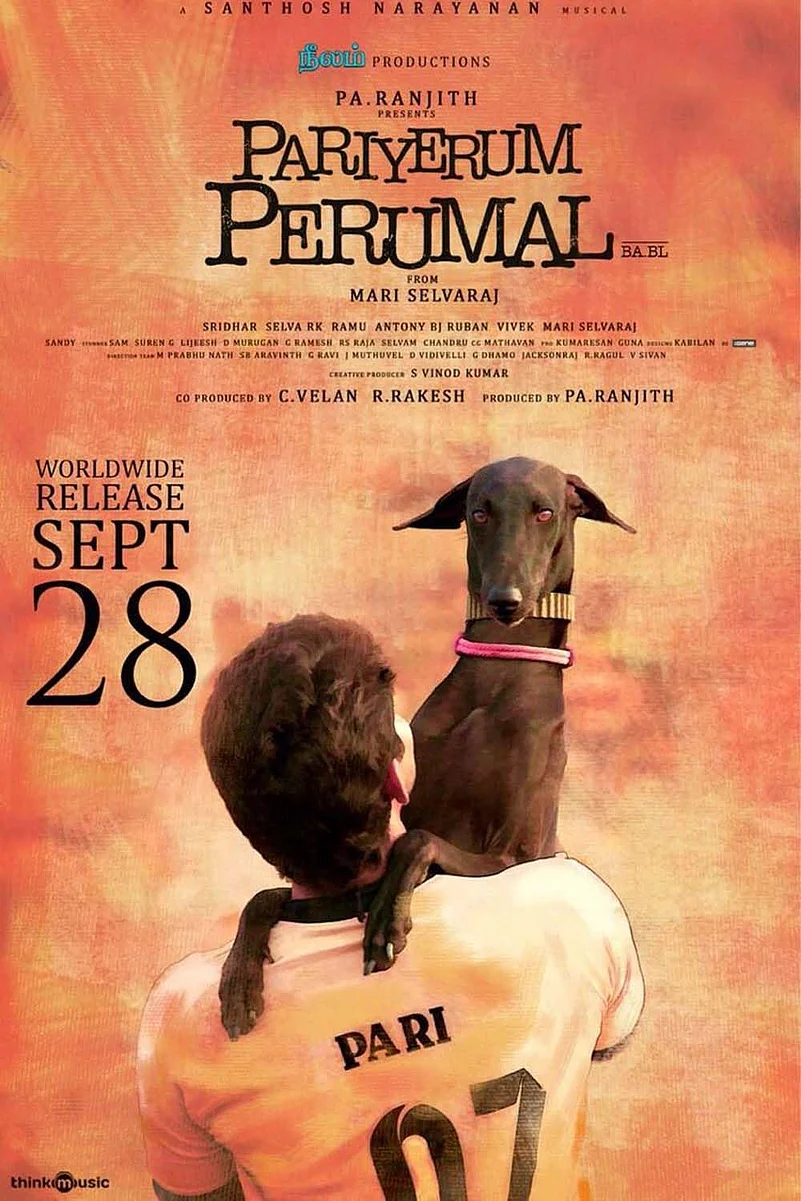

In 2018, Mari Selvaraj’s Pariyerum Perumal delivered a scathing commentary on caste-based discrimination through the story of a Dalit law student. The film lost no time in establishing its horrific truth. Our hero, Pariyerum (Kathir), aka Pariyan’s beloved pet dog Karuppi is murdered brutally by the upper castes. This is a moment of sinister caste retaliation exercised by the dominant community—a cruel, coded message meant to dehumanise Pariyan and remind him of his “place.” The dog's death is also symbolic, echoing how Dalits are routinely punished for overstepping unwritten boundaries. The horror lies not just in the act, but in its chilling normalcy, in the knowledge that taking legal recourse is not even an option. This is neither the beginning of Pariyan’s tragedies nor the end of them.

For the uninitiated, Pariyerum Perumal would have been akin to trauma porn—a story similar in ethos to It's a Wonderful Life (1946), where the protagonist simply cannot catch a break. But to those who are aware of caste-based atrocities in India—survivors, victims and allies alike—Pariyerum Perumal is closer to truth than its utilitarian, hopeful ending.

