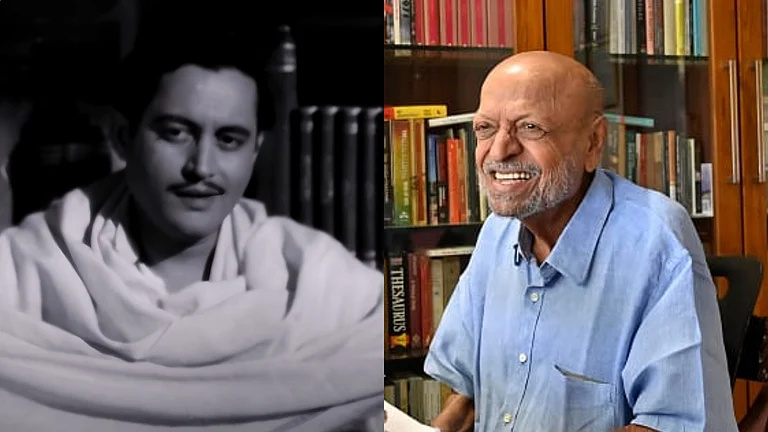

The theatrical world is mourning the loss of Ratan Thiyam, a towering figure whose life and career embodied both extraordinary artistic brilliance and complex political engagement. Passing away on 23 July 2025 at the age of 77, Thiyam’s legacy is a tapestry woven with striking visual spectacle, poetic staging, and a paradoxical relationship with the socio-political realities of his region and nation. His contributions to Indian theatre, particularly Manipuri theatre, are undeniable, yet they invite a nuanced critical discourse – one that examines the contradictions, limitations, and implications of his artistic and ideological pursuits.

Thiyam’s stature in the cultural landscape of India was formidable. As the director and chairman of prestigious institutions like the National School of Drama and the Sangeet Natak Akademi, he wielded significant influence in shaping India’s theatrical and cultural discourse. His plays, deeply rooted in Manipuri Vaishnavite idioms, became emblematic of India’s celebrated “unity in diversity.” They drew upon religious and mythological themes, employing spectacular idioms that resonated with nationalist narratives of cultural pluralism. These productions, designed for touring and international festivals, often echoed the larger Indian project of fostering cultural cohesion through shared heritage, positioning Thiyam not just as an artist but as a cultural ambassador representing India’s pluralistic identity.

However, beneath this veneer of cultural diplomacy lay a figure of profound contradictions. Thiyam’s life and work reflect a complex negotiation with tradition, politics, and regional identity. His public acts of protest – most notably, returning the Padma Shri in 2001 – highlight a man who, despite engaging in state-sponsored cultural projects, was not afraid to challenge authority. This act of defiance underscored his commitment to artistic integrity and social conscience, revealing a layered stance that transcended simplistic binaries of patriotism versus dissent. In a 2014 interview with the Times of India, Thiyam offered a striking analogy about the Northeast: “The northeast is like the gall bladder. You can get rid of it, and the body still works. It has always been treated like that.” Thiyam’s analogy likening the Northeast to a “gall bladder,” which can be discarded without affecting the body’s functioning, encapsulates his nuanced understanding of regional marginalization. It underscores how the Northeast, despite its vital contributions, is often viewed as peripheral, expendable by the political mainstream – a reality he sought to challenge through his art and activism.

Thiyam’s engagement with tradition, though rooted in regional idioms, was not immune to criticism. Some perceived his work as instrumentalized for state diplomacy, a tool to project a sanitized, harmonious image of Manipuri and Indian culture on the global stage. Critics argued that his spectacular aesthetic – characterized by intricate costumes, choreographed gestures, and symbolic set designs – sometimes veered into superficial spectacle, masking the deeper social and political contradictions within his society. This tension between form and content remains central to understanding Thiyam’s artistic legacy.

Erin B. Mee’s critique in Theatre of Roots (2008) offers a provocative perspective on this paradox. She suggests that Thiyam’s staging and political message resonate more authentically with audiences outside Manipur – particularly in Delhi and New York – while local artists and audiences in Imphal feel disconnected, perceiving his work as tailored for international spectators. Mee attributes this dissonance to India’s ‘festival culture,’ which has fostered a tendency to export Indian culture through spectacle-driven, proscenium theatre, thereby impoverishing indigenous theatrical roots. This constitutes a significant critique of India’s 'theatre of roots' project, which ostensibly aimed to engage rural India but ultimately failed to establish meaningful connections with its communities. While Mee’s observation raises important questions about the commercialization and globalized nature of Indian theatre, her critique remains underdeveloped in explaining why Thiyam’s productions continue to garner admiration despite purported superficiality.

