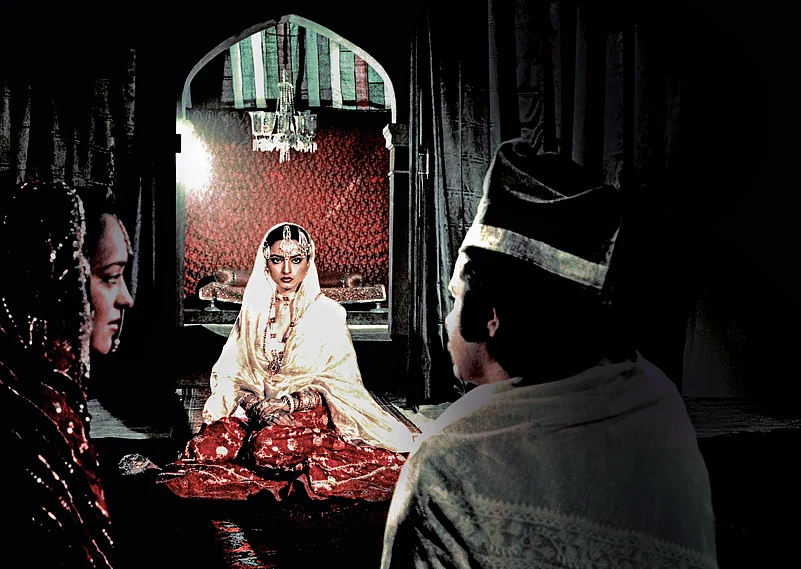

The 1981 classic Umrao Jaan, now restored in 4K, re-released in June 2025 as the labour of love and an act of cinematic remembrance, with director Muzaffar Ali himself at the helm. To witness it again is to step back into the silken hush of 19th-century Lucknow, where tehzeeb lived not just in monuments, but in music, poetry, and the unspoken eloquence of a glance. Within this world moved the tawaif—elegant and elusive, a guardian of culture, and often its silent casualty.

Timed with the film’s theatrical return, a luminous new collector’s edition book by Mapin Publishing arrives as an afterglow. Curated by director Muzaffar Ali himself and edited by Meera Ali and Sathya Saran, the volume unfurls like the film itself: layered, lyrical, and steeped in nazaakat. It is a book born of reverence—a reawakening of what was once framed in celluloid and now preserved in paper, image, ink, and memory.

Adapted from Mirza Hadi Ruswa’s novel Umrao Jan Ada (1899), the film portrays Umrao not as muse or martyr, but as a woman who dared to long. She was fluent in art, yet caged by inheritance; delicate in body, but unshaken in spirit. She craved the dignity of choice—the right to desire, to grieve, to exist. Umrao is not painted as a fallen woman nor idealised as pure. She is a figure in conflict—trained in elegance yet yearning for freedom, aware of her place yet defiant of its limitations. Her longing is not only for love, but for the liberty to name her own life. That silent rebellion becomes the soul of the film. And at the centre stands Rekha, who renders Umrao immortal. Her face, lit by Pravin Bhatt’s lens, is both veil and mirror—concealing pain, revealing truth. Every glance is deliberate, every silence weightier than words. Ali saw an internal world in her that could not be directed. Even now, she lives within the film as an artist suspended in time, still speaking to those who listen.

Across 240 pages, threaded with over 130 stunning archival visuals, the book breathes life into the unseen: anecdotes from masters, passionate essays, handwritten notes, sketches, costume designs and much more. Ali, in digitising his frames, pulls stills like verses from a ghazal, each one etched with longing. With voices like Rekha, Shabana Azmi, Rana Safvi, Kaveree Bamzai, Ira Mukhoty, Alka Pande and Suvir Saran, each essay is a golden thread in the vibrant tapestry of this collection. They write of a Lucknow now lost, the task of revering literature and of the music and mood that shaped Umrao’s world. This is not a mere companion piece. It is an ode to craft and grace, to the pauses between words, to the delicate discipline of beauty. The book memorialises Ali’s father Raja Sajid Hussain of Kotwara in the initial pages as he holds the clap board for the mahurat clap for Umrao Jaan.

In the book, Ali describes at length the inception, rationale and spirit of his film. He speaks of cinema as memory work. Umrao Jaan sought not to sentimentalise, but to hold with dignity what time wished to erase. Long before scripts or casting, it began in Lucknow’s decaying courtyards, in the rustle of sarees across stone, in the scent of old paper and attar. It began in Aligarh too—in its language, rebellion, and rhythm. Through this world, Ali found the contours of womanhood and the sting of beauty laced with loss.

Across fifteen chapters, the book meticulously compiles the world of Umrao Jaan—its making, memory, and enduring legacy four decades on. Behind it all were also craftsmen—lyricists, designers, visionaries—who have been immortalised through this text. It dwells on the textures, movement, and palette of an immortal era, capturing the film’s language of longing. From costume design to linguistic expression, the immense research and effort invested back then in creating such a visually unforgettable world is something the book is always aware of. It also explores the poster’s iconic typeface, its faithful restoration, the distribution and censor board challenges, and how bravery is always aligned with true artistry. The rare sketches and stills are evocative of a time and place cinematically conjured rather than merely constructed.

The book also highlights the musical feat of creating the nine iconic songs featured in the film with Shahryar’s words and Khayyam’s composition. The musical landscapes in these films remain inseparable from the cultural and social textures they inhabit. Ali reflects upon the Lucknowi or Awadhi classical traditions and the etiquette of mehfils. The choreography in iconic performance songs like ‘Dil Cheez Kya Hai’ is revisited as well, capturing fleeting moments of levity—cooking, playful mischief, and delicate flirtation that gently usher in Umrao’s first performance. By ‘In Aankhon Ki Masti’, she has become a name of consequence. The ghazal transforms into declaration—of command, presence, and poise—spoken through her verse, her stance, and the slow shimmer of her gaze. Rekha, too, claims a chapter for herself in the volume, where she doesn’t just play Umrao but writes poetically, truly embodying her. She reflects, with rare clarity, on the quiet labour behind forming that sacred, near-invisible thread between actor and character.

For Ali, the film’s most compelling force resides not in its form but in its emotional resonance. He thus invites readers to also visit the chapter on Umrao Jaan in his memoir, Zikr: In the Light and Shade of Time (2022) for further reading. The prologue and epilogue by Ali carry the weight of memory—tender, questioning, and reflective, almost like a quiet invocation. He recalls a Persian couplet that lingers with quiet insistence, translated to: “This heart’s doorway is not to be revealed to just anyone. Its sacred interior I will show—if only I find someone worthy.” He then gives his most precise expression for what Umrao Jaan means to him: “My Umrao is sacred. She is for aashiques, lovers. Those who emulate it will be rejected. It is sacred, and it is mine, made for the pure.” Through vivid imagery, archival fragments, and spoken memories, the book carefully weaves a textured narrative of how Umrao Jaan persists beyond the screen, in an afterlife intricately woven with music, poetry, and quiet moments.