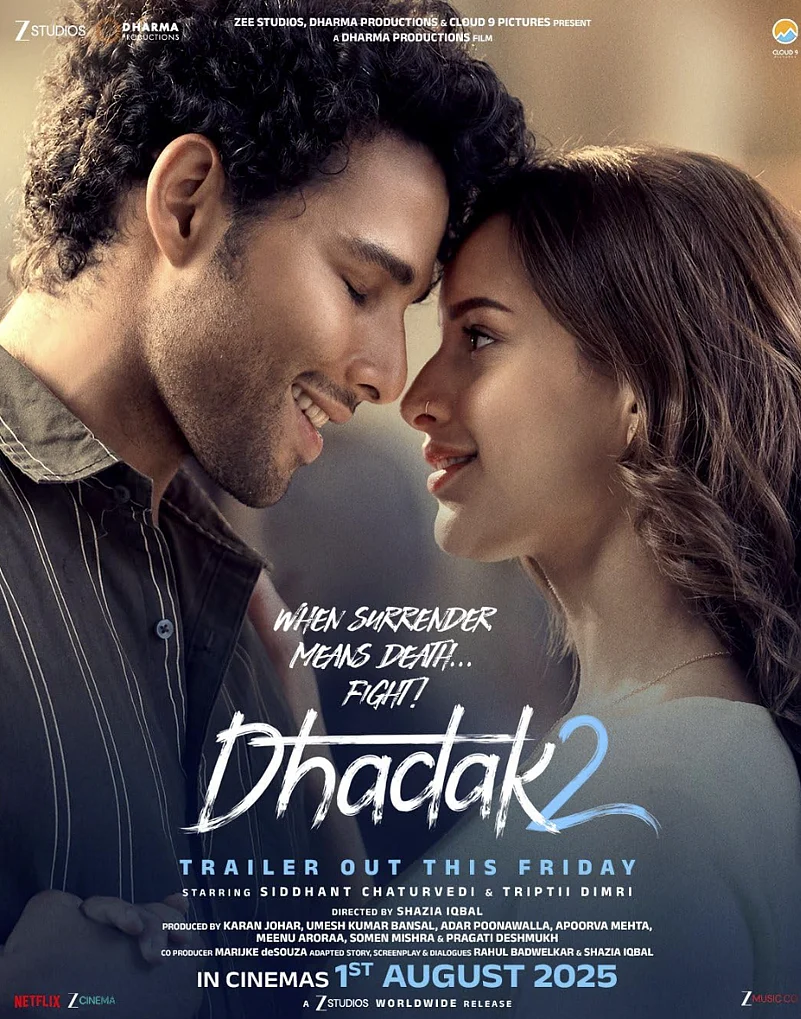

It is raw, confrontational, and deeply uncomfortable to sit with, in the way the truth about caste often is. This August, the film will be reborn in Hindi as Dhadak 2, a name that reeks more of franchise strategy than socio-political urgency. Directed by Shazia Iqbal and starring Triptii Dimri and Siddhant Chaturvedi, Dhadak 2 positions itself as a serious social drama, much like its source material. But as with Dhadak (2018), the glossy remake of Nagraj Manjule’s seminal Sairat (2016), questions loom over whether Bollywood can adapt caste-critical stories without defanging them.

I have faith in Iqbal, who has mostly worked in production design before, because of her understanding of politics. The kind of projects she has been associated with in the past—from Sacred Games (2018-2020) to Homebound (2025)—also builds confidence.

After a tense tussle with the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), Dhadak 2, which was initially slated for a November 2024 release, will finally be in theatres on August 1, 2025. But it did not survive unscathed. The CBFC, which producer Karan Johar praised for its “compassion,” has implemented a number of cuts that may have blunted the film’s caste critique.

Words like “chamar” and “bhangi” have been muted, replaced with the less specific “junglee” (of the jungle/forest), which itself has tribal connotations. Even a line that powerfully referenced “3,000 years of backlog” in systemic oppression has been diluted to a safer, “the backlog of age-old discrimination”—a less historically anchored phrase.

Entire poems, like Dalit writer Om Prakash Valmiki’s Thakur Ka Kuan (The Thakur’s Well), have been dropped. This is more than just semantics. These are acts of erasure that neutralise the historical specificity of caste discrimination, recasting it into a generic oppression narrative that doesn’t ruffle upper-caste sensibilities, not too much at least.

But this does not mean the story will lose its essence. And that is why there is still merit in championing Hindi remakes of such stories for availability to wider audiences. It is especially necessary in a country that is so deeply brainwashed into believing in the superiority and hierarchies of caste and class.

For many, the simple existence of a caste conversation in a mainstream Hindi film is progress. Director Shazia Iqbal is keenly aware of these contradictions. In an interview with Scroll, she has emphasised the importance of setting Dhadak 2 in an urban landscape, rejecting the notion that caste is a “rural issue.” She’s right. Caste discrimination has always adapted to geography—it may look different in cities, but it doesn’t disappear. In fact, it follows everywhere. As Dr. BR Ambedkar once wrote in the Annihilation of Caste (1936), “If Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem.”

By relocating the story to a tier-two urban setting, Iqbal highlights the camouflage caste wears in supposedly “modern” India.