The core issue lies in the nature of spectacle itself. Thiyam’s mastery of visual language –costumes, gestures, set designs – creates an aesthetic allure that captivates audiences and critics alike. Yet, critics and members of the Manipuri theatre fraternity have pointed out that this aesthetic often eclipses substantive engagement with the social realities of the region. His plays, despite their poetic grandeur, have been accused of lacking critical content that confronts the pain, turmoil, and contradictions of Manipuri society. The violent upheavals, identity struggles, and moral ambiguities afflicting Manipur are complex phenomena that demand theatre capable of engaging with trauma and justice, not merely beautifying it for consumption.

This critique is not merely about artistic integrity but about the social role of theatre. If art is to serve as a mirror and a critic of society, then Thiyam’s focus on spectacle risks reducing theatre to a decorative art form – an aesthetic display that, while admired, fails to provoke necessary reflection or activism. His work, in this sense, becomes a form of cultural spectacle that appeals to international audiences seeking exotic visual experiences, yet perhaps neglects the urgent need for local theatre to critically engage with the realities of violence, marginalization, and political strife.

Thiyam’s own life reflects this tension. His journey from experiencing racial stereotypes as a student at the National School of Drama in New Delhi to becoming its director exemplifies resilience and leadership. His analogy about the Northeast being like a “gall bladder” – an essential yet overlooked organ – captures his awareness of regional neglect. His art was not merely about aesthetic expression but also a political statement – an assertion of regional pride and a plea for recognition amidst systemic marginalization. His plays often carried messages of resilience, cultural pride, and regional identity, but critics argue that these messages were sometimes delivered through a lens that prioritized tradition and spectacle over critical social commentary.

The recent turmoil in Manipur, especially after May 3, 2023, underscores the urgency and relevance of Thiyam’s engagement with societal issues. Demonstrating his commitment to peace, he participated in sit-in protests, holding a poster that read “Give Beautiful Manipur for our Children,” emphasizing his hope for a safer, harmonious future for the region’s youth. This exemplified his commitment to activism and moral responsibility. Abhimanyu’s last dialogue in his play Chakravyuh (1984) – “Am I a martyr or a scapegoat?” – captures the moral ambiguity and collective suffering faced by the region’s youth amid ongoing violence. Thiyam’s life and art converge in this recognition of sacrifice, pain, and hope.

Yet, despite these efforts, Thiyam was disillusioned by political manipulations that hindered meaningful resolution. His death leaves a void in the cultural and social fabric of Manipur and India. He symbolized a potential catalyst for fostering harmony and reconciliation amidst the ongoing crisis in Manipur. His legacy – a complex interplay of tradition, spectacle, activism, and paradox – continues to provoke reflection on the role of art in society. Is theatre merely a platform for aesthetic pleasure, or does it bear the burden of confronting societal trauma? Thiyam’s life suggests the latter, but his artistic output often prioritized visual beauty over critical engagement, raising questions about the responsibilities of cultural producers.

Ratan Thiyam’s passing marks the end of an era – a moment to reflect on the paradoxes that defined his life and work. His contributions elevated Manipuri theatre to national and international prominence, yet they also exposed the limits of spectacle as a tool for social critique. Thiyam’s life and legacy compel us to consider: Can theatre be both beautiful and critical? Does spectacle serve as an effective medium for social change, or does it risk superficiality? These questions are vital as we remember a man whose art embodied contradictions – serving as a symbol of regional pride, a national icon, and a critic of authority. His death leaves us with a poignant reminder: that the true challenge of theatre lies in balancing aesthetic excellence with social responsibility, in ensuring that art does not merely adorn but also demands reflection and change. Unlike the polished images of his plays – where pain and grief were beautifully and decoratively modulated for consumption – his passing has left the people of Manipur with genuine pain and grief, a stark reminder of the profound human realities that often lie beyond the theatrical spectacle.

About The Author

Usham Rojio teaches at Visva-Bharati (a Central University established by Rabindranath Tagore), Santiniketan, West Bengal.