet, after 25 years, Uttarakhand far outpaces both on development metrics. The question remains: why have Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh fallen behind despite natural wealth? In 2024-25, Jharkhand’s per capita income stands at just ₹95,000, Chhattisgarh’s at ₹1.45 lakh, while Uttarakhand’s reaches ₹2.65 lakh—nearly double. The same trend appears in economic growth: 2023-24 GDP growth was 6.8 percent for Jharkhand, 7.9 percent for Chhattisgarh, and 8.2 percent for Uttarakhand. According to NITI Aayog’s 2023 data, 36.9 percent of Jharkhand’s population lives below the poverty line, 29.1 percent in Chhattisgarh, and only 17.2 percent in Uttarakhand. Mineral revenue in 2023 brought Jharkhand ₹28,000 crore and Chhattisgarh ₹22,000 crore. In contrast, Uttarakhand—virtually devoid of minerals—earned just ₹1,200 crore from hydropower. This disparity reveals that mineral wealth has not translated into equitable development. In literacy too, Uttarakhand leads with 88.3 percent, followed by Chhattisgarh at 77.3 percent and Jharkhand at a mere 71.4 percent. Clearly, two mineral-rich states lag economically behind one with fewer natural resources.

Jharkhand hosts giants like Coal India, SAIL, and Tata Steel. Nearly 40 percent of India’s coal and 25 percent of its iron come from here. In education and urban development, Ranchi and Jamshedpur have been developed as smart cities, home to national institutions like IIT, IIM, and AIIMS. Chhattisgarh has balanced industrial expansion with social security. The expansion of Bhilai Steel Plant and Korba’s transformation into a power hub have energised the industrial sector. Its “Chhattisgarh Model” of food security has become a national benchmark. In the Naxal-affected Bastar region, over 500 new schools have opened since 2014, and roads have tripled. The state has also earned national recognition for organic farming.

Like Uttarakhand, political instability has been Jharkhand’s biggest challenge. From 2000 to 2024, the state saw 11 chief ministers and three spells of President’s Rule. Corruption has been a major hurdle. A one-member MLA, Madhu Koda, even became chief minister, while Koda, Shibu Soren, and Hemant Soren all faced imprisonment. Jharkhand’s ₹1.86 lakh crore coal scam and Chhattisgarh’s iron ore controversies are grave indicators. Environmentally, 40 percent of Jharkhand’s forests have been impacted by mining, while deforestation in Chhattisgarh’s Hasdeo Aranya has sparked widespread protests. Chhattisgarh has been relatively stable politically, with only five chief ministers so far. Security and Naxalism persisted for years in 18 districts of Jharkhand and 10 in Chhattisgarh. Due to mining and dam projects, around 2.5 million tribals in Jharkhand and 1.8 million in Chhattisgarh have been displaced.

Uttarakhand’s development model rests on tourism, hydropower, and services—driven by stable domestic demand. In contrast, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh’s economies depend on mining, vulnerable to global demand and price volatility. Leadership stability made a difference. In Uttarakhand’s early years, experienced leader N.D. Tiwari built a robust administrative and developmental framework. Socially and administratively, Uttarakhand faces no caste conflicts or Naxal activities. Administrative efficiency varies sharply: Uttarakhand inherited a seasoned bureaucracy from Uttar Pradesh, while Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh had to build new systems from scratch. Investors prioritize safety and transparency—Uttarakhand cultivated a secure, clean image, while industries kept distance from Naxal zones.

Uttarakhand’s success is far from complete. Migration from hilly districts is a grave issue—over 1,500 villages are now deserted, and nearly 1 million youth have left seeking jobs. Disaster management remains a major challenge. The 2013 Kedarnath tragedy and 2023 Joshimath subsidence cause annual losses of around ₹5,000 crore. Governments have failed to curb corruption and hesitate to establish a Lokayukta. Economic inequality is alarming: plains districts like Haridwar earn nearly double the hilly districts like Pauri or Chamoli. Forty percent of the state’s GDP comes from just three plains districts, while ten hilly ones lag behind.

Jharkhand must channel a larger share of mineral revenue into a tribal welfare fund and strictly enforce the PESA Act to ensure at least 50 percent local employment. Chhattisgarh can strengthen its successful food security model and elevate organic farming to global prominence. For Uttarakhand, political stability, anti-corruption measures through a Lokayukta, and effective disaster management are essential.