But Can Caste Survive Brand Bollywood?

But how does one (re)tell a story as politically explosive as Pariyerum Perumal within the confines of the Hindi film industry—a space obsessed with putting marketability first, kowtowing to censorship, and the perennial need to appeal to everyone?

Its very title seems stuck in a marketing boardroom. To name it Dhadak 2 is less about narrative continuity and more about capitalising on brand recall. You don’t name a story about caste politics like you would an action or comedy franchise. Dhadak 2 is not a natural successor to Dhadak. At best, this argument will prove to be nitpicky when the film succeeds; at worst, the film will prove to be a sanitised sibling, trying to wear its revolutionary elder’s identity by stealing their clothes.

This naming is symptomatic of a deeper problem. In adapting Pariyerum Perumal, Bollywood isn’t just changing location or language; it’s changing tone, posture, and purpose. Selvaraj’s film didn’t care about mass appeal—it cared about fictionalising truth. Its rawness came from the fact that it didn’t try to universalise the Dalit experience—it showed it as specific, systemic, and painful. Its protagonist, Pariyan, is a witness, a survivor, and, crucially, a question mark aimed at the viewer.

Bollywood, however, rarely trusts its audience with discomfort.

Gender in the Shadows of Caste

If Pariyerum Perumal had one significant blind spot, it was gender. The female lead in that film is the fairest of them all (both figuratively and literally). While central to the story, she is merely treated as a narrative pawn. The romantic storyline is the catalyst, but also the weakest link in the film’s story.

Jothi Mahalakshmi (Anandhi), aka Jo, is simultaneously painfully naive and privileged. She is protected like some delicate porcelain doll by her father as well as Pariyan, but rarely treated as an agent in her own right.

Iqbal, to her credit, has recognised this flaw and chosen to deepen the character of Vidhi in Dhadak 2. Speaking of how real women are just as complex as male characters are allowed to be, she told Cinema Express, "...she's not a furniture in the film. She's a person." This is a welcome shift.

Too often, stories about caste-based love focus entirely on the male protagonist’s oppression, while ignoring the specific ways in which caste intersects with gender. Iqbal’s version already promises to broaden the scope of the original story, where none of the female protagonist’s female relatives are shown. Seemingly, she doesn’t even have a girlfriend to lean on.

A History of Dilution

Caste has always been a volatile subject for Hindi cinema. While early Hindi films like Achhut Kanya (1936), Naya Daur (1957), and Sujata (1959) touched upon caste and class with varying degrees of honesty, the liberalisation era brought with it a shift in priorities. The 1990s, as Iqbal pointed out, saw a flood of escapist love stories that actively avoided India’s social complexities.

Even in recent times, when caste has re-entered the cinematic conversation through films like Court (2014), Fandry (2013) or Santosh (2024), it’s telling that most unflinching depictions have come from outside the Bollywood system—largely from Marathi, Tamil, and Malayalam cinema. These industries have historically shown greater willingness to engage with caste as more than just a backdrop for tragic love. Even when there has been a film like Article 15 (2019) from Bollywood, it had its own saviour complex to deal with. Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan (2015) was more personal, had his lived-in experiences coded in, and dwelled in the indie frame of thought, despite its commercial release and mainstream celebration.

However, what all these films did was start a discourse. There were heated debates in the public domain on matters of caste and this seeped into the mainstream. Suddenly, we had films and shows like Bheed (2023), Dahaad (2023), Kathal-A Jackfruit Mystery (2023), the Geeli Pucchi segment in Ajeeb Daastaans (2021), and the The Heart Skipped a Beat episode on Made in Heaven (2023). These were commercial ventures that put Dalit characters front and centre. Their success also brought commercial interest to these overlooked stories. There wouldn’t be a Dhadak or Dhadak 2, if that were not the case. A Dharma would not be interested in capitalising on caste stories otherwise.

So where does Dhadak 2 fit in?

The optimist in me will argue that even a censored, diluted film that sparks conversation is better than collective, cultural ignorance. Hindi cinema does have a wider reach than most other regional cinema in India. And yes, Iqbal’s personal investment—her thoughtful articulation of caste, gender, and urbanisation—offers hope. But the realist in me knows how often Bollywood has used social issues as set dressing while maintaining the status quo.

The fact remains that a story like this needs structural honesty and it needs courage. When you remove the bite from a caste story, you don’t just make it ‘palatable’—you make it toothless. Here’s hoping Dhadak 2 is not simply selling a truth that is tailored to survive the censors and win box-office hearts; that it is ushering in a new Bollywood, which goes beyond looking to earn brownie points—for having gone there, but returning without dipping its toes fully into the well.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power